Gray whales that spend their summers feeding in the shallow waters off the Pacific Northwest coast have undergone a significant decline in body length since around the year 2000, according to a new Oregon State University study. This alarming trend could have serious implications for the health and reproductive success of the affected whales, and raises concerns about the state of the food web in which they coexist.

“This could be an early warning sign that the abundance of this population is starting to decline, or is not healthy,” said K.C. Bierlich, co-author on the study and an assistant professor at OSU’s Marine Mammal Institute in Newport. “And whales are considered ecosystem sentinels, so if the whale population isn’t doing well, that might say a lot about the environment itself.”

Pacific Coast Feeding Group Whales Shrinking at an Alarming Rate

The study, published in Global Change Biology, focused on the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG), a small subset of about 200 gray whales within the larger Eastern North Pacific (ENP) population of around 14,500. This subgroup remains closer to shore along the Oregon coast, feeding in shallower, warmer waters than the Arctic seas where the majority of the gray whale population spends most of the year.

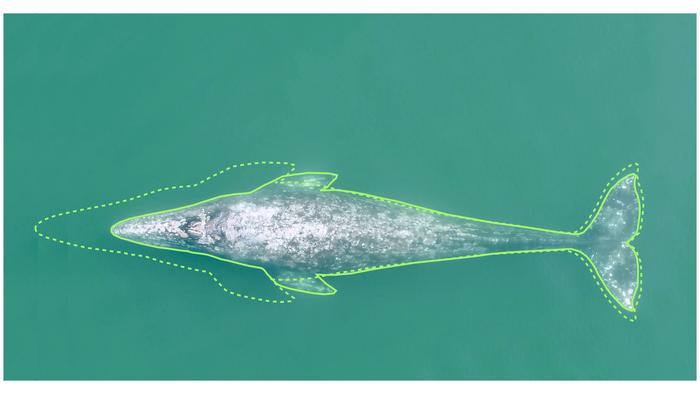

Using images from 2016-2022 of 130 individual whales with known or estimated age, researchers determined that a full-grown gray whale born in 2020 is expected to reach an adult body length that is 1.65 meters (about 5 feet, 5 inches) shorter than a gray whale born prior to 2000. For PCFG gray whales that grow to be 38-41 feet long at full maturity, this accounts for a loss of more than 13% of their total length.

“In general, size is critical for animals,” said Enrico Pirotta, lead author on the study and a researcher at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. “It affects their behavior, their physiology, their life history, and it has cascading effects for the animals and for the community they’re a part of.”

Consequences of Smaller Body Size and Potential Causes

Smaller body size can have significant consequences for gray whales, including reduced survival rates for calves and lower reproductive success for adults. Researchers are also concerned that smaller body size and lower energy reserves may make the whales less resilient to injuries from boat strikes and fishing gear entanglement.

The study also examined the patterns of the ocean environment that likely regulate food availability for these gray whales off the Pacific coast by tracking cycles of “upwelling” and “relaxation” in the ocean. The data show that whale size declined concurrently with changes in the balance between upwelling and relaxation.

“We haven’t looked specifically at how climate change is affecting these patterns, but in general we know that climate change is affecting the oceanography of the Northeast Pacific through changes in wind patterns and water temperature,” Pirotta said. “And these factors and others affect the dynamics of upwelling and relaxation in the area.”

Researchers now have new questions about the downstream consequences of the decline in body size and the factors that could be contributing to it. “We’re heading into our ninth field season studying this PCFG subgroup,” Bierlich said. “This is a powerful dataset that allows us to detect changes in body condition each year, so now we’re examining the environmental drivers of those changes.”