Law enforcement authorities need to better understand trafficking patterns of cocaine in the United States to address one of the world’s largest illegal drug markets, according to a Michigan State University researcher whose new methodology might help.

Siddharth Chandra, an economist, studied wholesale powdered cocaine prices in 112 cities to identify city-to-city links for the transit of the drug. He used data published by the National Drug Intelligence Center of the U.S. Department of Justice from 2002 to 2011, which field intelligence officers and local, regional and federal law enforcement sources collected through drug arrests and investigations.

“These data enable us to identify suspected links between cities that may have escaped the attention of drug enforcement authorities,” said Chandra, director of MSU’s Asian Studies Center and professor in MSU’s James Madison College. “By identifying patterns and locations, drug policy and enforcement agencies could provide valuable assistance to federal, state and local governments in their decisions on where and how to allocate limited law enforcement resources to mitigate the cocaine problem.”

Chandra analyzed prices for 6,126 pairs of cities for possible links. If two cities are connected, prices will move in lockstep. So if there’s a spike in cocaine prices in the city of origin – or a source city, where the drug originates – that spike will be transmitted to all cities dependent upon that source. In addition, cocaine will flow from the city with the lower price to the city with the higher price. It takes a number of transactions for cocaine to reach its end price, and prices tend to go up as drugs move from one city to another, he said.

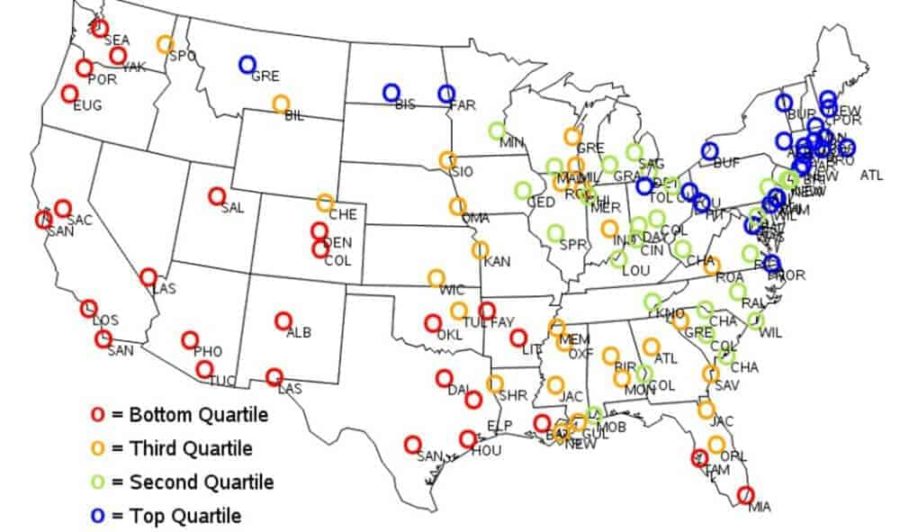

While cities in the north and northeast are destination cities for cocaine, Chandra found cities in the southern U.S. and along the west coast are source cities. In addition, cities in other regions, like Chicago and Atlanta, are major hubs for cocaine.

Chandra also created a map of possible drug routes, which he compared with a map produced by the National Drug Intelligence Center, and found that a number of his routes hadn’t been identified.

But Chandra cautions that his methodology shouldn’t be used in isolation. Instead, it is one piece of the larger drug trafficking puzzle. Individual bits of the publicly available NDIC data may or may not be accurate based on whether drug smugglers tell the truth. However, the combined data could lead to better drug enforcement.

Unfortunately, Chandra said, the NDIC was closed in 2012 and he’s not sure if another agency is continuing to collect data. But his research shows the importance of doing so.

“As an economist, the big takeaway is that prices carry some valuable information about trafficking in illegal goods,” Chandra said.

Two of Chandra’s former students, Samuel Peters and Nathaniel Zimmer, who recently graduated, assisted with the research. The study is published in the Journal of Drug Issues.