Five-hundred million years ago, it was relatively safe to go back in the water. That’s because creatures of the deep had not yet evolved jaws. In a new pair of studies in eLife and Development, scientists reveal clues about the origin of this thrilling evolutionary innovation in vertebrates.

In the studies, Mathi Thiruppathy from Gage Crump’s laboratory at USC, and collaborator J. Andrew Gillis from the University of Cambridge and the Marine Biological Laboratory, looked to embryonic development as way to gain insight into evolution—an approach known as “evo-devo.”

In fishes, jaws share a common developmental origin with gills. During development, jaws and gills both arise from embryonic structures called “pharyngeal arches.” The first of these arches is called the mandibular arch because it gives rise to jaws, while additional arches develop into gills. There are also anatomical similarities: the gills are supported by upper and lower bones, which could be thought of as analogous to the upper and lower jaws.

“These developmental and anatomical observations led to the theory that the jaw evolved by modification of an ancestral gill,” said Thiruppathy, who is the eLife study’s first author and a PhD student in the Crump Lab. “While this theory has been around since the late 1800s, it remains controversial to this day.”

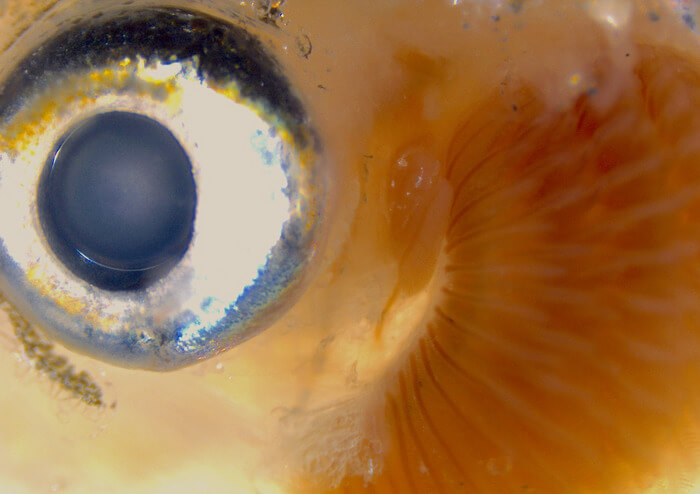

In the absence of clear fossil evidence, the eLife publication presents “living” evidence in support of the theory that jaws originated from gills. Nearly all fishes possess a tiny anatomical structure called a “pseudobranch,” which resembles a vestigial gill. However, this structure’s embryonic origin was uncertain.

Using elegant imaging and cell tracing techniques in zebrafish, Thiruppathy and her colleagues conclusively showed that the pseudobranch originates from the same mandibular arch that gives rise to the jaw. The scientists then showed that many of the same genes and regulatory mechanisms drive the development of both the pseudobranch and the gills.

In a related study just published in Development, Gillis and his Cambridge colleague Christine Hirschberger show that skates also have a mandibular arch-derived pseudobranch with genetic and developmental similarities to a gill. While zebrafish are bony fish, skates represent an entirely different evolutionary class of jawed vertebrates: cartilaginous fish.

“Our studies show that the mandibular arch contains the basic machinery to make a gill-like structure,” said Crump, the eLife study’s corresponding author, and a professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “This implies that the structures arising from the mandibular arch—the pseudobranch and the jaw—might have started out as gills that were modified over the course of deep evolutionary time.”

Gillis, who is the corresponding author of the Development study and a co-author on the eLife study, added: “Together, these two studies point to a pseudobranch being present in the last common ancestor of all jawed vertebrates. These studies provide tantalizing new evidence for the classic theory that a gill-like structure evolved into the vertebrate jaw.”

Peter Fabian, a postdoctoral trainee in the Crump Lab at USC, is also a co-author on the eLife study.

Ninety-seven percent of the support for the eLife study came from federal funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grants R35DE027550, F31DE030706, and K99DE029858). The remaining funding came from the Royal Society (RGF/EA/180087) and the University of Cambridge (14.23z).

The Development study was funded by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), The Royal Society, and the Isaac Newton Trust.