Forecasts of when a volcano is ready to erupt could be a little closer thanks to work by geologists at the University of California, Davis, and Oregon State University published online Feb. 16 in the journal Nature.

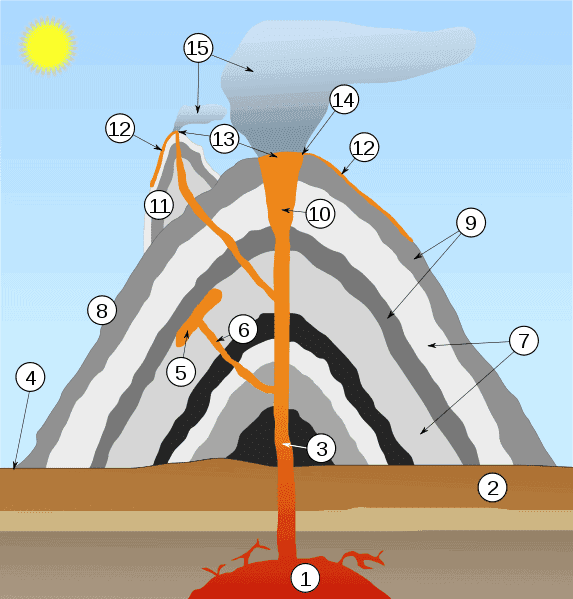

For an eruption to occur, the magma, or molten rock under the volcano must be sufficiently mobile to erupt.

“The question is, what percentage of time is the magma in an eruptible state?” said Kari Cooper, associate professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at UC Davis and lead author on the paper.

“People think about there being this big reservoir of liquid magma under a volcano, but we don’t think it’s in that state all the time,” she said.

The mobility of the magma depends on the amount of crystallization: When it is more than about 50 percent crystalline, it becomes immobile. Crystallization, in turn, depends on the temperature of the rock.

Until now, volcanologists have not known how common it is for magma to be crystalline compared to being mobile and eruptible. The new work shows that at least for Mount Hood, Ore., the magma is mobile less than 10 percent, and perhaps as little as 1 percent of the time.

Cooper and Adam Kent, professor of geology at Oregon State University, studied rocks ejected from previous eruptions at Mount Hood. By analyzing both radioactive isotopes and the distribution of trace elements, they were able to reconstruct the history of the rocks and the conditions to which they had been exposed before they were erupted from the volcano.

The results mean that volcanologists might be able to better assess when a volcano is ready to erupt by using seismic or other remote imaging to look for mostly liquid magma, Cooper said. If eruptible magma is indeed relatively rare, then when it does appear, the risks of an eruption are higher, she said.

Mount Hood is so far the only volcano studied in detail using these techniques. A preliminary survey of data from similar volcanoes around the world shows that they likely follow a similar pattern to Mount Hood, with mobile, “eruptible” magma only being present a small proportion of the time. Cooper and Kent plan further studies to see if these discoveries are widely applicable or unique to Mount Hood.

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation.