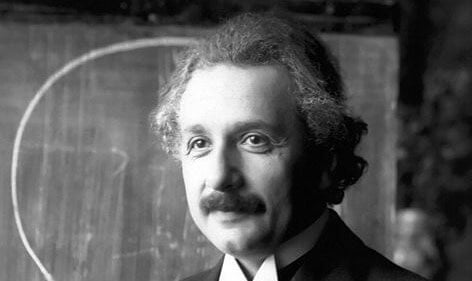

The left and right hemispheres of Albert Einstein’s brain were unusually well connected to each other and may have contributed to his brilliance, according to a new study conducted in part by Florida State University evolutionary anthropologist Dean Falk.

“This study, more than any other to date, really gets at the ‘inside’ of Einstein’s brain,” Falk said. “It provides new information that helps make sense of what is known about the surface of Einstein’s brain.”

The study, “The Corpus Callosum of Albert Einstein’s Brain: Another Clue to His High Intelligence,” was published in the journal Brain. Lead author Weiwei Men of East China Normal University’s Department of Physics developed a new technique to conduct the study, which is the first to detail Einstein’s corpus callosum, the brain’s largest bundle of fibers that connects the two cerebral hemispheres and facilitates interhemispheric communication.

“This technique should be of interest to other researchers who study the brain’s all-important internal connectivity,” Falk said.

Men’s technique measures and color-codes the varying thicknesses of subdivisions of the corpus callosum along its length, where nerves cross from one side of the brain to the other. These thicknesses indicate the number of nerves that cross and therefore how “connected” the two sides of the brain are in particular regions, which facilitate different functions depending on where the fibers cross along the length. For example, movement of the hands is represented toward the front and mental arithmetic along the back.

In particular, this new technique permitted registration and comparison of Einstein’s measurements with those of two samples — one of 15 elderly men and one of 52 men Einstein’s age in 1905. During his so-called “miracle year” at 26 years old, Einstein published four articles that contributed substantially to the foundation of modern physics and changed the world’s views about space, time, mass and energy.

The research team’s findings show that Einstein had more extensive connections between certain parts of his cerebral hemispheres compared to both younger and older control groups.

The research of Einstein’s corpus callosum was initiated by Men, who requested the high-resolution photographs that Falk and other researchers published in 2012 of the inside surfaces of the two halves of Einstein’s brain. In addition to Men, the current research team included Falk, who served as second author; Tao Sun of the Washington University School of Medicine; and, from East China Normal University’s Department of Physics, Weibo Chen, Jianqi Li, Dazhi Yin, Lili Zang and Mingxia Fan.