Certain brain tumors wire themselves into the brain’s electrical communication network, a new Stanford-led study has shown. The tumors, called high grade gliomas, form synapses with healthy neurons. The tumors receive and amplify electrical signals from the neurons to drive their own growth, according to a study published in Nature.

“Our results make it strikingly clear that this cancer is an electrically active tissue,” said postdoctoral scholar Humsa Venkatesh, PhD, the lead author of the new paper, which I wrote about for Stanford Medicine. “It was startling to see that in cancer tissue.”

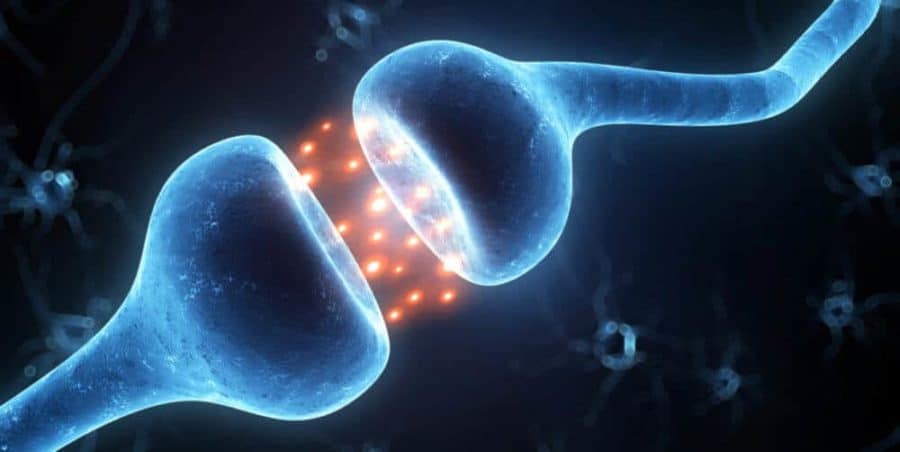

The finding is a surprise because electrical signaling is usually confined to nerves; it’s the body’s way of relaying messages quickly across long distances. The idea of cancer cells tapping into these signals is unsettling, but also opens new avenues for cancer treatment, the research team said.

“My first reaction was, ‘How horrible, it’s actually integrating into the brain,'” said pediatric neuro-oncologist Michelle Monje, MD, PhD, the senior author of the new paper. “I also thought, ‘OK, it makes sense that this type of tumor has been so hard to treat. We have to approach this disease in a very different way; it really is a disease of neuroscience, and we need to understand the electrochemical biology.'”

High-grade gliomas are a group of brain and spinal cord tumors that can occur across the lifespan and generally have a poor prognosis. Diagnoses include glioblastoma, which occurs in both children and adults, and pediatric cancers such as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma.

Using mice implanted with cells from human high-grade gliomas, the scientists conducted a series of experiments to show that structures that look like synapses exist between neurons and glioma cells, and that the synapses transmit signals into malignant cells. They also showed that tumor cells are connected to each other by a second type of cell-to-cell electrical connection called gap junctions, which amplify signals from neurons.

In mouse models, the researchers also showed that using a seizure drug to interrupt electrical signals to the tumors could slow their growth.

The findings help explain some longstanding mysteries about how high-grade gliomas affect patients. Although the cancer cells can travel throughout the body, these tumors never become established anywhere outside the brain or spinal cord. The researchers also observed hyper-excitability of healthy neurons near the tumors, which may explain why human glioma patients are prone to seizures.

“Suddenly those clear clinical realities made a lot more sense: we’re seeing this cancer structurally integrating into neural circuits,” Monje said.