Scientists at Newcastle University have uncovered a source of oxygen that may have influenced the evolution of life before the advent of photosynthesis.

The pioneering research project, led by Newcastle University’s School of Natural and Environmental Sciences and published today in Nature Communications, uncovered a mechanism that can generate hydrogen peroxide from rocks during the movement of geological faults.

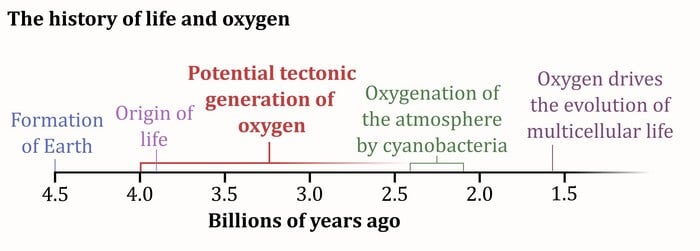

While in high concentrations hydrogen peroxide can be harmful to life, it can also provide a useful source of oxygen to microbes. This additional source of oxygen may have influenced the early evolution, and feasibly even origin, of life in hot environments on the early Earth prior to the evolution of photosynthesis.

In tectonically active regions, the movement of the Earth’s crust not only generates earthquakes but riddles the subsurface with cracks and fractures lined with highly reactive rock surfaces containing many imperfections, or defects. Water can then filter down and react with these defects on the newly fractured rock.

In the laboratory, Masters student Jordan Stone simulated these conditions by crushing granite, basalt and peridotite – rock types that would have been present in the early Earth’s crust. These were then added to water under well controlled oxygen-free conditions at varying temperatures.

The experiments demonstrated that substantial amounts of hydrogen peroxide – and as a result, potentially oxygen – was only generated at temperatures close to the boiling point of water. Importantly, the temperature of hydrogen peroxide formation overlaps the growth ranges of some of the most heat-loving microbes on Earth called hyperthermophiles, including evolutionary ancient oxygen-using microbes near the root of the Universal Tree of Life.

Lead author Jordan Stone, who conducted this research as part of his MRes in Environmental Geoscience, said: “While previous research has suggested that small amounts of hydrogen peroxide and other oxidants can be formed by stressing or crushing of rocks in the absence of oxygen, this is the first study to show the vital importance of hot temperatures in maximising hydrogen peroxide generation.”

Principal Investigator Dr Jon Telling, Senior Lecturer, added: “This research shows that defects on crushed rock and minerals can behave very differently to how you would expect more ‘perfect’ mineral surfaces to react. All these mechanochemical reactions need to generate hydrogen peroxide, and therefore oxygen, is water, crushed rocks, and high temperatures, which were all present on the early Earth before the evolution of photosynthesis and which could have influenced the chemistry and microbiology in hot, seismically active regions where life may have first evolved.”

The work was supported through grants from the Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC) and the UK Space Agency. A major new follow-up project led by Dr Jon Telling, funded by NERC, is underway to determine the significance of this mechanism for supporting life in the Earth’s subsurface.