To determine how melting icebergs could be affecting the ocean, a kayak-sized robot stopped the massive chunks of ice drifting and spinning in the waters of the North Atlantic—all by itself.

Or at least that’s what Hanumant Singh factored into the robot’s algorithms in order to render sharp 3D maps of icebergs in Sermilik Fjord, a 50-mile inlet into the shoreline of Eastern Greenland.

Scientists know icebergs breaking from the Greenland ice sheet are melting fast in response to climate change, but the specifics of how quickly they are melting are still unclear. Singh, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern, says the problem is figuring out how to measure large pieces of ice that are in constant motion.

“That’s very poorly understood,” he says. “The icebergs move, and they’re moving fast, some 10 kilometers a day.”

To get a concrete idea of the rate of melting, accurate measurements of the shape and surface of an iceberg need to be compared over time. But mapping an object in constant motion is a robot’s Achilles heel.

Engineers who work on autonomous drones often come up against this challenge, since robots need to scan and map their environments to move effectively and autonomously. All that is usually calculated with the assumption that things won’t move, Singh says.

“A lot of times what will happen is that you can have a robot, and it’ll map a building beautifully,” he says. “But then you have people moving, and the robot gets completely lost because it’s using static features in the environment.”

It’s no different in the water. A robot’s measurements of a moving target can be easily distorted and difficult to correct.

Singh, who engineers drone systems for remote and underwater environments, has made it his goal to get around that challenge with calculations that account for the movement of an iceberg simultaneously as the robot navigates around it and maps it. In other words, he freezes movement—with a bunch of math, really.

In a recent paper, Singh and a team of researchers describe the technology and algorithms they used to correct for the movement of a dozen icebergs floating in Sermilik Fjord.

The algorithm’s 3D reconstructions of icebergs show high-resolution details of the geometry and relief of the ice, which is sometimes impossible to capture even with raw images snapped by an ocean drone. Compared to the real life ice, the accuracy of those models is remarkably close, Singh says.

“Within a few centimeters, maybe 10,” he says.

That’s a level of detail that has been long overdue for scientists trying to determine how fast Earth’s ice is vanishing, and how that change will influence the rest of the planet.

As icebergs melt, tons of freshwater are being ushered into the sea. In the long run, such changing ocean dynamics can disrupt the way water flows and circulates around the globe, transporting essential heat and nutrients to frigid and temperate ecosystems alike.

“Our role was the mapping, but other co-authors are interested in the data,” Singh says. “They’re all physical oceanographers, and will use it to actually make models of what’s happening to the freshwater, how these icebergs are melting, and how that’s being affected by climate change.”

