If you are in Bucharest and impatiently waiting for, say, your children to head off to school in the morning, you might hear yourself saying something like, “Haideţi caţi întârziat, ce mai!” Or: “Obviously, you are late!”

Uttering that sentence might not actually spur anyone into action. But in the process, it might provide interesting evidence about the way everyday language works. MIT linguist Shigeru Miyagawa contends that it does just that, in a new book exploring the function of syntax, the principles through which language is constructed.

Consider, first, that “haideţi” is a form of “hai,” a sentence particle that inflects for person and number. Here, “haideţi” is second-person plural. But one question that can be asked — Miyagawa has been asking it frequently in his recent scholarship — is why agreement is even necessary.

“It’s a real mystery as to why this system we call agreement occurs in so many human languages,” says Miyagawa, a post-tenure professor of linguistics and the Kochi-Manjiro Professor of Japanese Language and Culture at MIT. Agreement, he says, is essentially “redundant” information.

“Language is a remarkably economical system,” Miyagawa adds. “It doesn’t have extra things. But the agreement system is redundant. It repeats information to say the subject ‘Mary’ is feminine, singular, and third person. You know that just from saying, ‘Mary.’ But with the agreement system, that same information is repeated on the verb.”

The answer, Miyagawa believes, relates to a bigger issue in linguistics. Agreement is part of syntax. And syntax, Miyagawa contends, has a more expansive definition than many linguists credit it for. Rather than just being the machinery generating sentence structures, syntax also offers contextual information that can be of use to those uttering or listening to statements.

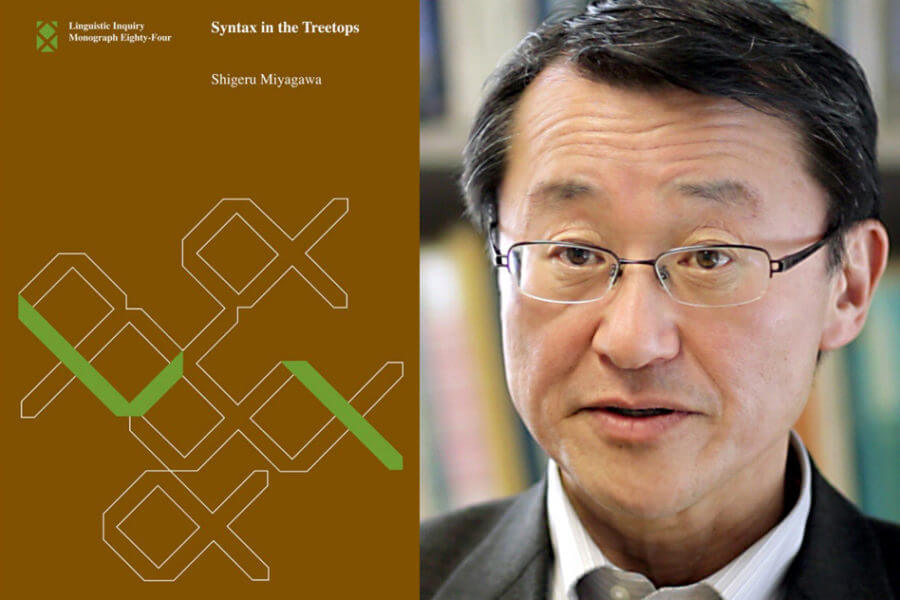

That is the main argument Miyagawa makes in the new book, “Syntax in the Treetops,” published today by the MIT Press. The book extends other research and analysis he has been conducting over the last decade about the way the way agreement signals a bigger role for syntax in common language.

“I’m extending the role of syntax, from just creating sentences to helping sentences be located in the proper discourse context, by connecting the sentence to the speaker and the addressee,” Miyagawa says.

The trilogy continues

“Syntax in the Treetops” is the third book Miyagawa has written while building his case about agreement and syntax. In his 2010 book, “Why Agree? Why Move?,” published by the MIT Press, Miyagawa made the case that agreement was more common than people realized, drawing on examples in Japanese, English, and Bantu languages. In his 2017 book, “Agreement beyond Phi,” also published by the MIT Press, Miyagawa drew on Basque and Japanese to analyze “allocutive agreement,” in which verb endings change based on the social status of the people being addressed.

In Japanese, for instance, the sentence “Hanako will come,” includes the politeness marking “mas” in a formal setting — “Hanako-ga ki-mas-u” — but not in an informal setting.

The apparent redundancy of agreement is the departure point for the argument in “Syntax in the Treetops,” which itself draws on Japanese, Basque, and Romanian, among other languages. The book’s title refers to the branching diagrams linguists use to explain sentence structures — the basic syntax.

But as Miyagawa now sees it, syntax doesn’t only involve the “lower” branches of trees but also generates high-level linguistic elements such as the “commitment phrase” of sentences — involving the speaker’s commitment to the truthfulness of the statement — and a speaker-addressee layer of language.

This is where agreement comes into the picture: A verb could exist without agreement and function just as well, in syntactical terms. But agreement provides high-level situational information, about who is speaking or listening at a given time. So, if syntax generates agreement, Miyagawa argues, it must be the case that syntax also operates in the “treetop” level communication as well.

“It turns out that syntax, which builds all these sentential structures, not only does that, but extends itself one level higher in the structure, to say, ‘Okay, I’ve got this sentence with complex structure, now I’m going to tie it to the discourse context by identifying me, the speaker, and you, the addressee,’” Miyagawa says.

Rebuilding an older case

In building this case, Miyagawa is revisiting a 1970s thesis proposed by then-MIT linguist John Ross, that every sentence has a representation of the speaker and listener in it. That claim was generally not accepted at the time, but Miyagawa believes it is worth taking seriously.

“Ross was essentially correct, but the empirical evidence he gave was not correct,” Miyagawa says. “Languages that have been so critical in the development of linguistic theory, such as those of Indo-European, don’t always reveal much about what is happening in the treetops.” He adds: “It’s really the more recent discoveries from languages like Basque, Romanian, Magahi, and Japanese, which have shown that in fact there’s something really important going on.” Miyagawa adds that even constructions in English such as the imperative can reveal insights about the treetop layer of syntax, as seen in the work of Raffaella Zanuttini of Yale University.

Other scholars find Miyagawa’s continued proposals about agreement and syntax to be worth investigating. Manfred Krifka, a linguistics scholar at Humboldt University in Berlin, has called Ross’ hypothesis in the 1970s “one of the boldest, yet most criticized, proposals in syntax.”

But in “Syntax in the Treetops,” Krifka has written, “Miyagawa presents a full and innovative picture of syntax beyond those structures that are concerned with formulating mere truth conditions, and relate to the actual use of language in communication.” As a result, he says, the hypothesis “is very much alive 50 years after it was first conceived.”

For his part, Miyagawa says he is “particularly excited” that this line of research has opened up new empirical data in this domain, such as the use of Basque and Japanese. He has also brought in data, in the book, from the language use of children with autism spectrum disorder, indicating that their deployment of language also reveals “properties of the treetop structure that are otherwise difficult to detect.” Miyagawa has begun working with autism specialists to expand this particular line of research.