A groundbreaking study has uncovered the first documented case of Down syndrome in Neandertals, shedding new light on the social behavior of our ancient relatives. The discovery, made by an international team of researchers including faculty from Binghamton University, provides compelling evidence of altruistic care in Neandertal communities.

Unearthing “Tina”: A Prehistoric Medical Mystery

The skeletal remains of a Neandertal child, affectionately named “Tina,” were found in Cova Negra, a cave in Valencia, Spain. This site has long been a treasure trove of Neandertal discoveries. Professor Valentín Villaverde from the University of Valencia explained, “The excavations at Cova Negra have been key to understanding the way of life of the Neandertals along the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula and have allowed us to define the occupations of the settlement: of short temporal duration and with a small number of individuals, alternating with the presence of carnivores.”

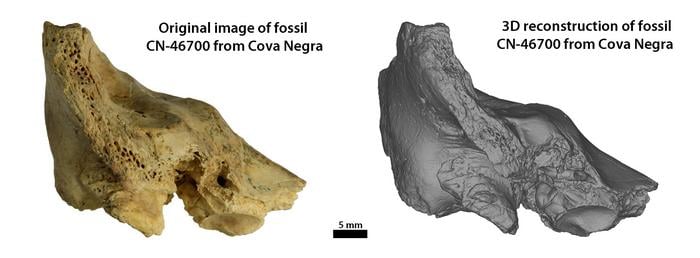

Using advanced micro-computed tomography scans, researchers analyzed a small cranial fragment of Tina’s right temporal bone. They discovered that the child suffered from a congenital inner ear pathology associated with Down syndrome, resulting in severe hearing loss and disabling vertigo. Despite these challenges, Tina survived to at least 6 years of age, suggesting extensive care from her social group.

Rewriting Neandertal Social Behavior

While previous evidence has shown that Neandertals cared for disabled adults, Tina’s case is unique. It represents the first instance of care for a child who could not reciprocate, indicating true altruism in Neandertal society.

Mercedes Conde, lead author of the study from the University of Alcalá, emphasized the significance of this finding: “What was not known until now was any case of an individual who had received help, even if they could not return the favor, which would prove the existence of true altruism among Neandertals. That is precisely what the discovery of ‘Tina’ means.”

Binghamton University Professor Rolf Quam praised the research, stating, “This is a fantastic study, combining rigorous archaeological excavations, modern medical imaging techniques and diagnostic criteria to document Down syndrome in a Neandertal individual for the first time. The results have significant implications for our understanding of Neandertal behavior.”

This discovery challenges previous notions about Neandertal social structures and behaviors. It suggests a level of compassion and community support previously unrecognized in our ancient relatives, painting a more complex picture of Neandertal society.

The study, titled “The child who lived: Down syndrome among Neandertals?” was published in Science Advances, marking a significant milestone in our understanding of prehistoric human behavior and social structures.