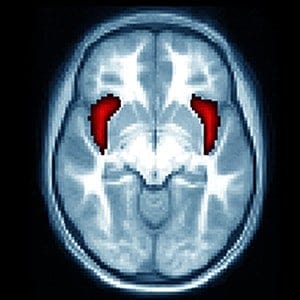

In school-age children previously diagnosed with depression as preschoolers, a key brain region involved in emotion is smaller than in their peers who were not depressed, scientists have shown.

The research, by a team at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, also suggests that the size of the brain’s right anterior insula may predict the risk of future bouts of depression, potentially giving researchers an anatomical marker to identify those at high risk for recurrence.

The study is published online Nov. 12 in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

There is one insula on each side of the brain, and they are thought to be involved in emotion, perception, self-awareness and cognitive function.

The insula also is smaller in depressed adults compared with those of their peers who are not depressed. By using MRI scans and focusing on brain anatomy, the researchers hope to find clues to better diagnose and treat depression and to identify individuals at higher risk for recurrent episodes.

As part of the study, the investigators also found the same brain structure is smaller in kids diagnosed with pathological guilt during their preschool years, providing evidence that excessive guilt is a symptom of depression related to the size of the insula.

“That’s not a complete surprise because for many years now, excessive guilt has consistently been a predictor of depression and a major outcome related to being depressed,” said first author Andrew C. Belden, PhD.

Pathological guilt can be a symptom of clinical depression, as well as other psychiatric disorders including anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder. Belden, an assistant professor of child psychiatry, said it’s relatively easy to spot the problem in children because they excessively blame themselves for things they’ve done — and haven’t done.

“A child with pathological guilt can walk into a room and see a broken lamp, for example, and even if the child didn’t break it, he or she will start apologizing,” Belden explained. “Even after being told he or she is not at fault, the child will continue to apologize and feel bad.”

The “million-dollar question,” he said, is whether depressed children become more prone to guilt or guilt-prone children are more likely to become depressed. Either way, Belden said, the discovery that pathological guilt is related to changes in the brain that increase the risk for recurrent depression could be a major step in better understanding the trajectory of depression.

The researchers followed a group of children in the Preschool Depression Study, conducted by investigators led by Joan L. Luby, MD, director of Washington University School of Medicine’s Early Emotional Development Program. The children were assessed for depression and guilt each year from ages 3-6.

There were 47 diagnosed with depression as preschoolers, and 82 who had not been depressed. Some 55 percent of those with depression had displayed pathological guilt as preschoolers, while 20 percent of the nondepressed group had excessive guilt.

All of the children also had MRI brain scans about every 18 months from ages 7-13.

The researchers found that children with a smaller insula in the right hemisphere of the brain — related either to depression or excessive guilt — were more likely to have recurrent episodes of clinical depression as they got older.

“Arguably, our findings would suggest that guilt early in life predicts insula shrinkage,” Belden said. “I think the story is beginning to emerge that depression may predict changes in the brain, and these brain changes predict risk for recurrence.”

The research suggests that excessive guilt and depression may put preschoolers on a developmental trajectory that contributes to problems with depression later in childhood and even throughout life. Some children experience depression, recover and never have another episode, but others experience a chronic and relapsing course. Belden said it is important to identify those who are at risk for chronic and relapsing depression.

A previous study from the same group found that children diagnosed with depression as preschoolers were 2.5 times more likely to be clinically depressed in elementary and middle school than kids who were not depressed in preschool.

The research team would like to continue the study for at least five more years. During that time frame, study subjects will pass through the high-risk period of adolescence.

“We’re hoping to follow these children for several more years, perhaps even into adulthood,” Belden said. “On the immediate horizon is a look at the effects of some things that become more common during adolescent years as kids hit a high-risk time for substance and alcohol abuse and other problems that often co-exist with clinical depression. We want to see how those sorts of issues affect these children we’ve been following since preschool.”