Microscopic particles that bind under low temperatures will melt as temperatures rise to moderate levels, but re-connect under hotter conditions, a team of New York University scientists has found. Their discovery points to new ways to create “smart materials,” cutting-edge materials that adapt to their environment by taking new forms, and to sharpen the detail of 3D printing.

“These findings show the potential to engineer the properties of materials using not only temperature, but also by employing a range of methods to manipulate the smallest of particles,” explains Lang Feng, the study’s lead author and an NYU doctoral student at the time it was conducted.

The research, which appears in the journal Nature Materials, reveals that the well-known Goldilocks Principle, which posits that success is found in the middle rather than at extremes, doesn’t necessarily apply to the smallest of particles.

The study focuses on polymers and colloids—particles as small as one-billionth and one-millionth of a meter in size, respectively.

These materials, and how they form, are of notable interest to scientists because they are the basis for an array of consumer products. For instance, colloidal dispersions comprise such everyday items as paint, milk, gelatin, glass, and porcelain and for advanced engineering such as steering light in photonics. By better understanding polymer and colloidal formation, scientists have the potential to harness these particles and create new and enhanced materials—possibilities that are now largely untapped or are in relatively rudimentary form.

In the Nature Materials study, the researchers examined polymers and larger colloidal crystals at temperatures ranging from room temperature to 85 degrees C.

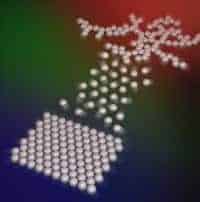

At room temperature, the polymers act as a gas bumping against the larger particles and applying a pressure that forces them together once the distance between the particles is too small to admit a polymer. In fact, the colloids form a crystal using this process known as the depletion interaction—an attractive entropic force, which is a dynamic that results from maximizing the random motion of the polymers and the range of space they have the freedom to explore.

As usual, the crystals melt on heating, but, unexpectedly, on heating further they re-solidify. The new solid is a Jello-like substance, with the polymers adhering to the colloids and gluing them together. This solid is much softer, more pliable and more open than the crystal.

This result, the researchers observe, reflects enthalpic attraction—the adhesive energy generated by the higher temperatures and stimulating bonding between the particles. By contrast, at the mid-level temperatures, conditions were too warm to accommodate entropic force, yet too cool to bring about enthalpic attraction.

Lang, now a senior researcher at ExxonMobil, observes that the finding may have potential in 3D printing. Currently, this technology can create 3D structures from two-dimensional layers. However, the resulting structures are relatively rudimentary in nature. By enhancing how particles are manipulated at the microscopic level, these machines could begin creating objects that are more detailed, and realistic, than is currently possible.