Teenagers who can describe their negative emotions in precise and nuanced ways are better protected against depression than their peers who can’t. That’s the conclusion of a new study about negative emotion differentiation, or NED, the ability to make fine-grained distinctions between negative emotions and apply precise labels, published in the journal Emotion.

“Adolescents who use more granular terms such as ‘I feel annoyed,’ or ‘I feel frustrated,’ or ‘I feel ashamed’—instead of simply saying ‘I feel bad’—are better protected against developing increased depressive symptoms after experiencing a stressful life event,” explains lead author Lisa Starr, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Rochester.

Those who score low on negative emotion differentiation tend to describe their feelings in more general terms such as “bad” or “upset.” As a result, they are less able to benefit from useful lessons encoded in their negative emotions, including the ability to develop coping strategies that could help them regulate how they feel.

“Emotions convey a lot of information. They communicate information about the person’s motivational state, level of arousal, emotional valence, and appraisals of the threatening experience,” says Starr. A person has to integrate all that information to figure out—“am I feeling irritated,” or “am I feeling angry, embarrassed, or some other emotion?”

Once you know that information you can use it to help determine the best course of action, explains Starr: “It’s going to help me predict how my emotional experience will unfold, and how I can best regulate these emotions to make myself feel better.”

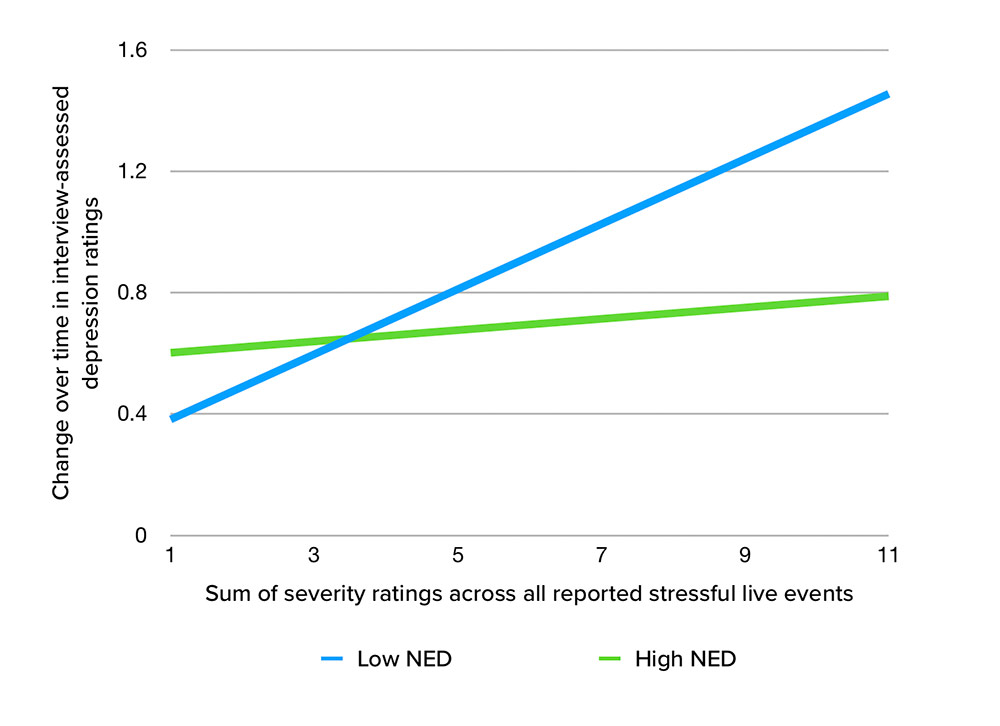

The team found that a low NED strengthens the link between stressful life events and depression, leading to reduced psychological well-being. By focusing exclusively on adolescence, which marks a time of heightened risk for depression, the study zeroed in on a gap in the research to date. Prior research suggests that during adolescence a person’s NED plunges to its lowest point, compared to that of younger children or adults. It’s exactly during this developmentally crucial time that depression rates climb steadily.

Previous research had shown that depression and low NED were related to each other, but the research designs of previous studies did not test whether a low NED temporally preceded depression. To the researchers, this phenomenon became the proverbial chicken-and-egg question: did those youth who showed signs of significant depressive symptoms have a naturally low NED, or was their NED low as a direct result of their feeling depressed?

The team, made up of Starr, Rachel Hershenberg, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Emory University, and Rochester graduate students Zoey Shaw, Irina Li, and Angela Santee, recruited 233 mid-adolescents in the greater Rochester area with an average age of nearly 16 (54 percent of them female) and conducted diagnostic interviews to evaluate the participants for depression. Next, the teenagers reported their emotions four times daily over the period of seven days. One and a half years later, the team conducted follow-up interviews with the original participants (of whom 193 returned) to study longitudinal outcomes.

The researchers found that youth who are poor at differentiating their negative emotions are more susceptible to depressive symptoms following stressful life events. Conversely, those who display high NED are better at managing the emotional and behavioral aftermath of being exposed to stress, thereby reducing the likelihood of having negative emotions escalate into a clinically significant depression over time.

Depression ranks among the most challenging public health problems worldwide. As the most prevalent mental disorder, it not only causes recurring and difficult conditions for sufferers, but also costs the U.S. economy tens of billions of dollars each year and has been identified by the World Health Organization as the number one cause of global burden among industrialized nations. Particularly depression in adolescent girls is an important area to study, note the researchers, as this age brings a surge in depression rates, with a marked gender disparity that continues well into adulthood.

Adolescent depression disrupts social and emotional development, which can lead to a host of negative outcomes, including interpersonal problems, reduced productivity, poor physical health, and substance abuse. Moreover, people who get depressed during adolescence are more likely to get repeatedly depressed throughout their life span, says Starr. That’s why mapping the emotional dynamics associated with depression is key to finding effective treatments.

“Basically you need to know the way you feel, in order to change the way you feel,” says Starr. “I believe that NED could be modifiable, and I think it’s something that could be directly addressed with treatment protocols that target NED.”

The team’s findings contribute to a growing body of research that tries to make inroads in the fight against rising rates of adolescent depression, suicidal thoughts, and suicide. According to the most recent CDC data, about 17 percent of high school students nationwide say they have thought of suicide, more than 13 percent said they actually made a suicide plan, and 7.4 percent attempted suicide in the past year.

“Our data suggests that if you are able to increase people’s NED then you should be able to buffer them against stressful experiences and the depressogenic effect of stress,” says Starr.

Funding for this study was provided by the University of Rochester. Rochester’s Irina Li was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health during the manuscript preparation.