The negative effects of social media and a hectic news cycle on our attention span has been an on-going discussion in recent years–but there’s been a lack of empirical data supporting claims of a ‘social acceleration’. A new study in Nature Communications finds that our collective attention span is indeed narrowing, and that this effect occurs – not only on social media – but also across diverse domains including books, web searches, movie popularity, and more.

Our public discussion can appear to be increasingly fragmented and accelerated. Sociologists, psychologists, and teachers have warned of an emerging crisis stemming from a ‘fear of missing out’, keeping up to date on social media, and breaking news coming at us 24/7. So far, the evidence to support these claims has only been hinted at or has been largely anecdotal. There has been an obvious lack of a strong empirical foundation.

In a new study, conducted by a team of European scientists from Technische Universität Berlin, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, University College Cork, and DTU, this empirical evidence has been presented regarding one dimension of social acceleration, namely the increasing rates of change within collective attention.

“It seems that the allocated attention in our collective minds has a certain size, but that the cultural items competing for that attention have become more densely packed. This would support the claim that it has indeed become more difficult to keep up to date on the news cycle, for example.” says Professor Sune Lehmann from DTU Compute.

The scientists have studied Twitter data from 2013 to 2016, books from Google Books going back 100 years, movie ticket sales going back 40 years, and citations of scientific publications from the last 25 years. In addition, they have gathered data from Google Trends (2010-2018), Reddit (2010-2015), and Wikipedia (2012-2017).

Rapid exhaustion of attention ressources

On this background, they find empirical evidence of ever-steeper gradients and shorter bursts of collective attention given to each cultural item. The paper uses a model for this attention economy to suggest that the accelerating vicissitudes of popular content are driven by increasing production and consumption of content, and therefore are not intrinsic to social media. This results in a more rapid exhaustion of limited attention resources.

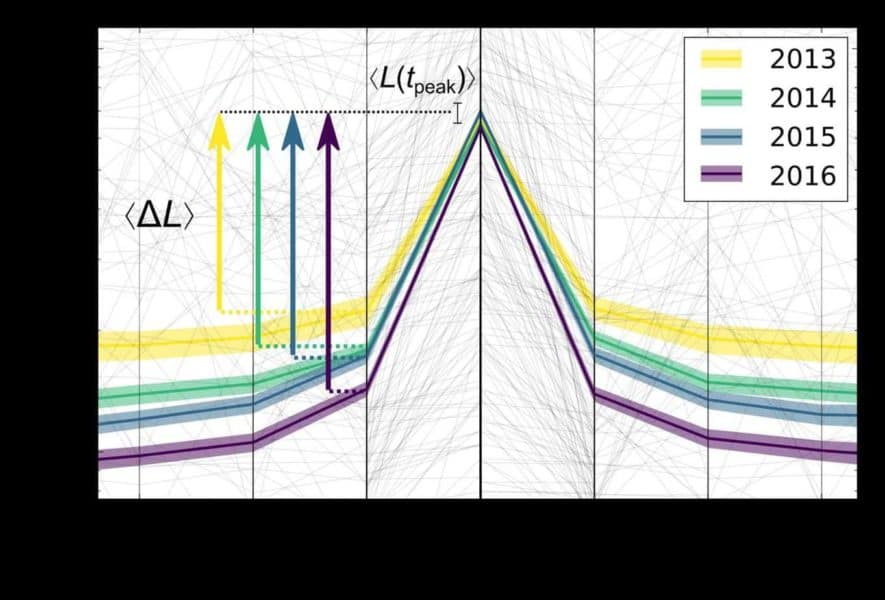

When looking into the global daily top 50 hashtags on Twitter, the scientists found that peaks became increasingly steep and frequent: In 2013 a hashtag stayed in the top 50 for an average of 17.5 hours. This gradually decreases to 11.9 hours in 2016.

This trend is mirrored when looking at other domains, online and offline–and covering different periods. Looking, for instance, at the occurrence of the same five-word phrases (n-grams) in Google Books for the past 100 years, and the success of top box office movies. The same goes for Google searches and the number of Reddit comments on individual submissions. When looking into Wikipedia and scientific publications, however, this trend was not mirrored. Though the exact reason is unclear, the authors suggest that it could be because of their being knowledge communication systems.

“We wanted to understand which mechanisms could drive this behavior. Picturing topics as species that feed on human attention, we designed a mathematical model with three basic ingredients: ‘hotness’, aging and the thirst for something new.” says Dr. Philipp Hövel, lecturer for applied mathematics, University College Cork.

This model offers an interpretation of their observations. When more content is produced in less time, it exhausts the collective attention earlier. The shortened peak of public interest for one topic is directly followed by the next topic, because of the fierce competition for novelty.

“The one parameter in the model that was key in replicating the empirical findings was the input rate – the abundance of information. The world has become increasingly well connected in the past decades. This means that content is increasing in volume, which exhausts our attention and our urge for ‘newness’ causes us to collectively switch between topics more rapidly.” says postdoc Philipp Lorenz-Spreen, Max Planck Institute for Human Development.

Since the available amount of attention remains more or less the same, the result is that people are more rapidly made aware of something happening and lose interest more quickly. However, the study does not address attention span on the level of the individual person, says Sune Lehmann:

“Our data only supports the claim that our collective attention span is narrowing. Therefore, as a next step, it would be interesting to look into how this affects individuals, since the observed developments may have negative implications for an individual’s ability to evaluate the information they consume. Acceleration increases, for example, the pressure on journalists’ ability to keep up with an ever-changing news landscape. We hope that more research in this direction will inform the way we design new communication systems, such that information quality does not suffer even when new topics appear at increasing rates.”