A new study published today in Nature Neuroscience has uncovered neuronal circuitry in the brain of rodents that may play an important role in mediating pain-induced anhedonia – a decrease in motivation to perform reward-driven behaviors. In the study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health, researchers were able to change the activity of this circuit and restore levels of motivation in a pre-clinical model of pain tested in rodents.

On a basic level, pain includes two components — sensory (the pain you feel) and affective (the negative emotional component of pain). The presence of anhedonia, a hallmark of affective pain, is a common feature of depression, and may also increase one’s vulnerability to opioid use disorder (OUD). Given this relationship, better understanding the brain circuitry involved in the affective component of pain is an important part of NIDA’s research portfolio.

“Chronic pain is experienced on many levels beyond just the physical, and this research demonstrates the biological basis of affective pain. It is a powerful reminder that psychological phenomena such as affective pain are the result of biological processes,” said NIDA Director, Nora D. Volkow, M.D. “It is exciting to see the beginnings of a path forward that may pave the way for treatment interventions that address the motivational and emotional effects of pain.”

To investigate what might be underlying the affective component of pain, researchers at Washington University in St. Louis built upon prior studies(link is external) where researchers observed that rats in pain were more likely to consume higher doses of heroin than the rats that were not in pain. In addition, their motivation for natural rewards, such as sugar tablets, was decreased. The new line of investigation sought to uncover the brain circuitry involved in this pathway, to better understand the relationship between pain and related changes in one’s motivational state.

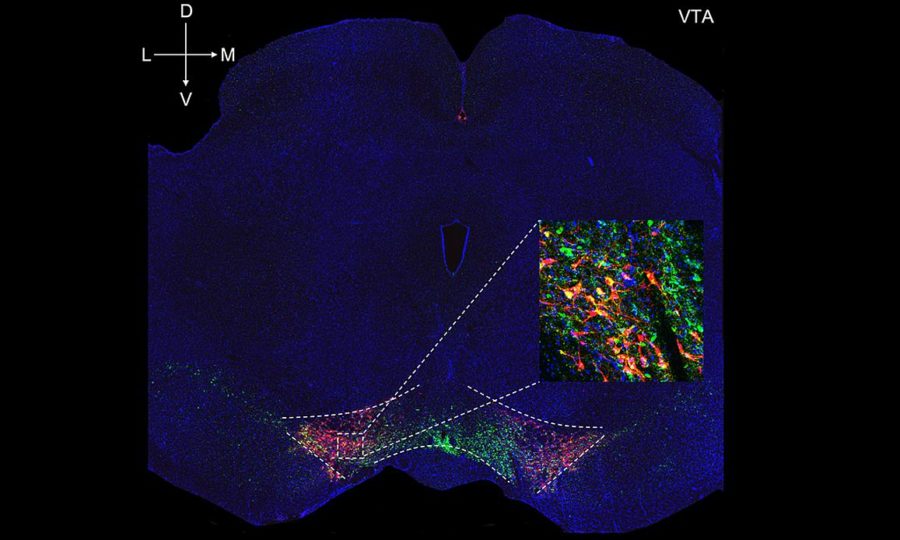

In this new study, the researchers measured the activity of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area, part of the brain’s “reward system,” which process rewards and orchestrate motivated behavior. Dopamine neuronal activity was measured in rats while they pressed a lever with their front paw to receive a sugar tablet (the reward). To assess the impact of pain on the animals’ behavior and activity of these dopamine neurons, either saline (the control condition) or a solution that produces a local inflammation (the pain condition) was injected into the hind paw.

After 48 hours, the researchers found that rats in the pain condition pressed the lever less to obtain the sugar tablet, demonstrating a decrease in motivation, and that their dopamine neurons were less active. They then discovered that the reason the dopamine neurons were less active was because pain was activating cells from a region of the brain known as the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), which makes the inhibitory neurochemical GABA, and GABA blocks the activity of the dopamine neurons.

However, when the researchers artificially restored the activity of dopamine neurons (through a process called chemogenetics), they were able to reverse the negative effect of pain on the reward system and reinstate the motivation to push the lever for the sugar tablet among the rats in pain, even with the painful stimuli still present.

In additional experiments, the researchers were also able to restore the activity of the dopamine neurons by reversing the pain-induced hyperactivity of the GABA neurons. Doing so restored the motivation of rats that were experiencing pain to prefer a sweet solution of sucrose over water, indicating an improvement in their ability to feel pleasure, despite being in pain.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time it has been reported that pain promotes increased activity of GABA neurons and an “inhibitory pathway” in the reward system of the brain from the RMTg, which causes decreased activity of dopamine cells.

“Pain has primarily been studied at peripheral sites and not in the brain, with a goal of reducing or eliminating the sensory component of pain. Meanwhile, the emotional component of pain and associated comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, and lack of ability to feel pleasure that accompany pain has been largely ignored,” said study author Jose Morón-Concepcion, Ph.D., of Washington University in St. Louis.

“It is fulfilling to be able to show pain patients that their mental health and behavioral changes are as real as the physical sensations, and we may be able to treat these changes someday,” added study author Meaghan Creed, Ph.D., of Washington University in St. Louis.