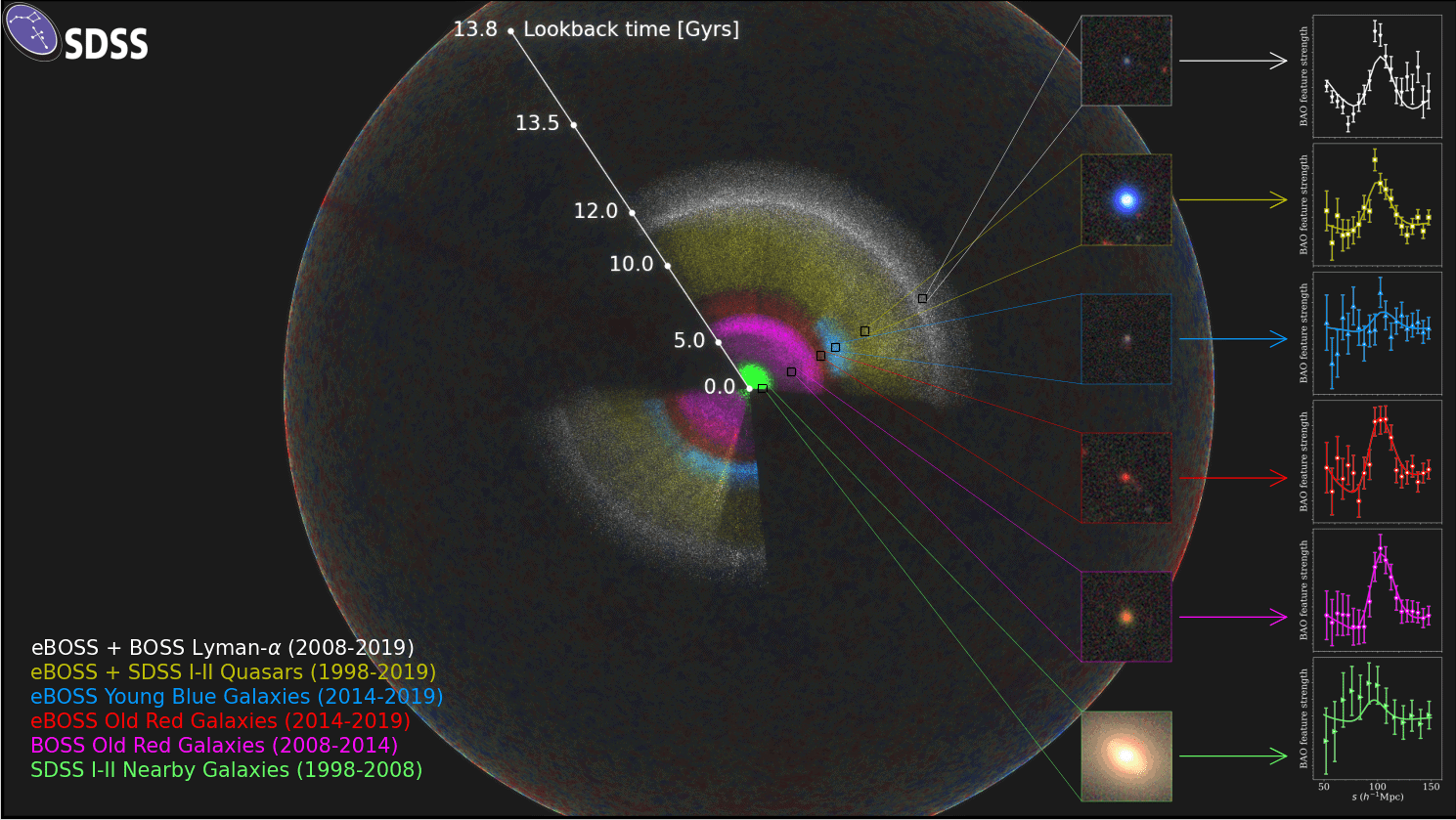

A new three-dimensional map, built after decades of collecting and analyzing data from the skies, shows how the universe has changed and expanded over an 11-billion-year period.

A new three-dimensional map, built after decades of collecting and analyzing data from the skies, shows how the universe has changed and expanded over an 11-billion-year period.

The map, published online late Sunday, is the largest 3D map of the universe ever created, and shows that about 6 billion years ago, the universe began accelerating more rapidly than it had in the 8 billion years that came before.

The map and the analyses that went into making it are the final results of an international collaboration of more than 100 astrophysicists. The work resulted in at least 23 academic papers posted late Sunday to the arXiv pre-print server, along with the map. The collaboration, called “eBOSS,” for Extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey, used quasars and faint galaxies to extend previous maps.

“One of the things we want to learn about is the time evolution of dark energy – this mysterious thing that is causing the universe to accelerate,” said Ashley Ross, the project’s catalog scientist and a lead author on one of the papers released last night. Ross is also a research scientist at The Ohio State University Center for Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics.

This survey offered new insights into how the universe expanded during a time period that had been under-studied and provides detailed measurements of more than 2 million galaxies.

Prior to eBOSS, scientists knew where objects like galaxies and quasars were in the sky as viewed from Earth – essentially a two-dimensional map of the cosmos. This survey added the distance to each object, allowing scientists to build a 3D model. This map covers more of the universe – and more time – than any map previously created.

“Ohio State scientists have made many critical contributions to the Sloan Survey over the past two decades, and it’s great to see all that hard work on instruments and analysis tools pay off in the most precise measurements ever made of the cosmic expansion history,” said David Weinberg, distinguished university professor, chair of the Ohio State astronomy department and a researcher who has worked on the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, one of the largest international attempts to map the cosmos, since just after its inception in the early 1990s.

Scientists estimate that the universe is about 13.8 billion years old. Previous studies of supernovae and galaxy maps from the Sloan Survey measured the expansion of the universe over the last 7 billion years. Other previous maps showed a snapshot of the universe about 300,000 years after the Big Bang.

That meant that cosmologists and astronomers knew the basics of how the universe expanded over the last few billion years. They also had good information about how the universe looked in the beginning because of scientific studies that assessed the elements created after the Big Bang. But until this survey, there had been a gap in that knowledge that began about 300,000 years after the universe began.

The eBOSS project mapped galaxies and quasars 7 to 11 billion light years away – meaning the light the project captured existed 7 to 11 billion years in the past. And they saw that the universe’s expansion accelerated during that time.

“This is the era when the expansion of the universe changed from slowing down to speeding up,” Weinberg said.

The eBOSS measurements confirm the picture of dark energy suggested by previous measurements, showing that it correctly predicted the cosmic expansion at these intermediate times. But they also amplify a tension with other measurements of the universe’s expansion rate today, a quantity referred to as the Hubble Constant. Scientists for years have debated the Hubble Constant’s true value. This survey showed a discrepancy in the measured expansion rates, something for which the researchers have no easy answers.

“Cosmologists are fiercely debating whether this conflict is an error in the measurements or is telling us something new about fundamental physics,” Ross said.

Ross said the results published by eBOSS on Sunday open the door for deeper analysis and more precise measurements of the universe’s expansion. A new project, called the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument – another international project in which Ohio State astronomers and physicists are deeply involved – is already underway in an attempt to collect more detailed data.

Other Ohio State researchers who contributed to or led papers released Sunday include physics graduate student Hui Kong, physics professor Klaus Honscheid and astronomy professor Paul Martini.