Materials scientists studying recharging fundamentals made an astonishing discovery that could open the door to better batteries, faster catalysts and other materials science leaps.

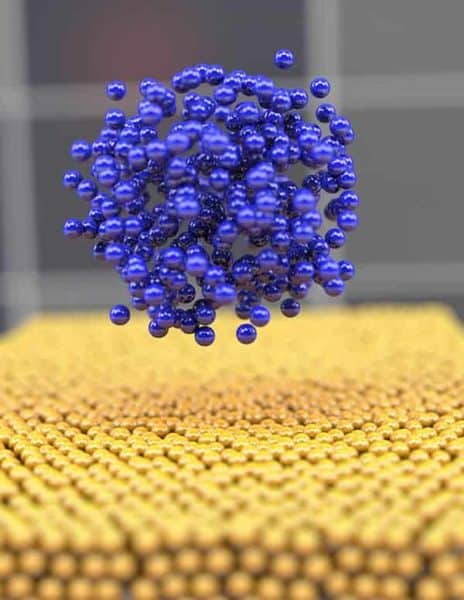

Scientists from the University of California San Diego and Idaho National Laboratory scrutinized the earliest stages of lithium recharging and learned that slow, low-energy charging causes electrodes to collect atoms in a disorganized way that improves charging behavior. This noncrystalline “glassy” lithium had never been observed, and creating such amorphous metals has traditionally been extremely difficult.

The findings suggest strategies for fine-tuning recharging approaches to boost battery life and—more intriguingly—for making glassy metals for other applications. The study was published on July 27 in Nature Materials.

Charging knowns, unknowns

Lithium metal is a preferred anode for high-energy rechargeable batteries. Yet the recharging process (depositing lithium atoms onto the anode surface) is not well understood at the atomic level. The way lithium atoms deposit onto the anode can vary from one recharge cycle to the next, leading to erratic recharging and reduced battery life.

The INL/UC San Diego team wondered whether recharging patterns were influenced by the earliest congregation of the first few atoms, a process known as nucleation.

“That initial nucleation may affect your battery performance, safety and reliability,” said Gorakh Pawar, an INL staff scientist and one of the paper’s two lead authors.

Watching lithium embryos form

The researchers combined images and analyses from a powerful electron microscope with liquid-nitrogen cooling and computer modeling. The cryo-state electron microscopy allowed them to see the creation of lithium metal “embryos,” and the computer simulations helped explain what they saw.

In particular, they discovered that certain conditions created a less structured form of lithium that was amorphous (like glass) rather than crystalline (like diamond).

“The power of cryogenic imaging to discover new phenomena in materials science is showcased in this work,” said Shirley Meng, corresponding author and researcher who led UC San Diego’s pioneering cryo-microscopy work. Meng is a professor of NanoEngineering, and Director of UC San Diego’s Sustainable Power and Energy Center, and the Institute for Materials Discovery and Design. The imaging and spectroscopic data are often convoluted, she said. “True teamwork enabled us to interpret the experimental data with confidence because the computational modeling helped decipher the complexity.”

A glassy surprise

Pure amorphous elemental metals had never been observed before now. They are extremely difficult to produce, so metal mixtures (alloys) are typically required to achieve a “glassy” configuration, which imparts powerful material properties.

During recharging, glassy lithium embryos were more likely to remain amorphous throughout growth. While studying what conditions favored glassy nucleation, the team was surprised again.

“We can make amorphous metal in very mild conditions at a very slow charging rate,” said Boryann Liaw, an INL directorate fellow and INL lead on the work. “It’s quite surprising.”

That outcome was counterintuitive because experts assumed that slow deposition rates would allow the atoms to find their way into an ordered, crystalline lithium. Yet modeling work explained how reaction kinetics drive the glassy formation. The team confirmed those findings by creating glassy forms of four more reactive metals that are attractive for battery applications.

What’s next?

The research results could help meet the goals of the Battery500 consortium, a Department of Energy initiative that funded the research. The consortium aims to develop commercially viable electric vehicle batteries with a cell level specific energy of 500 Wh/kg. Plus, this new understanding could lead to more effective metal catalysts, stronger metal coatings and other applications that could benefit from glassy metals.