New processing methods developed by MIT researchers could help ease looming shortages of the essential metals that power everything from phones to automotive batteries, by making it easier to separate these rare metals from mining ores and recycled materials.

Selective adjustments within a chemical process called sulfidation allowed professor of metallurgy Antoine Allanore and his graduate student Caspar Stinn to successfully target and separate rare metals, such as the cobalt in a lithium-ion battery, from mixed-metal materials.

As they report in the journal Nature, their processing techniques allow the metals to remain in solid form and be separated without dissolving the material. This avoids traditional but costly liquid separation methods that require significant energy. The researchers developed processing conditions for 56 elements and tested these conditions on 15 elements.

Their sulfidation approach, they write in the paper, could reduce the capital costs of metal separation between 65 and 95 percent from mixed-metal oxides. Their selective processing could also reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 60 to 90 percent compared to traditional liquid-based separation.

“We were excited to find replacements for processes that had really high levels of water usage and greenhouse gas emissions, such as lithium-ion battery recycling, rare-earth magnet recycling, and rare-earth separation,” says Stinn. “Those are processes that make materials for sustainability applications, but the processes themselves are very unsustainable.”

The findings offer one way to alleviate a growing demand for minor metals like cobalt, lithium, and rare earth elements that are used in “clean” energy products like electric cars, solar cells, and electricity-generating windmills. According to a 2021 report by the International Energy Agency, the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has risen by 50 percent since 2010, as renewable energy technologies using these metals expand their reach.

Opportunity for selectivity

For more than a decade, the Allanore group has been studying the use of sulfide materials in developing new electrochemical routes for metal production. Sulfides are common materials, but the MIT scientists are experimenting with them under extreme conditions like very high temperatures — from 800 to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit — that are used in manufacturing plants but not in a typical university lab.

“We are looking at very well-established materials in conditions that are uncommon compared to what has been done before,” Allanore explains, “and that is why we are finding new applications or new realities.”

In the process of synthetizing high-temperature sulfide materials to support electrochemical production, Stinn says, “we learned we could be very selective and very controlled about what products we made. And it was with that understanding that we realized, ‘OK, maybe there’s an opportunity for selectivity in separation here.’”

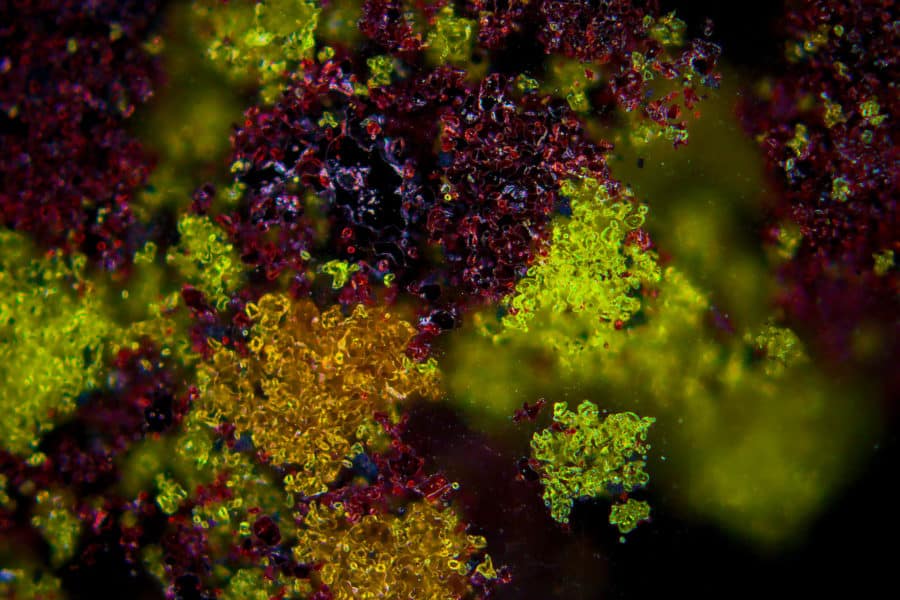

The chemical reaction exploited by the researchers reacts a material containing a mix of metal oxides to form new metal-sulfur compounds or sulfides. By altering factors like temperature, gas pressure, and the addition of carbon in the reaction process, Stinn and Allanore found that they could selectively create a variety of sulfide solids that can be physically separated by a variety of methods, including crushing the material and sorting different-sized sulfides or using magnets to separate different sulfides from one another.

Current methods of rare metal separation rely on large quantities of energy, water, acids, and organic solvents which have costly environmental impacts, says Stinn. “We are trying to use materials that are abundant, economical, and readily available for sustainable materials separation, and we have expanded that domain to now include sulfur and sulfides.”

Stinn and Allanore used selective sulfidation to separate out economically important metals like cobalt in recycled lithium-ion batteries. They also used their techniques to separate dysprosium — a rare-earth element used in applications ranging from data storage devices to optoelectronics — from rare-earth-boron magnets, or from the typical mixture of oxides available from mining minerals such as bastnaesite.

Leveraging existing technology

Metals like cobalt and rare earths are only found in small amounts in mined materials, so industries must process large volumes of material to retrieve or recycle enough of these metals to be economically viable, Allanore explains. “It’s quite clear that these processes are not efficient. Most of the emissions come from the lack of selectivity and the low concentration at which they operate.”

By eliminating the need for liquid separation and the extra steps and materials it requires to dissolve and then reprecipitate individual elements, the MIT researchers’ process significantly reduces the costs incurred and emissions produced during separation.

“One of the nice things about separating materials using sulfidation is that a lot of existing technology and process infrastructure can be leveraged,” Stinn says. “It’s new conditions and new chemistries in established reactor styles and equipment.”

The next step is to show that the process can work for large amounts of raw material — separating out 16 elements from rare-earth mining streams, for example. “Now we have shown that we can handle three or four or five of them together, but we have not yet processed an actual stream from an existing mine at a scale to match what’s required for deployment,” Allanore says.

Stinn and colleagues in the lab have built a reactor that can process about 10 kilograms of raw material per day, and the researchers are starting conversations with several corporations about the possibilities.

“We are discussing what it would take to demonstrate the performance of this approach with existing mineral and recycling streams,” Allanore says.

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. National Science Foundation.