The same tiny cellulose crystals that give trees and plants their high strength, light weight and resilience, have now been shown to have the stiffness of steel.

The nanocrystals might be used to create a new class of biomaterials with wide-ranging applications, such as strengthening construction materials and automotive components.

Calculations using precise models based on the atomic structure of cellulose show the crystals have a stiffness of 206 gigapascals, which is comparable to steel, said Pablo D. Zavattieri, a Purdue University assistant professor of civil engineering.

“This is a material that is showing really amazing properties,” he said. “It is abundant, renewable and produced as waste in the paper industry.”

Findings are detailed in a research paper featured on the cover of the December issue of the journal Cellulose.

“It is very difficult to measure the properties of these crystals experimentally because they are really tiny,” Zavattieri said. “For the first time, we predicted their properties using quantum mechanics.”

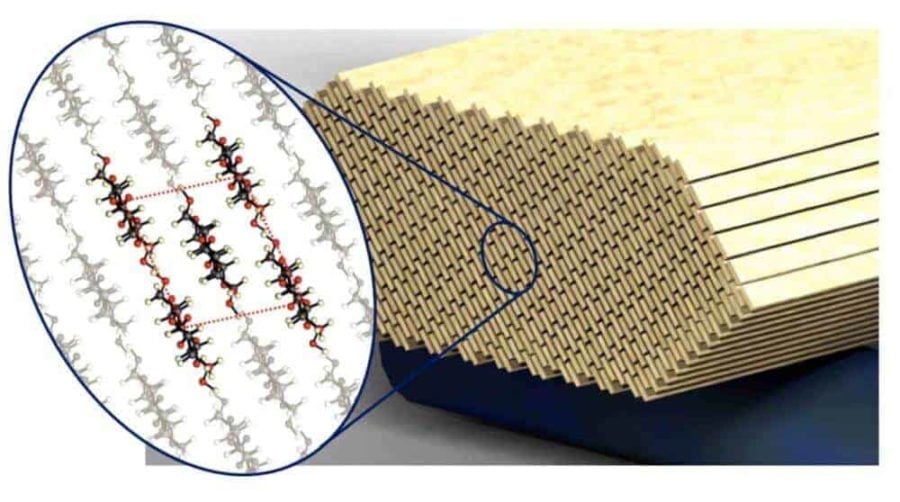

The nanocrystals are about 3 nanometers wide by 500 nanometers long – or about 1/1,000th the width of a grain of sand – making them too small to study with light microscopes and difficult to measure with laboratory instruments.

The paper was authored by Purdue doctoral student Fernando L. Dri; Louis G. Hector Jr., a researcher from the Chemical Sciences and Materials Systems Laboratory at General Motors Research and Development Center; Robert J. Moon, a researcher from the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Products Laboratory; and Zavattieri.

The findings represent a milestone in understanding the fundamental mechanical behavior of the cellulose nanocrystals.

“It is also the first step towards a multiscale modeling approach to understand and predict the behavior of individual crystals, the interaction between them, and their interaction with other materials,” Zavattieri said. “This is important for the design of novel cellulose-based materials as other research groups are considering them for a huge variety of applications, ranging from electronics and medical devices to structural components for the automotive, civil and aerospace industries.”

The cellulose nanocrystals represent a potential green alternative to carbon nanotubes for reinforcing materials such as polymers and concrete. Applications for biomaterials made from the cellulose nanocrystals might include biodegradable plastic bags, textiles and wound dressings; flexible batteries made from electrically conductive paper; new drug-delivery technologies; transparent flexible displays for electronic devices; special filters for water purification; new types of sensors; and computer memory.

Cellulose could come from a variety of biological sources including trees, plants, algae, ocean-dwelling organisms called tunicates, and bacteria that create a protective web of cellulose.

“With this in mind, cellulose nanomaterials are inherently renewable, sustainable, biodegradable and carbon-neutral like the sources from which they were extracted,” Moon said. “They have the potential to be processed at industrial-scale quantities and at low cost compared to other materials.”

Biomaterials manufacturing could be a natural extension of the paper and biofuels industries, using technology that is already well-established for cellulose-based materials.

“Some of the byproducts of the paper industry now go to making biofuels, so we could just add another process to use the leftover cellulose to make a composite material,” Moon said. “The cellulose crystals are more difficult to break down into sugars to make liquid fuel. So let’s make a product out of it, building on the existing infrastructure of the pulp and paper industry.”

Their surface can be chemically modified to achieve different surface properties.

Their surface can be chemically modified to achieve different surface properties.

“For example, you might want to modify the surface so that it binds strongly with a reinforcing polymer to make a new type of tough composite material, or you might want to change the chemical characteristics so that it behaves differently with its environment,” Moon said.

Zavattieri plans to extend his research to study the properties of alpha-chitin, a material from the shells of organisms including lobsters, crabs, mollusks and insects. Alpha-chitin appears to have similar mechanical properties as cellulose.

“This material is also abundant, renewable and waste of the food industry,” he said.