A combination of high blood pressure and decreased blood flow inside the brain may spur the buildup of harmful plaque and signal the onset of dementia, USC researchers have found.

“If you have problems with the blood vessels in the brain, then you’re going to end up with difficulty with thinking skills, cognition, memory, and ultimately this can be related to other brain pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease,” said Daniel Nation, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of psychology at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

For the study published June 1 in the journal Brain, Nation used patient data from a national medical database, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative housed at the Keck School of Medicine at USC, to explore whether constricted blood flow contributes to the buildup of amyloid plaque and, consequently, to the onset of dementia. He also determined a new way to calculate cerebrovascular resistance — a stiffening of the vessels that results from high blood pressure and low blood flow.

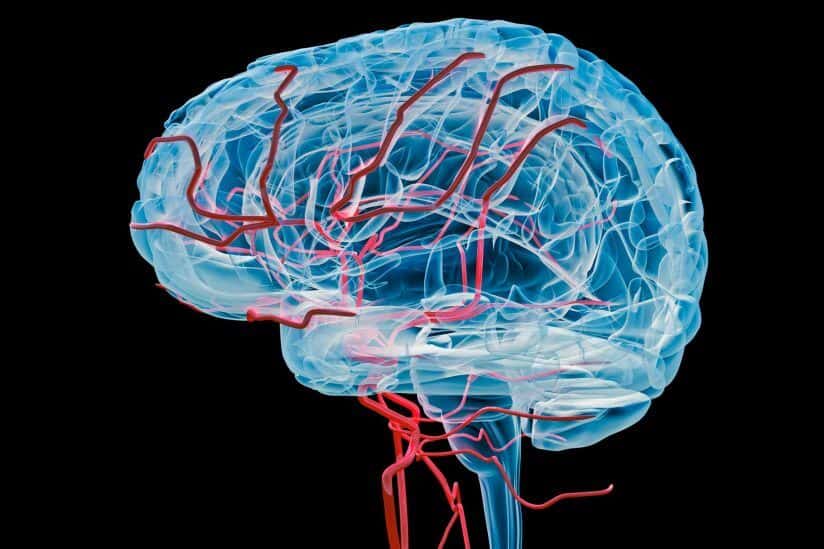

The brain’s blood vessels function as a plumbing system that delivers nutrients and oxygen to feed the brain cells and then flushes away any waste that the cells cannot use. The metabolic waste secreted by cells includes protein fragments — amyloid — that a healthy brain breaks down and expels by pulsating blood through its vessels.

The brain tightens or relaxes its vessels to maintain blood flow as it adjusts for changes in blood pressure. However, the brain vessels in Alzheimer’s patients are stiff and tight, inhibiting blood flow and enabling the sticky amyloid to accumulate, Nation found.

“The idea of cerebrovascular resistance converges on the notion that the blood vessels in Alzheimer’s brains are in this hyper-contracted state,” Nation said. “For many different reasons, the contracting blood vessels are resistant to opening up and really letting the blood in.”

Blood pressure and blood flow measures alone do not predict dementia as well as when they are examined together.

“When blood pressure goes up or down, the brain vessels accommodate so that blood flow will remain fixed,” Nation said. “So if you don’t measure blood pressure and blood flow together, then it is basically masking all of these important changes in vascular resistance, and it is very difficult to see the vessel changes that underlie this.”

Dementia and Alzheimer’s: A rising crisis

Alzheimer’s is considered one of the greatest health challenges of the century. The fifth leading cause of death for those 65 years and older, Alzheimer’s affects an estimated 5.4 million Americans — about 1 in 3 seniors, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics predicts the number of U.S. patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s will more than double to 9.1 million in the next 35 years.

As a research institution devoted to promoting lifelong health, USC has more than 70 researchers dedicated to the prevention, treatment and potential cure of Alzheimer’s disease. USC researchers across a range of disciplines are examining the health, societal and political effects and implications of the disease.

In the past decade, the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health has nearly doubled its investment in USC research. The investments include an Alzheimer Disease Research Center.

Nation’s lab at USC Dornsife is part of the multidisciplinary effort. He focuses on understanding cognitive decline associated with age-related changes in vascular structure and function. Vascular dementia is at the root of an estimated 10 percent of all Alzheimer’s cases, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

High resistance in Alzheimer’s patients

To measure resistance in the brain’s vessels, Nation developed an index that represents a ratio of average blood pressure to regional cerebral blood flow. A high index ranking for resistance indicates that amyloid is building up and that the patient is progressing toward dementia, Nation said.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative database used for the study is an extensive repository of medical data from an estimated 1,000 volunteers age 55–90. The data include results of genetic, memory and cognitive tests, brain scans and blood biomarker information.

Nation used data on three groups of volunteers: 112 men and women who did not have any amyloid buildup in their brains, 87 who did and 33 who had Alzheimer’s. The researchers controlled for characteristics including whether the people were carriers of the Alzheimer’s gene, ApoE4, which can significantly raise the risk of the disease.

Nation found that the 33 people with Alzheimer’s had lower blood flow in their brains than the people without dementia. These blood flow changes were undetectable in the earlier stages of the disease, when amyloid was accumulating, but there were no obvious signs of memory loss.

The people with Alzheimer’s also measured much higher on the cerebrovascular resistance index.

Amyloid-positive patients’ cognition worsened over time. Nation found that just two years after their initial examination, they were more likely to experience accelerated cognitive decline and progression to clinical dementia.

“Our findings suggest that change in resistance may be an early and key phenomenon in the brain that’s closely linked to the symptoms of cognitive decline in the future,” Nation said.

Treatment possibilities

In recent months, major pharmaceutical companies aiming for a cure have halted testing of Alzheimer’s drugs mid-trial due to poor results. However, recent studies point to a promising option to delay the onset of dementia or Alzheimer’s: drugs already on the market and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for other purposes.

Among the most promising are cholesterol-lowering statins — a possibility reinforced by a recent meta-data study led by USC Schaeffer Center — and blood pressure-lowering drugs known as angiotensin receptor blockers — a possibility highlighted by Nation and co-author Jean Ho in a recent study published in Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy.

Nation found that people taking blood pressure-lowering drugs have better memories than people who have elevated blood pressure and are taking other drugs. A subclass of these drugs can cross the blood-brain barrier — the filtration mechanism in the capillaries that prevents toxins from entering the brain.

Nation aims to refine how he measures vascular resistance so that he can test it in older adults in the lab. By measuring the index dynamically with brain scanners, he will track how blood pressure-lowering drugs affect vascular resistance from moment to moment in the brains of people at risk of Alzheimer’s.

Then, he said, he will work toward answering the next important question: “If we can change vascular resistance, does that change someone’s risk profile for going on to get dementia?”

USC graduate student Belinda Yew was a co-author of the cerebrovascular resistance study published in Brain. The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P50 AG005142 (an estimated $7.1 million grant that covered 10 percent of the study’s costs) and P01 AG052350 (an estimated $8.9 million grant that covered 20 percent of the study’s costs). The NIH grants also support a series of studies by Nation.

The remaining 70 percent of the study’s costs were covered by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative and a U.S. Department of Defense grant (W81XWH-12-2-0012).