If you search for “electronic implants” in an image search, you’ll find a variety of devices like pacemakers, cochlear implants, and even futuristic brain and retinal microchips. These implants usually have electrodes, which are small conductive elements that stimulate muscles and nerves by attaching to target tissues.

However, the problem with current implantable electrodes is that they are made of rigid metals that can cause tissue aggravation and inflammation over time, leading to scarring and a decline in the implant’s performance.

Now, engineers at MIT have created a metal-free material that has a consistency similar to Jell-O but can conduct electricity like conventional metals. This material can be turned into a printable ink and used to make flexible and rubbery electrodes. It’s a type of high-performance conducting polymer hydrogel that could potentially replace metal electrodes in the future, offering a more natural and biocompatible option.

According to Hyunwoo Yuk, co-founder of SanaHeal, a medical device startup, “This material operates like metal electrodes but is made from gels that are similar to our bodies, and with similar water content. It’s like an artificial tissue or nerve.”

Xuanhe Zhao, a professor of mechanical engineering and civil and environmental engineering at MIT, believes that they have created a tough and robust electrode that resembles Jell-O and can potentially replace metal in stimulating nerves and interfacing with organs like the heart and brain.

The researchers used a special method to mix conductive polymers with hydrogels to enhance the electrical and mechanical properties of both materials. By slightly separating the ingredients, they were able to create a gel with continuous strands of conductive polymers for electricity transmission and hydrogel for mechanical strength and flexibility.

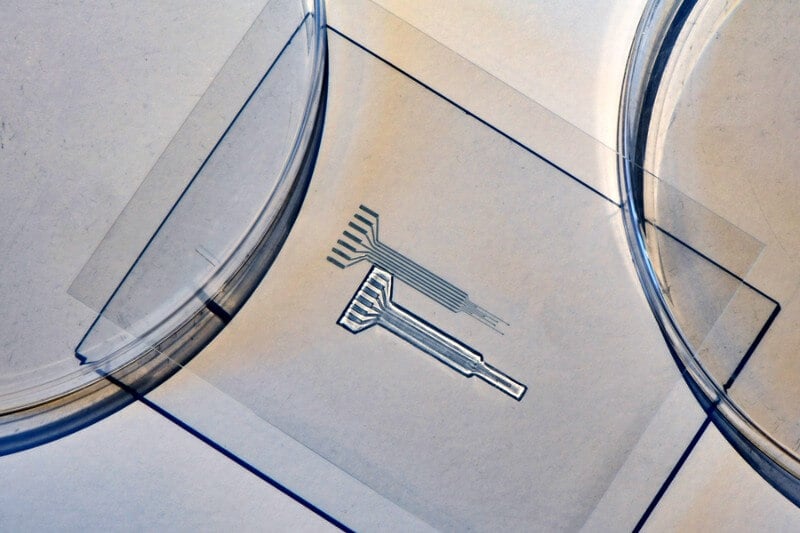

The gel was then turned into an ink and 3D printed onto pure hydrogel films, forming patterns similar to traditional metal electrodes. The printed electrodes were implanted in rats’ hearts, sciatic nerves, and spinal cords and tested for up to two months. The devices remained stable, caused little inflammation or scarring, and effectively transmitted electrical pulses and stimulated motor activity.

The researchers see potential applications for this new material in people recovering from heart surgery, where the gel could replace metal electrodes and minimize complications and side effects. They are also working on improving the material’s lifetime and performance to be used in long-term implants such as pacemakers and deep-brain stimulators.

Ultimately, the goal of the MIT team is to replace materials like glass, ceramic, and metal inside the body with a more benign and long-lasting alternative like Jell-O.

Funding for this research is partially provided by the National Institutes of Health.