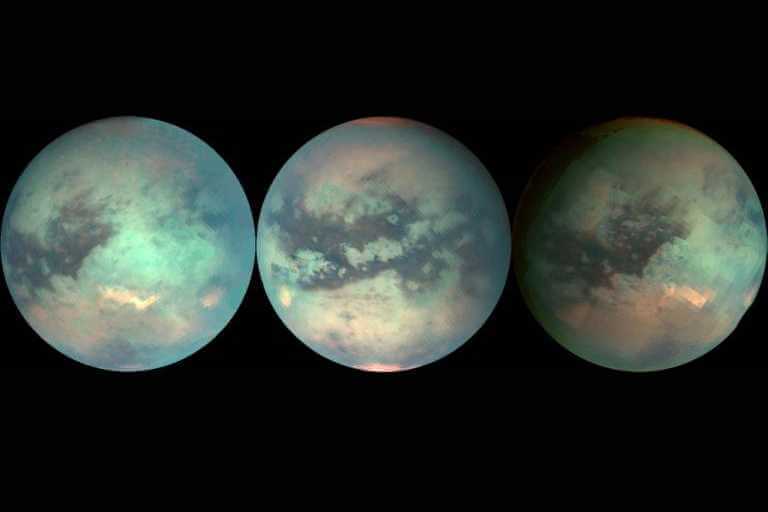

Saturn’s moon Titan looks very much like Earth from space, with rivers, lakes, and seas filled by rain tumbling through a thick atmosphere. While these landscapes may look familiar, they are composed of materials that are undoubtedly different – liquid methane streams streak Titan’s icy surface and nitrogen winds build hydrocarbon sand dunes.

The presence of these materials – whose mechanical properties are vastly different from those of silicate-based substances that make up other known sedimentary bodies in our solar system – makes Titan’s landscape formation enigmatic. By identifying a process that would allow for hydrocarbon-based substances to form sand grains or bedrock depending on how often winds blow and streams flow, Stanford University geologist Mathieu Lapôtre and his colleagues have shown how Titan’s distinct dunes, plains, and labyrinth terrains could be formed.

Titan, which is a target for space exploration because of its potential habitability, is the only other body in our solar system known to have an Earth-like, seasonal liquid transport cycle today. The new model, recently published in Geophysical Research Letters, shows how that seasonal cycle drives the movement of grains over the moon’s surface.

“Our model adds a unifying framework that allows us to understand how all of these sedimentary environments work together,” said Lapôtre, an assistant professor of geological sciences at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). “If we understand how the different pieces of the puzzle fit together and their mechanics, then we can start using the landforms left behind by those sedimentary processes to say something about the climate or the geological history of Titan – and how they could impact the prospect for life on Titan.”

A missing mechanism

In order to build a model that could simulate the formation of Titan’s distinct landscapes, Lapôtre and his colleagues first had to solve one of the biggest mysteries about sediment on the planetary body: How can its basic organic compounds – which are thought to be much more fragile than inorganic silicate grains on Earth – transform into grains that form distinct structures rather than just wearing down and blowing away as dust?

On Earth, silicate rocks and minerals on the surface erode into sediment grains over time, moving through winds and streams to be deposited in layers of sediments that eventually – with the help of pressure, groundwater, and sometimes heat – turn back into rocks. Those rocks then continue through the erosion process and the materials are recycled through Earth’s layers over geologic time.

On Titan, researchers think similar processes formed the dunes, plains, and labyrinth terrains seen from space. But unlike on Earth, Mars, and Venus, where silicate-derived rocks are the dominant geological material from which sediments are derived, Titan’s sediments are thought to be composed of solid organic compounds. Scientists haven’t been able to demonstrate how these organic compounds may grow into sediment grains that can be transported across the moon’s landscapes and over geologic time.

“As winds transport grains, the grains collide with each other and with the surface. These collisions tend to decrease grain size through time. What we were missing was the growth mechanism that could counterbalance that and enable sand grains to maintain a stable size through time,” Lapôtre said.

An alien analog

The research team found an answer by looking at sediments on Earth called ooids, which are small, spherical grains most often found in shallow tropical seas, such as around the Bahamas. Ooids form when calcium carbonate is pulled from the water column and attaches in layers around a grain, such as quartz.

What makes ooids unique is their formation through chemical precipitation, which allows ooids to grow, while the simultaneous process of erosion slows the growth as the grains are smashed into each other by waves and storms. These two competing mechanisms balance each other out through time to form a constant grain size – a process the researchers suggest could also be happening on Titan.

“We were able to resolve the paradox of why there could have been sand dunes on Titan for so long even though the materials are very weak, Lapôtre said. “We hypothesized that sintering – which involves neighboring grains fusing together into one piece – could counterbalance abrasion when winds transport the grains.”

Global landscapes

Armed with a hypothesis for sediment formation, Lapôtre and the study co-authors used existing data about Titan’s climate and the direction of wind-driven sediment transport to explain its distinct parallel bands of geological formations: dunes near the equator, plains at the mid-latitudes, and labyrinth terrains near the poles.

Atmospheric modeling and data from the Cassini mission reveal that winds are common near the equator, supporting the idea that less sintering and therefore fine sand grains could be created there – a critical component of dunes. The study authors predict a lull in sediment transport at mid-latitudes on either side of the equator, where sintering could dominate and create coarser and coarser grains, eventually turning into bedrock that makes up Titan’s plains.

Sand grains are also necessary for the formation of the moon’s labyrinth terrains near the poles. Researchers think these distinct crags could be like karsts in limestone on Earth – but on Titan, they would be collapsed features made of dissolved organic sandstones. River flow and rainstorms occur much more frequently near the poles, making sediments more likely to be transported by rivers than winds. A similar process of sintering and abrasion during river transport could provide a local supply of coarse sand grains – the source for the sandstones thought to make up labyrinth terrains.

“We’re showing that on Titan – just like on Earth and what used to be the case on Mars – we have an active sedimentary cycle that can explain the latitudinal distribution of landscapes through episodic abrasion and sintering driven by Titan’s seasons,” Lapôtre said. “It’s pretty fascinating to think about how there’s this alternative world so far out there, where things are so different, yet so similar.”

Lapôtre is also an assistant professor, by courtesy, of geophysics. Study co-authors are from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

This research was supported by a NASA Solar System Workings grant.

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

Media Contacts

Mathieu Lapôtre, School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences: (626) 232-5494, [email protected]

Danielle Torrent Tucker, School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences: (650) 497-9541, [email protected]