A new model developed by Caltech and JPL researchers suggests that Antarctica’s ice shelves may be melting at an accelerated rate, which could eventually contribute to more rapid sea level rise. The model accounts for an often-overlooked narrow ocean current along the Antarctic coast and simulates how rapidly flowing freshwater, melted from the ice shelves, can trap dense warm ocean water at the base of the ice, causing it to warm and melt even more.

The study was conducted in the laboratory of Andy Thompson, professor of environmental science and engineering, and appears in the journal Science Advances on August 12.

Ice shelves are outcroppings of the Antarctic ice sheet, found where the ice juts out from land and floats on top of the ocean. The shelves, which are each several hundred meters thick, act as a protective buffer for the mainland ice, keeping the whole ice sheet from flowing into the ocean (which would dramatically raise global sea levels). However, a warming atmosphere and warming oceans caused by climate change are increasing the speed at which these ice shelves are melting, threatening their ability to hold back the flow of the ice sheet into the ocean.

“If this mechanism that we’ve been studying is active in the real world, it may mean that ice shelf melt rates are 20 to 40 percent higher than the predictions in global climate models, which typically cannot simulate these strong currents near the Antarctic coast,” Thompson says.

In this study, led by senior research scientist Mar Flexas, the researchers focused on one area of Antarctica: the West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP). Antarctica is roughly shaped like a disk, except where the WAP protrudes out of the high polar latitudes and into lower, warmer latitudes. It is here that Antarctica sees the most dramatic changes due to climate change. The team has previously deployed autonomous vehicles in this region, and scientists have used data from instrumented elephant seals to measure temperature and salinity in the water and ice.

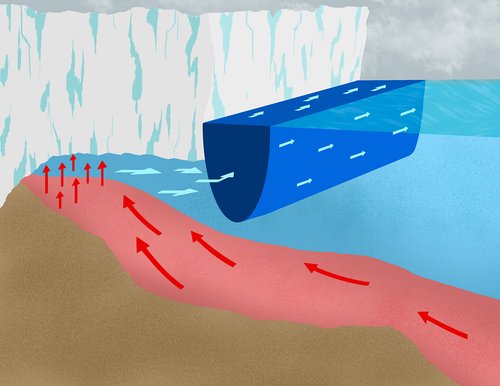

The team’s model takes into account the narrow Antarctic Coastal Current that runs counterclockwise around the entire Antarctic continent, a current which many climate models do not include because it is so small.

“Large global climate models don’t include this coastal current, because it’s very narrow—only about 20 kilometers wide, while most climate models only capture currents that are 100 kilometers across or larger,” Flexas explains. “So, there is a potential for those models to not represent future melt rates very accurately.”

The model illustrates how freshwater that melts from ice at the WAP is carried by the coastal current and transported around the continent. The less-dense freshwater moves along quickly near the surface of the ocean and traps relatively warm ocean saltwater against the underside of the ice shelves. This then causes the ice shelves to melt from below. In this way, increased meltwater at the WAP can propagate climate warming via the Coastal Current, which in turn can also escalate melting even at West Antarctic ice shelves thousands of kilometers away from the peninsula. This remote warming mechanism may be part of the reason that the loss of volume from West Antarctic ice shelves has accelerated in recent decades.