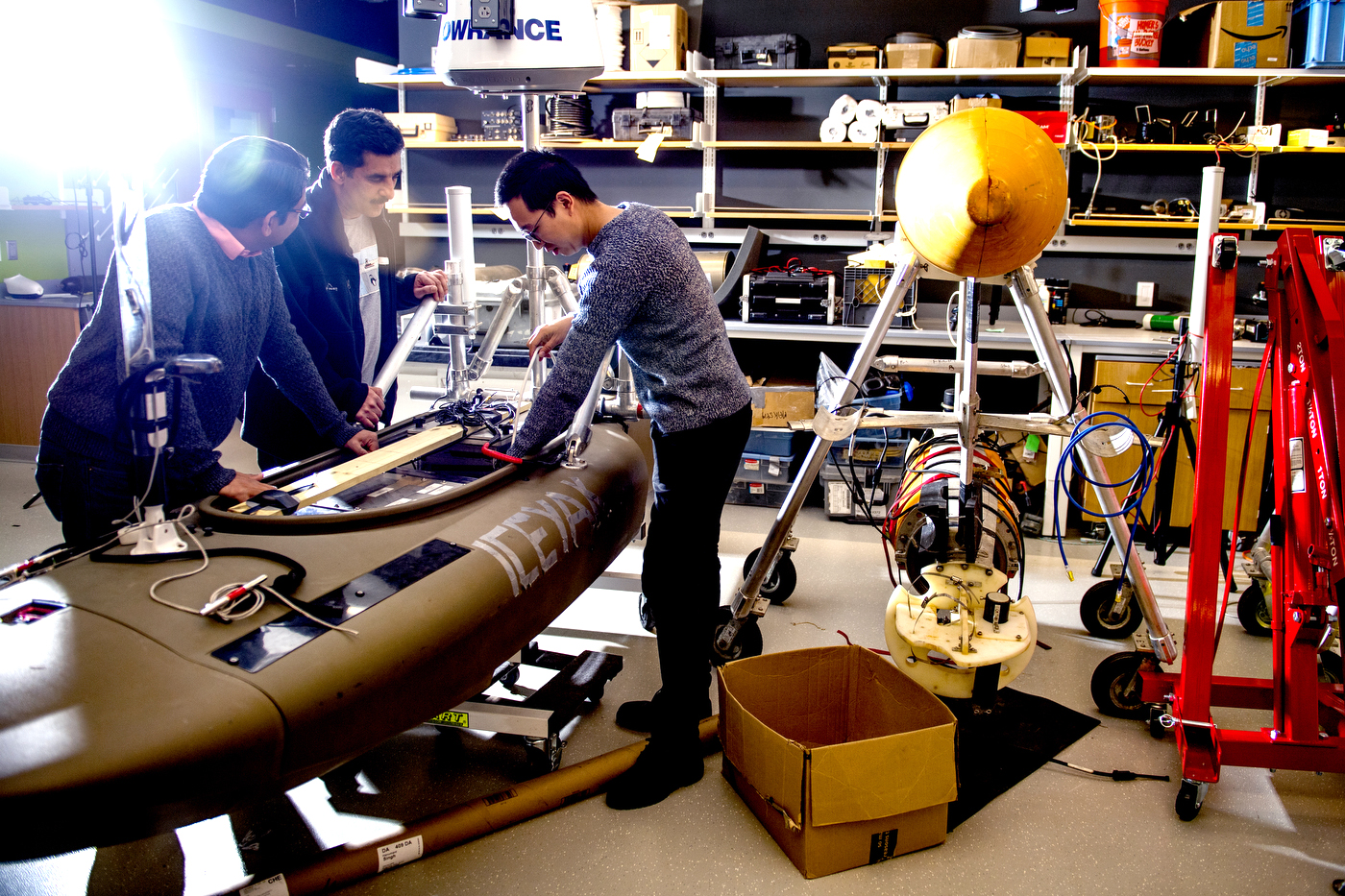

Put simply, Singh’s robotic system is just a camera and a sonar sensor mounted on a commercially available, gas-powered kayak. That’s a break from tradition, Singh says, since ocean robots tend to be expensive.

With its camera, the robot takes raw images of the part of the icebergs exposed above the water. The robot then uses those pictures to navigate strategically around the iceberg and help the sonar sensor take high-quality measurements of the submerged ice, which accounts for more than 90 percent of the ice structure.

“We get a three-dimensional shape of the whole iceberg on the top, and then we can use that as navigation to correct stuff on the bottom,” Singh says. “That data has a broad overlap, and it also gives us navigation, which allows us to correct the other sensor.”

In locations such as Greenland, lighting makes it difficult to capture images of big, shiny, and mostly white ice against a bright backdrop. That’s also a difficult environment to capture when it’s cloudy and dark: Cameras struggle to distinguish between the colors of an iceberg and the grey blends of the sky. And then there’s everything else in the field of view.

“You’re in a fjord, so you have all these sites and these pieces in the water that we want to completely ignore,” Singh says.

Not to mention how dangerous it is to be near an iceberg.

For decades, researchers have struggled to get up close and personal with icebergs. These ice formations can be several times bigger than a large parking garage, and have protruding ice above and under the water that can be dangerous if the iceberg capsizes or breaks.

That’s the whole point of using clever, but relatively cheap drones, Singh says. Robots are expendable, and they can sometimes take risks that people can’t.

“You don’t want a human being standing right next to this thing on a small boat, taking measurements,” he says. “If you’re anywhere near there, and this thing overturns, it’s going to take you with it.”

Singh says that understanding climate change is one the best things his robots can do. That includes a list of campaigns that have studied environments such as coral reefs and archeological sites underwater. Next, it could be comets and asteroids moving in the expanse of outer space.

“We’re not engineers for just engineering’s sake,” Singh says. “We also really care about bigger-picture issues, how all that works, and telling those stories to the general public. That’s what we’re about.”

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at [email protected] or 617-373-5718.