We often think that our world is an infinite realm comprising great plains, jungles and oceans, teeming with wild animals featured in memorable nature shows like the BBC’s Planet Earth. But the first global census of wild mammal biomass, conducted by Weizmann Institute of Science researchers and reported today in PNAS, reveals the extent to which our natural world – along with its most iconic animals – is a vanishing one.

The new report shows that the biomass of wild mammals on land and at sea is dwarfed by the combined weight of cattle, pigs, sheep and other domesticated mammals. A team headed by Prof. Ron Milo found that the biomass of livestock has reached about 630 million tonnes – 30 times the weight of all wild terrestrial mammals (approximately 20 million tonnes) and 15 times that of wild marine mammals (40 million tonnes).

An earlier, widely-discussed study by researchers in Milo’s lab in Weizmann’s Plant and Environmental Sciences Department showed that in 2020, the mass of human-made objects – anything from skyscrapers to newspapers – had surpassed the planet’s entire biomass, from redwood trees to honeybees. In the latest study, the researchers offer a new perspective on humanity’s rapidly increasing impact on our planet, seen in the ratio between humans and domesticated mammals, and wild mammals.

“This study is an attempt to see the bigger picture,” says Milo. “The dazzling diversity of various mammal species may obscure the dramatic changes affecting our planet. But the global distribution of biomass reveals quantifiable evidence of a reality that can be difficult to grasp otherwise: It lays bare the dominance of humanity and its livestock over the far smaller populations of remaining wild mammals.”

To calculate the biomass of our warm-blooded class, the researchers collected existing censuses of wild mammal species and the defining characteristics of hundreds more. Research students Lior Greenspoon and Eyal Krieger led the study’s translation of the accumulated information into biomass estimates. The collected censuses yielded data on about half of the global biomass of mammals. The team calculated the remaining half using a machine-learning computational model that had been trained on the initial half and that incorporated multiple parameters, including individuals’ body weight, area distribution, nutrition and zoological classification.

The analysis showed that human influence also strongly affects the relatively limited remaining mammalian presence in nature. Many of the wild mammals at the top of the biomass chart, such as the white-tailed deer and wild boar species, got there partly owing to human activity and are now seen as pests in some areas.

The new study’s estimates of biomass ratios may help to monitor wild mammal populations globally and to assist in evaluating the risk posed by diseases that spread from animals to humans – a dynamic that many epidemiologists warn will continue to generate epidemics.

Six lbs per person

For humanity, wild mammals are an inspiration, and they often serve as icons encouraging nature conservation efforts. To better understand human impact on the environment, scientists in Milo’s lab are currently analyzing how mammalian biomass has changed over the past century. “I find it important to understand, for example, when exactly the combined weight of domesticated mammals surpassed that of wild ones,” says Greenspoon. “A better understanding of the human-induced changes can help set conservation goals and afford us perspective on long-term global processes.”

“The more we’re exposed to nature’s full splendor, be it through films, museums or eco-tourism, the more we might be tempted to imagine that nature is an endless and inexhaustible resource. In reality, the weight of all remaining wild land mammals is less than 10 percent of humanity’s combined weight, which amounts to only about 6 lbs of wild land mammal per person,” says Milo. “In other words, our research shows, in quantifiable terms, the magnitude of our influence and how our decisions and choices in the coming years will determine what’s left of nature for future generations.”

Other participants in the study include Uri Moran, Dr. Ron Sender, Dr. Yuval Rosenberg, Dr. Yinon M. Bar-On, Tomer Antman and Dr. Elad Noor of Weizmann’s Plant and Environmental Sciences Department; Prof. Shai Meiri of Tel Aviv University; and Dr. Uri Roll of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Mammal Numbers:

- The combined weight (biomass) of humans is 390 million tonnes.

- The livestock biomass is 630 million tonnes, dominated by cattle, at 420 million tonnes.

- The biomass of wild land mammals is 20 million tonnes.

- Ten species account for about 40 percent of the biomass of all wild land mammals.

- White-tailed deer, known to many from the animated Disney movie Bambi, have the largest biomass of all wild land mammals, followed by wild boar and African elephants.

- The biomass of pigs alone is nearly double that of all wild land mammals.

- Domestic dogs’ biomass equals that of all wild land mammals combined.

- The biomass of marine mammals is 40 million tonnes.

- Fin whales have the largest biomass of all marine mammals. Sperm whales and humpbacks hold the second and third slots, respectively.

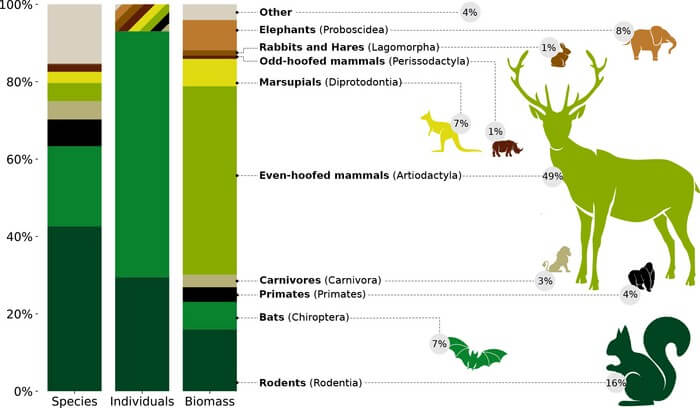

- Biomass studies offer a different perspective on the animal world compared to other metrics. For instance, the 1,200 species of bats account for a fifth of all land mammal species and two-thirds of all wild mammals by head count (total number of individuals). However, they make up only 10 percent of the biomass of wild land mammals.

Prof. Ron Milo is head of the Mary and Tom Beck Canadian Center for Alternative Energy Research; his research is supported by the Schwartz Reisman Collaborative Science Program; the Ullmann Family Foundation and the Yotam Project. Prof. Milo is the incumbent of the Charles and Louise Gartner Professorial Chair.