Key Points

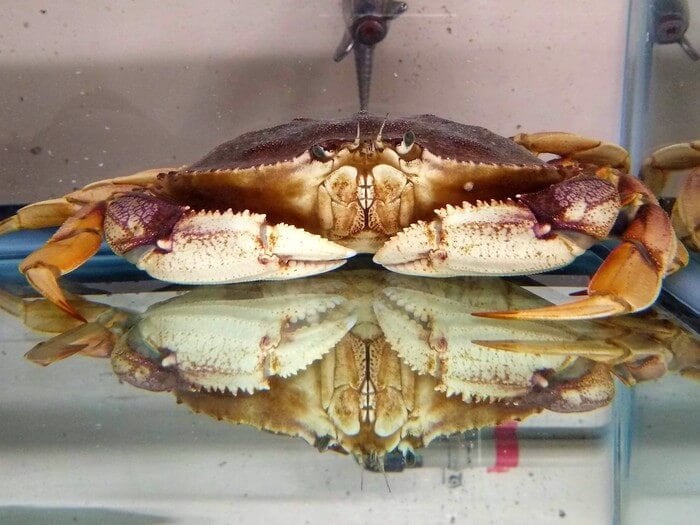

- Ocean acidification, which is the result of the Earth’s oceans becoming more acidic due to absorbing more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, is causing a decline in the populations of Dungeness crabs, an economically important species found along the Pacific coast.

- The sense of smell is essential for crabs to find food, mates, and suitable habitats, and ocean acidification is reducing their ability to do so.

- This reduction could impact other important species such as Alaskan king and snow crabs.

A study by the University of Toronto Scarborough shows that climate change is leading to the loss of the sense of smell in commercially important marine crabs.

The research, which focused on Dungeness crabs, found ocean acidification caused them to sniff less and impacted their ability to detect food odours, resulting in a thinning of their populations. The study also found that ocean acidification led to a decrease in the activity of sensory nerves responsible for smell.

The study reveals that the loss of sense of smell in marine crabs is climate-related and partially explains the decline in their numbers.

According to the study’s co-author, Cosima Porteus, crabs sniff through a process called flicking, where they flick their small antenna through the water to detect odours. “Crabs increase their flicking rate when they detect an odour they are interested in, but in crabs that were exposed to ocean acidification, the odour had to be 10 times more concentrated before we saw an increase in flicking,” says Porteus.

Tiny neurons responsible for smell are located inside these antennae, which send electrical signals to the brain. However, when crabs were exposed to ocean acidification, they sniffed less and required odours to be 10 times stronger before they started to sniff more. “These are active cells and if they aren’t detecting odours as much, they might be shrinking to conserve energy. It’s like a muscle that will shrink if you don’t use it,” she says.

Porteus says that the reduced food detection could impact other economically important species like Alaskan king and snow crabs because their sense of smell functions the same way.

The study was published in the journal Global Change Biology and was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.