People with ataxia usually have progressive problems with movement, including impaired balance and coordination that affect the person’s ability to walk, talk and use fine motor skills. There are limited treatment options for this condition, and patients typically survive 15 to 20 years after symptoms first appear.

“For other conditions that also affect motor function, such as Parkinson’s disease, deep brain stimulation (DBS) has proven beneficial and is currently used to relieve motor dysfunction,” said first author Lauren Miterko, a graduate student in Dr. Roy Sillitoe’s lab at Baylor during the development of this project and currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The value of DBS in treating ataxia has not been extensively explored, so Miterko and her colleagues tested in Car8, a mouse model of hereditary ataxia, whether fine-tuning the parameters of DBS and the stimulation target location would help increase the treatment’s efficacy for the condition.

Frequency matters

“We first targeted the cerebellum, because it’s a primary motor center in the brain and this target location for DBS has seen encouraging success for treating motor problems that are associated with other conditions, such as a stroke,” Miterko said. “We systematically targeted the cerebellum with different frequencies of DBS and determined whether there was an optimal frequency that would boost the efficacy of the treatment. When we used a particular frequency, 13 Hz, that was when motor function improved in our Car8 mice.”

DBS plus exercise improved the outcomes

Neurostimulation with DBS improved muscle function and the general mobility of Car8 mice, but it seemed there was still room for improvement. The researchers then looked for additional ways to improve the condition.

“We know that exercise in general can benefit both muscle and neuronal health, and previous work in Parkinson’s disease and stroke patients mentioned that neuromodulation techniques combined with physical stimulation showed benefits, so we decided to include exercise in our investigation,” Miterko said.

We found that when the animals received DBS during exercise on a treadmill, there were improvements in motor coordination and stepping that we had not observed with DBS alone.”

“In our ataxia model, improvements did not go away after one week of treatment, which has important practical implications for potential clinical applications,” said co-author Dr. Meike E. van der Heijden, postdoctoral associate in the Sillitoe lab. “Also, all young mice with early-stage ataxia responded, suggesting that it is possible that early treatment also might provide the biggest benefit for patients in the future.”

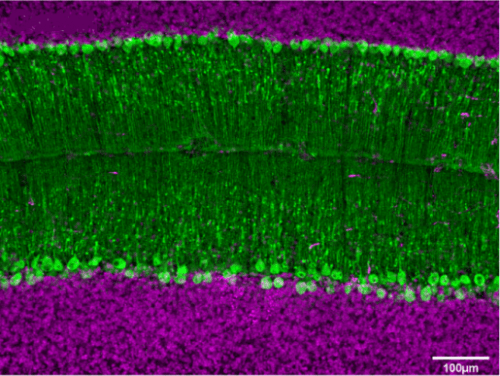

The researchers also gained insights into the type of brain cells involved in the process of restoring movement in this ataxia mouse model. They found that Purkinje cell neurotransmission is needed for DBS to be effective. Purkinje cells are a type of neuron located in the cerebellar cortex of the brain. These cells are involved in the regulation of movement, balance and coordination among other functions.

“One of our goals is to further elucidate the role Purkinje cells play in recovering from ataxia,” van der Heijden said.

“We are particularly excited about the results of this study because it may be possible to extrapolate our approach for treating not only other motor diseases, but perhaps also non-motor neuropsychiatric conditions,” said corresponding author Dr. Roy Sillitoe, associate professor of pathology and immunology and neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine, and director of the Neuropathology Core facility at the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute of Texas Children’s Hospital.

Interested in all the details of this work? Read it in the journal Nature Communications.

Other contributors to this work include Tao Lin, Joy Zhou, Jaclyn Beckinghausen and Joshua J. White, all at Baylor College of Medicine and the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital.

This work was supported by funds from Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, BCM IDDRC Grant U54HD083092 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) R01NS089664 and 1019 R01NS100874.