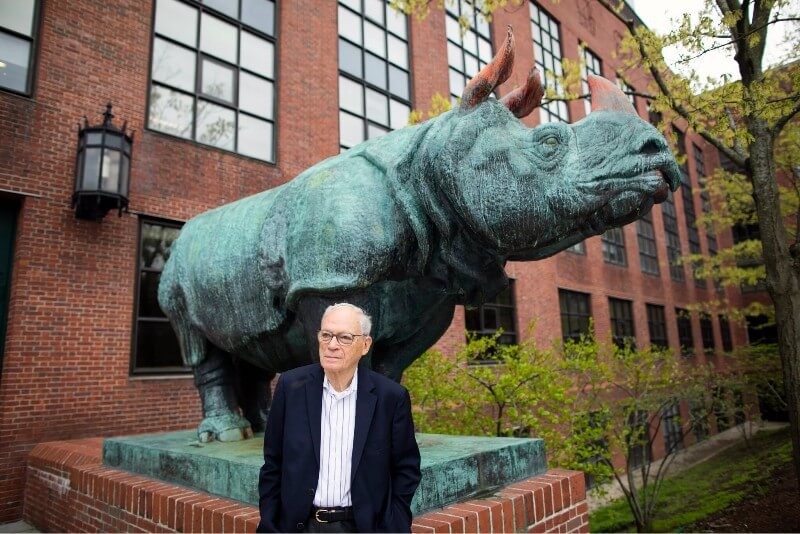

Harvard microbiologist Richard Losick is still teaching at age 80 and did so Saturday, telling an audience of well over 100 at Harvard’s Northwest Building the story of DNA’s discovery — the real story — one of insights ahead of their time, of recognition denied and buried by incorrect dogma, and of credit eventually going to another.

The tale was compelling enough itself, bearing lessons not just about the science of life that Losick has loved and passed on to others for decades, but also about the unpredictability of science — like any enterprise — once humans get involved in it.

The bonus for the crowd, though, was the revered scientist telling it. The Maria Moors Cabot Professor of Biology has been at Harvard for 55 years, arriving as a junior fellow in 1968. On Saturday the microbial community came together for the Harvard Microbial Sciences Initiative’s 20th annual Microbial Sciences Symposium, a daylong affair that was capped by the presentation to Losick of the first MSI Distinguished Achievement Award.

Using the bacterium Bacillus subtilis as a model, Losick has investigated some of life’s most basic processes, from DNA expression to how cells communicate, from protein activity to bacterial colonies and biofilms. In addition to his scientific work, Losick is known for his dedication to undergraduate teaching. As a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Professor, Losick is actively engaged in reforming undergraduate science education, making it more interdisciplinary and hands-on.

Niels Bradshaw, assistant professor of biochemistry at Brandeis University, was a postdoc with Losick, and called him “my science hero, my mentor, my friend, and now my collaborator.”

“Rich has been many of those things to many people in this room, some much longer than me,” Bradshaw said. “He’s also had a singularly important impact on life sciences research for longer than I’ve been alive.”

The event itself brought almost 300 students, faculty, and researchers from Harvard and beyond to the Northwest Building for talks about everything from using artificial intelligence to fight pathogens to bacterial metabolism and physiology to host and predator impacts on pathogens to evolutionary and historical insights into microbiology.

The program also included several “Science Art Features” that highlighted the beauty of the microbial world, and a talk and demonstration on chocolate fermentation.

“In terms of audience, my work is aimed at everyone,” said artist Rogan Brown via video, referring to his elaborate paper sculptures of microbial colonies. “People can respond to it on a purely aesthetic level, or they can delve deeper into the ideas behind the sculpture. Also, it is my goal to show that beauty can be found in the most unlikely places, and it is both art and science that shine a light into those places.”

Peter Girguis, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and one of the event’s organizers, said part of its aim was to communicate science in as many ways as possible, whether through the feast for the eyes presented by visual artists, for the mind through scientific talks, or directly to the stomach with a dose of chocolate.

In his award address, Losick told the story of a team, led by Oswald Avery, that in 1943 purified what they believed was the “transforming principle” that carried the information that allowed cells of one type to change into another.

He outlined Avery’s work, carried out at the Rockefeller Institute in New York City, which involved two different strains of the bacteria that causes pneumonia. One was virulent and formed smooth-looking colonies on plates of nutrient agar. The second, nonvirulent, formed rough-looking colonies.

By purifying molecules that they believed to be the “transforming principle,” they were able to change batches of nonvirulent into virulent strains. They determined that the “transforming principle” was DNA, a molecule that was already known to science, but whose foundational role in carrying genetic information was not.

Instead of gaining praise for the work, Avery came under fire. The prevailing hypothesis about how genetic information was carried in the cell was that it was done by proteins, which are more complex molecules than DNA.

One who held that theory was Alfred Mirsky, also at the Rockefeller Institute. Mirsky insisted that Avery’s samples were contaminated with traces of protein that explained their functionality. Despite efforts by Avery’s team, which included Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty, to produce ever-purer DNA samples, Mirsky kept up the drumbeat for years. Avery, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize several times, wound up seeing the prize go to Alfred Hershey, Max Delbruck, and Salvador Luria for experiments conducted years later that confirmed DNA as the body’s genetic material.

In explaining how Avery wound up being ignored, Losick attributed part of it to the strength of the prevailing dogma that genetic material had to be a protein, in part because DNA, with just four repeating bases, was thought not to be complex enough.

He also pointed to Mirsky’s efforts to discredit Avery, aided by Avery’s low-key personality. In addition, he said, the Nobel winners were part of a well-known group of biologists who explored bacterial genetics, called the “Phage Group,” because of their use of bacteriophages, a type of virus that infects bacteria.

“To me, the Phage Group and nucleic acid biochemists lived in different intellectual worlds. And the discovery of Avery was simply ahead of its time and largely went unappreciated. Nevertheless and looking back, we can say it represents one of the greatest of all discoveries in the biological sciences in the last century,” Losick said. “Today we celebrate the 20th anniversary of Microbial Sciences Initiative. … Let’s also celebrate the 80th anniversary of Oswald Avery’s transformative discovery in 1943 and — if you’ll permit me — of vastly less significance, yours truly is celebrating my 80th year on this planet. I was born the same year as the Avery, McCarty, MacLeod experiment, but to be honest was too young to appreciate it.”