The origin of bees is tens of millions of years older than most previous estimates, a new study shows.

A team led by Washington State University researchers traced the bee genealogy back more than 120 million years to an ancient supercontinent, Gondwana, which included today’s continents of Africa and South America.

In a study that proposes a new evolutionary history of bees, the researchers found evidence that bees originated earlier, diversified faster and spread wider than many scientists previously suspected. They published their findings in the journal Current Biology.

“There’s been a longstanding puzzle about the spatial origin of bees,” said Silas Bossert, assistant professor with WSU’s Department of Entomology, who co-led the project with Eduardo Almeida, associate professor at the University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Working with collaborators on every continent who assisted with sampling and computational analysis, Bossert and Almeida’s team sequenced and compared genes from more than 200 bee species. They compared them with traits from 185 different bee fossils, as well as extinct species, developing an evolutionary history and genealogical models for historical bee distribution. In what may be the broadest genomic study of bees to date, they analyzed hundreds to thousands of genes at a time to make sure that the relationships they inferred were correct.

“This is the first time we have broad genome-scale data for all seven bee families,” said co-author Elizabeth Murray, a WSU assistant professor of entomology.

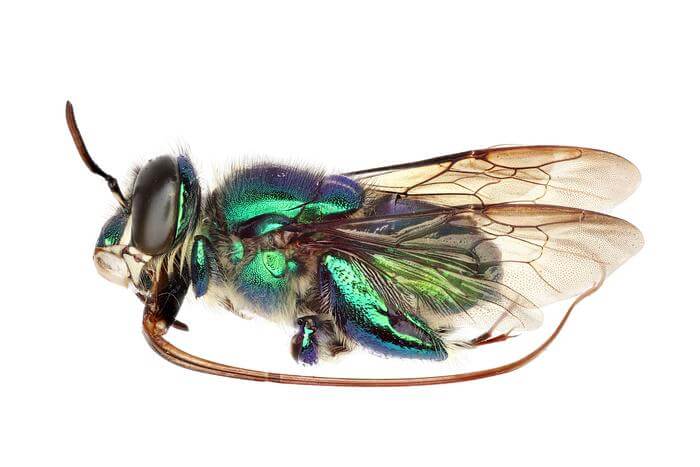

Previous research established that the first bees likely evolved from wasps, transitioning from predators to collectors of nectar and pollen. This study shows they arose in arid regions of western Gondwana during the early Cretaceous period.

“For the first time, we have statistical evidence that bees originated on Gondwana,” Bossert said. “We now know that bees are originally southern hemisphere insects.”

The researchers found evidence that as the new continents formed, bees moved north, diversifying and spreading in a parallel partnership with angiosperms, the flowering plants. Later, they colonized India and Australia. All major families of bees appeared to split off prior to the dawn of the Tertiary period, 65 million years ago—the era when dinosaurs became extinct.

The tropical regions of the western hemisphere have an exceptionally rich flora, and that diversity may be due to their longtime association with bees, authors noted. One quarter of all flowering plants belong to the large and diverse rose family, which make up a significant share of the tropical and temperate host plants for bees.

Bossert’s team plans to continue their efforts, sequencing and studying the genetics and history of more species of bees. Their findings are a useful first step in revealing how bees and flowering plants evolved together. Understanding how bees spread and filled their modern ecological niches could also help keep pollinator populations healthy.

“People are paying more attention to the conservation of bees and are trying to keep these species alive where they are,” Murray said. “This work opens the way for more studies on the historical and ecological stage.”

Additional contributors included Felipe Freitas, Washington State University; Bryan Danforth, Cornell University; Charles Davis, Harvard University; Bonnie Blaimer, Tamara Spasojevic, and Seán Brady, Smithsonian Institution; Patrícia Ströher and Marcio Pie, Federal University of Paraná, Brazil; Michael Orr, State Museum of Natural History, Stuttgart; Laurence Packer, York University; Michael Kuhlmann, University of Kiel; and Michael G. Branstetter, U.S. Department of Agriculture.