For the past eight years, scientists have been working to make sense of why some satellite data seemed to show the Amazon rain forest “greening-up” during the region’s dry season each year from June to October. The green-up indicated productive, thriving vegetation in spite of limited rainfall.

Now, a new NASA study published today in the journal Nature shows that the appearance of canopy greening is not caused by a biophysical change in Amazon forests, but instead by a combination of shadowing within the canopy and the way that satellite sensors observe the Amazon during the dry season.

Correcting for this artifact in the data, Doug Morton, of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and colleagues show that Amazon forests, at least on the large scale, maintain a fairly constant greenness and canopy structure throughout the dry season. The findings have implications for how scientists seek to understand seasonal and interannual changes in Amazon forests and other ecosystems.

“Scientists who use satellite observations to study changes in Earth’s vegetation need to account for seasonal differences in the angles of solar illumination and satellite observation,” Morton said.

Isolating the apparent green-up mechanism

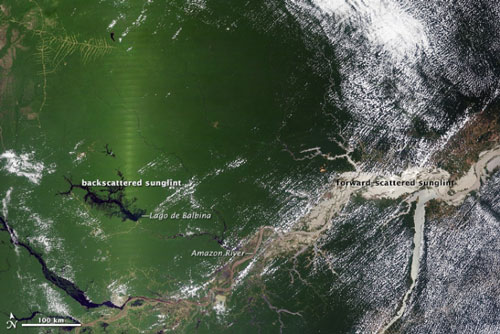

The MODIS, or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, sensors that fly aboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites make daily observations over the huge expanse of Amazon forests. An area is likely covered in green vegetation if sensors detect a relatively small amount of red light – absorbed in abundance by plants for photosynthesis – but see a large amount of near-infrared light, which plants primarily reflect. Scientists use the ratio of red and near-infrared light as a measure of vegetation “greenness.”

Numerous hypotheses have been put forward to explain why Amazon forests appear greener in MODIS data as the dry season progresses. Perhaps young leaves, known to reflect more near-infrared light, replace old leaves? Or, possibly trees add more leaves to capture sunlight in the dry season when the skies are less cloudy.

Unsettled by the lack of definitive evidence explaining the magnitude of the green-up, Morton and colleagues set out to better characterize the phenomenon. They culled satellite observations from MODIS and NASA’s Ice Cloud and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) Geosciences Laser Altimeter System (GLAS), which can provide an independent check on the seasonal differences in Amazon forest structure.

The team next used a theoretical model to demonstrate how changes in forest structure or reflectance properties have distinct fingerprints in MODIS and GLAS data. Only one of the hypothesized mechanisms for the green-up, changes in sun-sensor geometry, was consistent with the satellite observations.

“We think we have uncovered the mechanism for the appearance of seasonal greening of Amazon forests – shadowing within the canopy that changes the amount of near-infrared light observed by MODIS,” Morton said.

Seeing the Amazon in a new light

In June, when the sun is as low and far north as it will get, shadows are abundant. By September, around the time of the equinox, Amazon forests at the equator are illuminated from directly overhead. At this point the forest canopy is shadow-free, highly reflective in the infrared, and therefore very green according to some satellite vegetation indices.

“Around the equinox, the MODIS sensor takes the ‘perfect picture’ with no shadows,” Morton said. “The change in shadows is amplified in MODIS data because the sun is directly behind the sensor at the equinox. This seasonal change in MODIS greenness has nothing to do with how forests are changing.”

In fact, accounting for the changing geometry between the sun and satellite sensor paints a picture of the Amazon that, as a whole, doesn’t change much through the dry season.

“Additional work is needed to verify these results with field measurements, and to explore the influence of drought on corrected vegetation indices,” said Scott Goetz, an ecologist at Woods Hole Research Center in Woods Hole, Mass., who was not involved with the Nature study. “But past interpretations of productivity changes need to be reconsidered in light of these new results.”

Looking forward, Morton sees the results as a reminder and opportunity for remote sensing scientists to work more closely with ground-based ecosystem scientists.

“Scaling our knowledge of forest canopies from measurements of individual leaves to satellite observations of the entire Amazon basin requires a deep understanding of both forest ecology and remote sensing science,” Morton said. “This interdisciplinary collaboration is critical to improve our understanding of the patterns and processes driving changes in vegetation productivity.”