Low-income Latino children who experienced one year of Montessori pre-K education at age 4 made dramatic improvements in early achievement and behavior even though they began the year at great risk for school failure, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

In contrast, although low-income black children made gains in school readiness when enrolled in Montessori classrooms as well, they exhibited slightly greater gains when they attended more conventional public school pre-kindergarten programs. The research was published in APA’s Journal of Educational Psychology.

Researcher Arya Ansari, MA, from the University of Texas at Austin, and co-author Adam Winsler, PhD, from George Mason University, looked at data from the Miami School Readiness Project comprising 7,045 Latino and 6,700 black 4-year-olds enrolled in Title I public school pre-K programs in Miami. Title I is the federal law that provides funds to schools where more than 75 percent of the children qualify for a free or reduced-price lunch.

The children’s cognitive, language and fine motor skills were assessed at the beginning and end of the year using a standardized test that looked at their ability to count and match shapes, understand language and write. The test used was available in both Spanish and English. Both parents and teachers reported on the children’s socio-emotional and behavioral problems using another standardized scale, also available in both languages.

“We found that Latino children excelled in Montessori programs across pre-academic and behavioral skills. Latino children began the year at high-risk of school failure and scored well below national averages (25th-35th percentile) on assessments of pre-academic skills (cognitive, language and fine motor skills), but they demonstrated the greatest gains over time,” the researchers wrote. “Conversely, black children exhibited healthy gains in Montessori, but they demonstrated slightly greater gains when attending more conventional pre-K programs.”

For example, black children in Montessori programs ended the year with language skills in the 50th percentile (the national average), but those in conventional pre-K programs ended the year at almost the 60th percentile, according to the study.

The researchers theorized that some of the gains experienced by Latino children might be attributable to the Montessori method’s emphasis on individual instruction and independent learning for Latino children who may still be learning English. Another possible explanation for the large gains by Latino children could be that Montessori curriculum is more phonetic than traditional instruction, stressing sounds and visuals.

“Compared to the English language, Spanish is more consistently phonetic, and there is evidence that at-risk Latino children in elementary school who receive phonetic instruction exhibit positive language and literacy gains,” Ansari said.

Also, the authors noted that the founder of Montessori believed that a child’s culture needs to be incorporated in the school environment in order for that child to thrive academically and socially. “Montessori programs may be better able to integrate Latino children’s socio-cultural backgrounds within the classroom, which, in turn, allows Latino children to transition more smoothly into the educational system,” Ansari said. “This is particularly important for young Latino children who, in the Miami community, often come from culturally and linguistically diverse homes.”

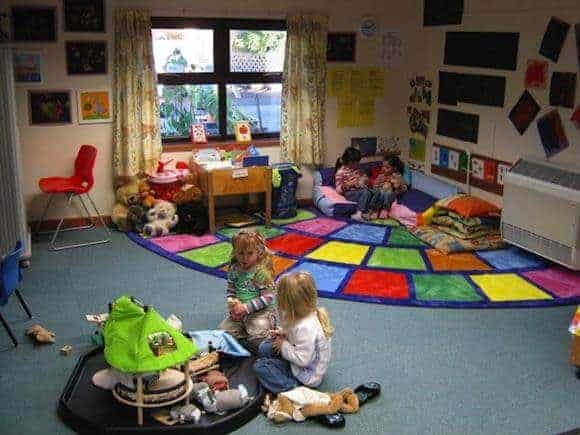

Montessori programs are used in more than 4,000 schools, according to the researchers, and are often characterized by mixed-age classrooms that facilitate individualized learning. Compared to more conventional programs, they contain less teacher-directed structure and more child-directed activities that promote children’s early academic, social and behavioral development.