A new study correlating brain activity with how people make decisions suggests that when individuals engage in risky behavior, such as drunk driving or unsafe sex, it’s probably not because their brains’ desire systems are too active, but because their self-control systems are not active enough.

This might have implications for how health experts treat mental illness and addiction or how the legal system assesses a criminal’s likelihood of committing another crime.

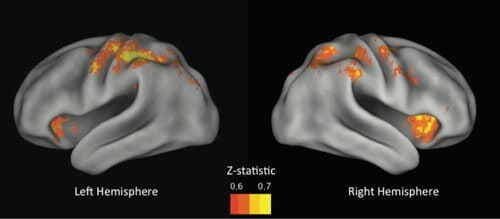

Researchers from The University of Texas at Austin, UCLA and elsewhere analyzed data from 108 subjects who sat in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner — a machine that allows researchers to pinpoint brain activity in vivid, three-dimensional images — while playing a video game that simulates risk-taking.

The researchers used specialized software to look for patterns of activity across the whole brain that preceded a person’s making a risky choice or a safe choice in one set of subjects. Then they asked the software to predict what other subjects would choose during the game based solely on their brain activity. The software accurately predicted people’s choices 71 percent of the time.

“These patterns are reliable enough that not only can we predict what will happen in an additional test on the same person, but on people we haven’t seen before,” said Russell Poldrack, director of UT Austin’s Imaging Research Center and professor of psychology and neuroscience.

When the researchers trained their software on much smaller regions of the brain, they found that just analyzing the regions typically involved in executive functions such as control, working memory and attention was enough to predict a person’s future choices. Therefore, the researchers concluded, when we make risky choices, it is primarily because of the failure of our control systems to stop us.

“We all have these desires, but whether we act on them is a function of control,” said Sarah Helfinstein, a postdoctoral researcher at UT Austin and lead author of the study that appears online this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Helfinstein said that additional research could focus on how external factors, such as peer pressure, lack of sleep or hunger, weaken the activity of our brains’ control systems when we contemplate risky decisions.

“If we can figure out the factors in the world that influence the brain, we can draw conclusions about what actions are best at helping people resist risks,” said Helfinstein.

To simulate features of real-world risk-taking, the researchers used a video game called the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) that past research has shown correlates well with self-reported risk-taking such as drug and alcohol use, smoking, gambling, driving without a seatbelt, stealing and engaging in unprotected sex.

While playing the BART, the subject sees a balloon on the screen and is asked to make either a risky choice (inflate the balloon a little and earn a few cents) or a safe choice (stop the round and “cash out,” keeping whatever money was earned up to that point). Sometimes inflating the balloon causes it to burst and the player loses all the cash earned from that round. After each successful balloon inflation, the game continues with the chance of earning another standard-sized reward or losing an increasingly large amount. Many health-relevant risky decisions share this same structure, such as when deciding how many alcoholic beverages to drink before driving home or how much one can experiment with drugs or cigarettes before developing an addiction.

The data for this study came from the Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics at UCLA, which recruited adults from the Los Angeles area for researchers to examine differences in response inhibition and working memory between healthy adults and patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Only data collected from healthy participants were included in the present analyses.

Other researchers on the study include: Tom Schonberg and Jeanette A. Mumford at The University of Texas at Austin; Katherine H. Karlsgodt at Zucker Hillside Hospital and the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research; Eliza Congdon, Fred W. Sabb, Edythe D. London and Robert M. Bilder at UCLA; and Tyrone D. Cannon at Yale University.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics and the Tennenbaum Center for the Biology of Creativity.

Link to the paper “Predicting risky choices from brain activity patterns”: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2014/01/29/1321728111.full.pdf+html

Do you take a risk, as this University of Texas/Yale study concludes, because you don’t foresee how you can avoid the risk?

By making this finding, the study essentially assigns the bases of a person’s risky decisions to their thinking brain.

I’m not persuaded. In my view, the conclusion was reached because the study’s design only engaged the thinking part of the subjects’ brains with a video game task involving popping balloons. Other studies find that task performance and beliefs about task responses are solely thinking brain exercises.

If the researchers had, instead, designed a study that also engaged the subjects’ feeling and lower brains, the findings may have been different.

Only one of the news articles covered this story with some accuracy, in my opinion, io9.com: “Helfinstein (the lead researcher) doesn’t see any direct, practical applications of the research. After all, people don’t spend their lives in fMRI scanners, so it’s not as if we can tell when people are going to make a risky decision in their day-to-day activities.”

Compare that with the majority of the news coverage, which hijacks the study to try to develop a politically correct meme: “Many health-relevant risky decisions share this same structure, such as when deciding how many alcoholic beverages to drink before driving home or how much one can experiment with drugs or cigarettes before developing an addiction.”

The study found that “..risk taking may be due, in part, to a failure of the control systems necessary to initiate a safe choice.” The brain areas were “primarily located in regions more active when preparing to avoid a risk than when preparing to engage in one..” These areas include the “..bilateral parietal and motor regions, anterior cingulate cortex, bilateral insula, and bilateral lateral orbitofrontal cortex..”

Notice that none of the studied brain areas are part of the feeling or lower brains, although the ventral part of the anterior cingulate cortex and the bilateral insula connect to the feeling brain. Yet the feeling or lower parts of the brain are most often the brain areas that drive real-world risky behaviors such as smoking, drug use, sexual risk taking, and unsafe driving.

So this study was jumped on to develop a meme. But a video game task of popping balloons that engages the thinking brain is NOT informative to the cause-and-effect of the emotions and instincts and impulses from human feeling and lower brains that predominantly drive risky behavior.

At the end of the day, who benefits from the study’s misdirection?

http://surfaceyourrealself.com/2015/02/19/who-benefits-when-research-with-no-practical-application-becomes-a-politically-correct-meme-surfaceyourrealself/