Gorgonopsians were the apex predators of their day 250 million years ago. These forerunners to mammals evolved from cat-sized animals to bear-sized hunters during the middle and late Permian Period. But what made them truly formidable was their teeth.

Gorgonopsians were the first saber-toothed animals. Their canines extended up to about 5 inches and were serrated, allowing them to tear into prey the way a diner uses a steak knife to cut meat. That dental feature helped make them dominant carnivores before they went extinct. A new Harvard-led study, published Wednesday in Biology Letters, bolsters that fearsome reputation by taking a closer look at the construction of those teeth.

The research shows that the serrations were made of a complex arrangement of tissues called enamel and dentine. These tissues folded along the cutting edges of the blade-like teeth to form a series of tightly packed serrations. This type of complex tooth serration was thought to be unique to the masters of carnivory — the therapod dinosaurs, including the legendary Tyrannosaurus rex. This new analysis, however, shows dinosaurs and gorgonopsians developed this specific cutting tooth independently. Not only that, the study shows that gorgonopsians, a lineage more related to humans than dinosaurs, actually had them first.

“Our finding shows that it happened more on the mammal line as opposed to the reptile line and that it happened much earlier than we previously thought, since these animals are much older than the theropod dinosaurs,” said Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral researcher in the FAS Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. “What we’re seeing is this really cool instance of convergent evolution.”

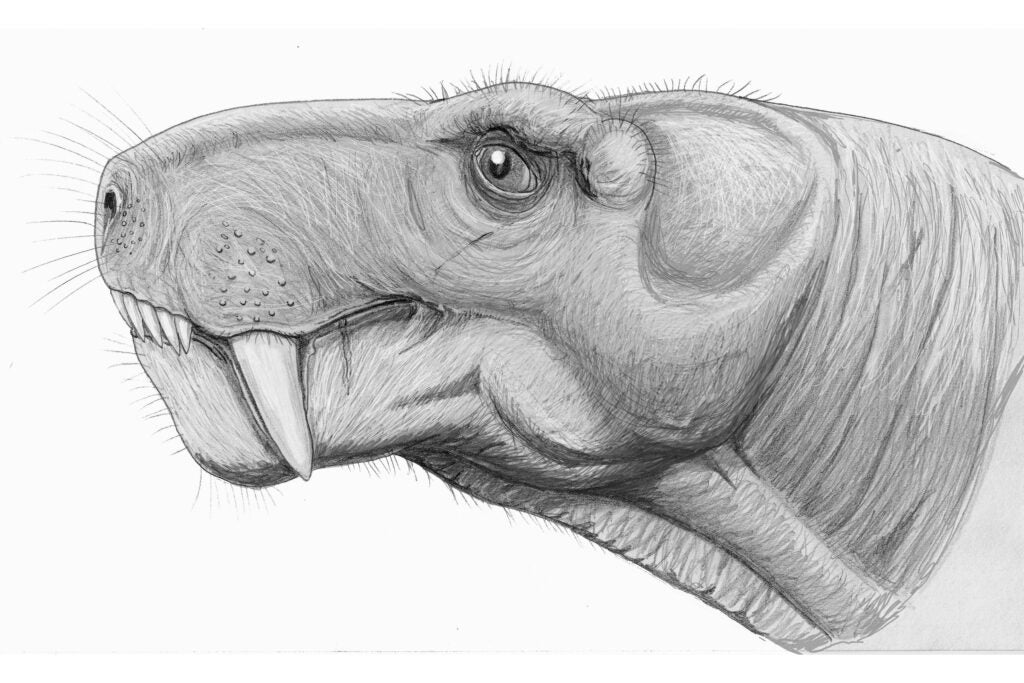

An exemplary skull of a gorgonopsian collected from Zambia in 2018 and currently at the Burke Museum of Natural History. The upper canine of this specimen is broken and would have extended below the lower jaw. Illustration of a gorgonopsid.

Photo credit: Brandon Peecook; illustration CCA 3.0/Dmitry Dogdanov

The finding is significant because of the timing and complexity involved. The fact that this happened in gorgonopsians means it occurred early in amniote evolution. Amniotes include reptiles and mammal lineages.

“It’s a very complicated way to build a serration because it involves two different tissues making really complicated folds,” Whitney said. “Typically, we associate that with time, right? The more time you have for evolution to take place, the more we think there’s the ability to evolve complicated traits. What we’re finding here is that actually these animals early in amniote evolution were able to evolve a very complicated and specialized structure.”

Whitney worked on the study with Aaron LeBlanc of King’s College in London, Ashley Reynolds from the University of Toronto, and Kirstin Brink from the University of Manitoba in Canada.

The project started because of a mistake. The group was cutting up fossilized teeth to study the tissues at the microscopic level. Working on one of the gorgonopsian canines, Whitney accidently cut through a serration. One of the co-authors examined it on a whim and realized it looked like a theropod tooth. The group thought they were onto something and decided to dive deeper.

Teeth with serrations are known as ziphodont dentitions. The team compared the ones in gorgonopsians to carnivores who also had them. The comparison group included a theropod dinosaur and other synapsids. The synapsid animals include both modern mammals and their predecessors, like the gorgonopsians.

The gorgonopsian teeth appeared similar to other synapsid teeth, but under a microscope looked more dinosaur-like. For instance, one of the comparison synapsids was Smilodon fatalis, better known as the saber-toothed tiger. While both Smilodon and gorgonopsians had saber teeth with serrations, those serrations were different and so were the way they used them. Smilodon’s serrations were made entirely of a thick enamel. This helped lead to different feeding strategies. Gorgonopsians tore flesh with their long canines, while Smilodon mainly used them to dispatch prey.

Comparing gorgonopsians with the therapod dinosaur, the scientists saw they had the same interdental folds made of enamel and dentine. This setup helps strengthen the teeth and helps them last longer in the mouth, making the animal a more efficient eater. It’s reflected in the puncture-and-pull feeding style that allowed them to cut through prey more easily.

“These animals have all evolved serrations, but the microscopic ways in which they do so may differ,” said Reynolds, a graduate student. Ultimately, it shows “there’s more than one way to skin a cat, [or in this case] a cat’s prey.”

The researchers have spent the past decade trying to understand how complex features of teeth have evolved in ancient species. While findings like this are satisfying, they believe there is a lot more to be discovered.

“It shows us that there’s a lot of complicated traits that have evolved earlier than we thought,” Whitney said. “Broadly, the group is really interested in looking at these hidden features and trying to shed light on a more complicated evolutionary history in the evolution of teeth than I think we’ve previously recognized.”

This research was supported with funding from the National Science Foundation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the National Geographic Society, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the IDP Foundation, Inc.