Are humans programmed to tell the truth? Not when lying is advantageous, says a new study led by Assistant Professor Ming Hsu at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. The report ties honesty to a region of the brain that exerts control over automatic impulses.

Hsu, who heads the Neuroeconomics Laboratory at the Haas School of Business and holds a joint appointment with the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, said the results, just published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, indicate that willpower is necessary for honesty when it is personally advantageous to lie.

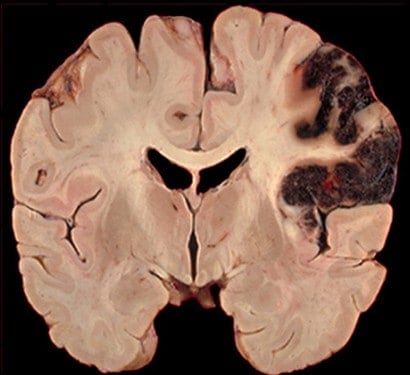

It is well-established that the brain’s dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is important for exerting control over impulses, but the role of this region in honesty and deception has been a matter of debate.

“So far, studies investigating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in honesty have primarily used correlational methods, like neuroimaging,” said study co-author Adrianna Jenkins of the Neuroeconomics Laboratory. “So it hasn’t been clear whether this region is involved in curbing honesty or enabling it.”

Hsu and his research team explored this question by studying three groups of patients: one with focal brain damage to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, one with damage to a different region of the brain and a control group with healthy brains. The groups otherwise generally matched each other in age and gender.

The groups engaged in two games. Both involved decisions about how much money to take for oneself or to give to an anonymous recipient, but only one game involved honesty.

In one game, participants simply chose one of two payment options to implement. For example, with options to take $10 and give $5 to another person or take $5 and give $10, the selfish move would be to choose the first option. The other game was identical except that, instead of choosing an option directly, the participant had to send a message to the other recipient stating “Option A is better for you” or “Option B is better for you.” The other person would then choose between the two options. In this game, the selfish move involved sending a dishonest message, misleading the other participant for personal gain.

In the game not involving honesty, the behavior of patients with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex damage was indistinguishable from that of the control groups. However, in the game involving honesty, the patients with damage in that region of the brain were more willing than the other groups to lie in order to benefit monetarily.

“The fact that dorsolateral prefrontal cortex patients were less able to implement honesty points to a causal role for DLPFC enabling honesty behavior,” Hsu explained. “And because DLPFC is known to be involved in control over automatic impulses, this suggests that being honest when it’s advantageous for you to lie requires control.”

Hsu noted that the study, using tools from cognitive neuroscience, behavioral economics and theoretical biology, has significant implications for understanding social interaction and cooperation within business organizations and beyond.

Hsu’s research team included Jenkins and Eric Set from the Neuroeconomics Laboratory, Donatella Scabini and Robert Knight from the Knight Laboratory in UC Berkeley’s psychology department and Pearl Chiu, Brooks King-Casas, and lead author Lusha Zhu from Virginia Tech’s Carilion Research Institute.