If the current political discourse sounds a little like people are speaking two different languages, Penn State psychologists, who studied political rhetoric over the past three presidential elections, say that may be close to the case, semantically speaking.

In a series of studies, the researchers found a split between the same words presidential candidates from the nation’s two major political parties used and what those words mean. This semantic divide appears to be growing, they added, which may continue to make the possibility of dialogue difficult, if not impossible.

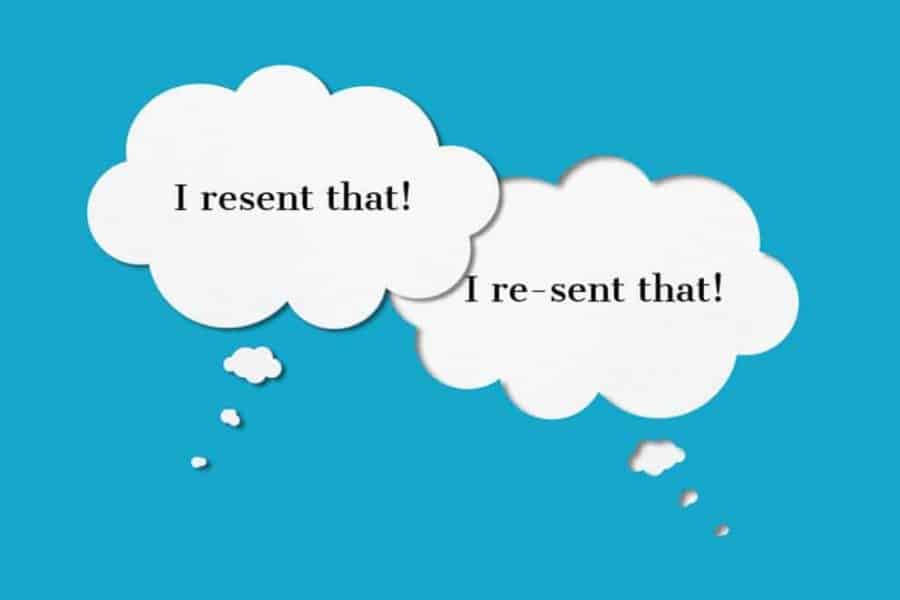

“This work was actually finished last year before the 2016 elections and we were struck by how different the rhetoric was between these different candidates,” said Ping Li, professor of psychology and associate director of the Institute for CyberScience. “In a lot of ways, it’s worse than speaking two different languages. If, for example, I speak Chinese and you don’t, you have no idea what I’m saying. But, if we’re both speaking English and you think you know what I am saying, but don’t get what I actually mean, or worse, think it means something different, it can be really confusing.”

The researchers examined how presidential candidates used words together — word association — in speeches and debates since 1999 to help determine the meaning of those words in the minds of the candidates. For example, when the word “table” appears in text together with the word “chair,” it provides meaning — or context — that the speaker is referring to a type of furniture, Li said. However, if “table” is used in a sentence with terms such as “town council” and “regulation,” for example, “table” could mean a type of legislative action.

In politics, context can be subtler and more complicated, according to the researchers, who report their findings in Behavior Research Methods, available online now.

“For example, if I use the word ‘security,’ that can mean a lot of different things,” he said. “Maybe I am referring to job security, or cyber-security, military security, or some other type of meaning for the word. Also, not only do the words in political speeches reflect different ideologies and ideas of the parties, but they can reflect the times of when the speech was made, so the meaning can change over time.”

In the most recent presidential election, the researchers said words, such as “deal” and “education,” provided not just a glimpse into how different the political rhetoric was between then-candidates Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, but also suggests differences between their beliefs.

“In Donald Trump’s speeches, as a business person, he would apply the word ‘deal’ to almost anything,” said Li, who served as the paper’s lead author. “Of course, ‘deal’ is often associated with business, but, in his speeches, he also associated it with family and education, which would not traditionally be grouped together. So, this goes back to how word association can reflect attitudes and beliefs, as also shown in a recent Science paper by Aylin Caliskan and colleagues.”

Clinton, on the other hand, would more often associate the word “education” with women and family, he said.

“In this case, ‘education’ became an issue of equality and allowing everyone access to education,” said Li, who worked with Benjamin Schloss, a graduate student in cognitive psychology, and Jake Follmer, a graduate student in educational psychology.

The researchers compiled a list of 213 single words and 397 word phrases, including 136 politically charged words — such as “minority,” “spending” and “justice” — used by American political parties. They then used an artificial neural network algorithm to statistically examine how often words appear together in a sentence, or speech.

The researchers also found that political word association has changed over time.

“We charted word meaning changes over time between parties,” said Li. “What you see is that the parties have become farther and farther apart as time goes on. In other words, for the same word, people tend to associate different words for them and, hence, convey different meanings.”

In a follow-up study, the researchers were able to examine the word associations of a group of 324 participants and, by using machine-learning algorithms, predict their political leanings and what party they belonged to, as well as which candidate they were likely to vote for in the presidential elections.

“We were able to predict voters’ reported political affiliations with a relatively high degree of accuracy simply based on the way they organized a list of 50 political concepts, that is, how they grouped these concepts,” said Li. “This also suggests the complex interdependence of language, speech and culture.”

In the future, Li said the researchers may try to provide a more detailed picture of these interdependences by looking into more political concepts and documents from a larger pool of candidates and with more sophisticated computational methods.