Scientists from the University of California, Irvine School of Biological Sciences have discovered how to forestall Alzheimer’s disease in a laboratory setting, a finding that could one day help in devising targeted drugs that prevent it.

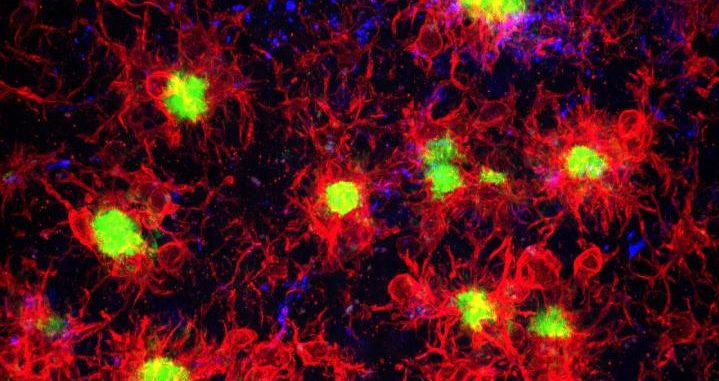

The researchers found that by removing brain immune cells known as microglia from rodent models of Alzheimer’s disease, beta-amyloid plaques – the hallmark pathology of AD – never formed. Their study will appear Aug. 21 in the journal Nature Communications.

Previous research has shown most Alzheimer’s risk genes are turned on in microglia, suggesting these cells play a role in the disease. “However, we hadn’t understood exactly what the microglia are doing and whether they are significant in the initial Alzheimer’s process,” said Kim Green, associate professor of neurobiology & behavior. “We decided to examine this issue by looking at what would happen in their absence.”

The researchers used a drug that blocks microglia signaling that is necessary for their survival. Green and his lab have previously shown that blocking this signaling effectively eliminates these immune cells from the brain. “What was striking about these studies is we found that in areas without microglia, plaques didn’t form,” Green said. “However, in places where microglia survived, plaques did develop. You don’t have Alzheimer’s without plaques, and we now know microglia are a necessary component in the development of Alzheimer’s.”

The scientists also discovered that when plaques are present, microglia perceive them as harmful and attack them. However, the attack also switches off genes in neurons needed for normal brain functioning. “This finding underlines the crucial role of these brain immune cells in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s,” said Green.

Professor Green and colleagues say their discovery holds promise for creating future drugs that prevent the disease. “We are not proposing to remove all microglia from the brain,” Professor Green said, noting the importance of microglia in regulating other brain functions. “What could be possible is devising therapeutics that affect microglia in targeted ways.”

He also believes the project’s research approach offers an avenue for better understanding other brain disorders.

“These immune cells are involved in every neurological disease and even in brain injury,” Professor Green said. “Removing microglia could enable researchers working in those areas to determine the cells’ role and whether targeting microglia could be a potential treatment.”