Gravitational wave detectors, LIGO and Virgo, have detected a population of massive black holes whose origin is one of the biggest mysteries in modern astronomy.

According to one hypothesis, these objects may have formed in the very early Universe and may compose dark matter, a mysterious substance filling the Universe. A team of scientists from the OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) survey from the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw have announced the results of nearly 20-year-long observations indicating that such massive black holes may comprise at most a few percent of dark matter. Another explanation, therefore, is needed for gravitational wave sources. The results of the study were published in two articles, in Nature and the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

Various astronomical observations indicate that ordinary matter, which we can see or touch, comprises only 5% of the total mass and energy budget of the Universe. In the Milky Way, for every 1 kg of ordinary matter in stars, there is 15 kg of “dark matter,” which does not emit any light and interacts only by means of its gravitational pull.

“The nature of dark matter remains a mystery. Most scientists think it is composed of unknown elementary particles,” says Dr Przemek Mróz from the Astronomical Observatory, University of Warsaw, the lead author of both articles. “Unfortunately, despite decades of efforts, no experiment (including experiments carried out with the Large Hadron Collider) has found new particles that could be responsible for dark matter.”

Since the first detection of gravitational waves from a merging pair of black holes in 2015, the LIGO and Virgo experiments have detected more than 90 such events. Astronomers noticed that black holes detected by LIGO and Virgo are typically significantly more massive (20–100 solar masses) than those known previously in the Milky Way (5–20 solar masses).

“Explaining why these two populations of black holes are so different is one of the biggest mysteries of modern astronomy,” says Dr Mróz.

One possible explanation postulates that LIGO and Virgo detectors have uncovered a population of primordial black holes that may have formed in the very early Universe. Their existence was first proposed over 50 years ago by the famous British theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and, independently, by the Soviet physicist Yakov Zeldovich.

“We know that the early Universe was not ideally homogeneous – small density fluctuations gave rise to current galaxies and galaxy clusters,” says Dr Mróz. “Similar density fluctuations, if they exceed a critical density contrast, may collapse and form black holes.”

Since the first detection of gravitational waves, more and more scientists have been speculating that such primordial black holes may comprise a significant fraction, if not all, of dark matter.

Fortunately, this hypothesis can be verified with astronomical observations. We observe that copious amounts of dark matter exist in the Milky Way. If it were composed of black holes, we should be able to detect them in our cosmic neighborhood. Is this possible, given that black holes do not emit any detectable light?

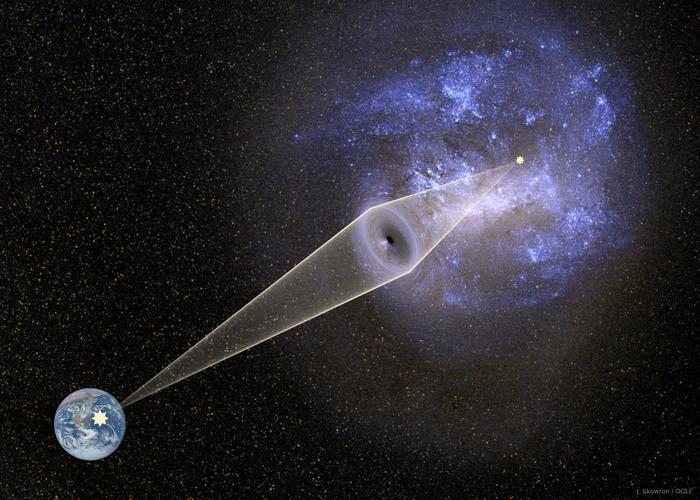

According to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, light may be bent and deflected in the gravitational field of massive objects, a phenomenon called gravitational microlensing.

“Microlensing occurs when three objects – an observer on Earth, a source of light, and a lens – virtually ideally align in space,” says Prof. Andrzej Udalski, the principal investigator of the OGLE survey. “During a microlensing event, the source’s light may be deflected and magnified, and we observe a temporary brightening of the source’s light.”

The duration of the brightening depends on the mass of the lensing object: the higher the mass, the longer the event. Microlensing events by solar mass objects typically last several weeks, whereas those by black holes that are 100 more massive than the Sun would last a few years.

The idea of using gravitational microlensing to study dark matter is not new. It was first proposed in the 1980s by the famous Polish astrophysicist Bohdan Paczyński. His idea inspired the start of three major experiments: Polish OGLE, American MACHO, and French EROS. The first results from these experiments demonstrated that black holes less massive than one solar mass may comprise less than 10 percent of dark matter. These observations were not, however, sensitive to extremely long-timescale microlensing events and, therefore, not sensitive to massive black holes, similar to those recently detected with gravitational-wave detectors.

In the new article in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, OGLE astronomers present the results of nearly 20-year-long photometric monitoring of almost 80 million stars located in a nearby galaxy, called the Large Magellanic Cloud, and the searches for gravitational microlensing events. The analyzed data were collected during the third and fourth phases of the OGLE project from 2001 to 2020.

“This data set provides the longest, largest, and most accurate photometric observations of stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud in the history of modern astronomy,” says Prof. Udalski.

The second article, published in Nature, discusses the astrophysical consequences of the findings.

“If the entire dark matter in the Milky Way was composed of black holes of 10 solar masses, we should have detected 258 microlensing events,” says Dr Mróz. “For 100 solar mass black holes, we expected 99 microlensing events. For 1000 solar mass black holes – 27 microlensing events.”

In contrast, the OGLE astronomers have found only 13 microlensing events. Their detailed analysis demonstrates that all of them can be explained by the known stellar populations in the Milky Way or the Large Magellanic Cloud itself, not by black holes.

“That indicates that massive black holes can compose at most a few percent of dark matter,” says Dr Mróz.

The detailed calculations demonstrate that black holes of 10 solar masses may comprise at most 1.2% of dark matter, 100 solar mass black holes – 3.0% of dark matter, and 1000 solar mass black holes – 11% of dark matter.

“Our observations indicate that primordial black holes cannot comprise a significant fraction of the dark matter and, simultaneously, explain the observed black hole merger rates measured by LIGO and Virgo,” says Prof. Udalski.

Therefore, other explanations are needed for massive black holes detected by LIGO and Virgo. According to one hypothesis, they formed as a product of the evolution of massive, low-metallicity stars. Another possibility involves mergers of less massive objects in dense stellar environments, such as globular clusters.

“Our results will remain in astronomy textbooks for decades to come,” adds Prof. Udalski.