Do today and yesterday and tomorrow loom large in your thinking, with the more distant past and future barely visible on the horizon? That’s not unusual in today’s time-pressed world — and it seems a recipe for angst.

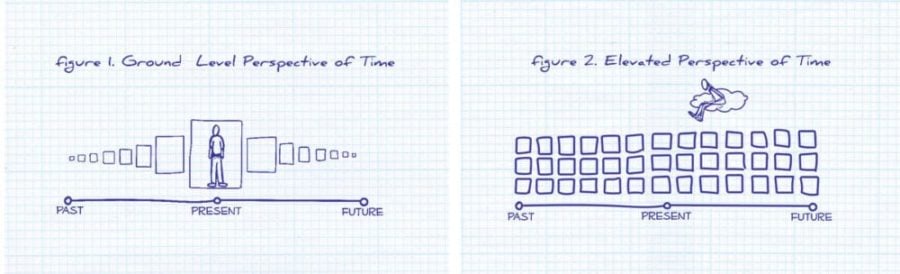

Suppose, instead, you looked down on your life, or at least your calendar, from high overhead; and all your days, future and past, were equally visible and real to you, sort of like the sketches above. Might feelings of anxiety and guilt — and other negativity — recede, as you glimpsed a broader view of all you’ve done and all you’ll have time for going forward?

That’s the notion put forward by UCLA Anderson’s Cassie Mogilner Holmes and Hal Hershfield and Stanford’s Jennifer Aaker — each of them devoted to the study of time, happiness and well-being — in a 2017 research review published in “Consumer Psychology Review.”

Despite the central roles time management and our sense of time can play in our happiness, it’s often a fraught relationship. A decision to do X today can set off pangs of guilt for not doing Y and Z. Or what we choose to do today (buy the sports car) becomes a tug-of-war with our future self, who might suggest saving more in the 401(k) instead.

Research published in 2016 by Hershfield and Mogilner Holmes, and Uri Barnea of the University of Pennsylvania, found that we also struggle to properly value time as a driver of happiness. In a series of five studies, more than six in 10 participants said that having more money would make them happier than having more time. Yet when presented with specific scenarios and asked to choose between the two, participants reported a higher level of happiness for time.

In the “Consumer Psychology Review,” Mogilner Holmes, Hershfield and Aaker raise the question of whether we might be able to smooth out the relationship — and thus give ourselves a greater nudge toward happiness — by re-engineering how we grapple with time. The paper isn’t a traditional account of a narrow research inquiry, but rather a suggestion and rough road map the authors and others might follow in further researching our perceptions of time.

The problem, as the authors see it, is that consumers as well as consumer behavior researchers tend to view time as bifurcated between the present and future (or the near future and the distant future), and all decisions are a trade-off between the two frames.

Behavioral psychology has clearly come down on the side of wanting to nudge us to focus on our future self, as it tends to prod us toward beneficial choices. For example, in a 2011 study led by Hershfield, participants presented with computer-aided renderings of their older self committed to saving more for retirement. Another study found that teenagers who were nudged to focus more on their future self than their current self were more likely to exercise. Other research led by Hershfield found that when we are more connected to our future selves we behave more ethically.

But even a well-placed focus on delayed gratification can come at a high cost. “The conflict, guilt and stress that consumers feel when forced to make trade-offs between present wants and future ideals are undesirable emotions,” write Mogilner Holmes, Hershfield and Aaker.

The authors posit that removing the wall between the two and having them “coexist” in our decision making process might reduce the emotional wear and tear of the trade-off frame.

Their theory is that we are currently held captive by a “ground-level” perspective of time, where we can only see what is within our limited field of vision: the near past and the near future. “From this vantage point, people are encased in the perceptually all-consuming present. Anything that is beyond the immediate future (or past) is not clearly visible, and is thus experienced as ’other’ and less personally relevant,” they write.

Their notion is that we might benefit from an “elevated” perspective that is able to take in the bigger picture of time, where the days and years of the future and the past have as much visibility (and thus weight) as our recent past and future. It’s a bit like using both Google Street View (see what is in your immediate vicinity) and then zooming out to take in the bigger picture map as well.

By taking a broader, elevated perspective of time, Mogilner Holmes, Hershfield and Aaker offer up some tantalizing real-world ways this approach might ease some of our time-related stress.

With an elevated view, your choices may be more aligned with what works for you in the big picture. Saying no, or saying no right now to overscheduling yourself today or this week becomes easier when you are no longer stuck down in the weeds of seeing only today and this week.

It might also reduce the guilt associated with time trade-off. For instance, a parent who is stuck in the ground-level view of time might see a day spent at work as a day not spent at home with a young child. From an elevated view, there’s the potential to see that being at work is just one element of a day or week that coexists with the time spent with a child before and after work and on weekends.

The elevated perspective might also help shift the constant challenge of whether to do something to an easier choice of when to do something. The authors turn to the classic health-conscious dilemma of staring down a tempting piece of cake. At the ground-view level, the decision is an in-the-moment choice between the indulgent “yes” and the harder trade-off of saying “no.” Move up to the elevated view of time and the decision might shift to when to eat the piece of cake, not whether you should. Maybe not today, but maybe on the weekend at the wedding, or on your designated cheat day. “This elevated perspective involves optimizing one’s weeks, rather than any given moment,” the authors write.

Mogilner Holmes, Hershfield and Aaker note that their unified theory of time has precedent in three other fields of research that have shown the value of moving past a bifurcated view of choice: emotions, relationships and financial decision making. See also: