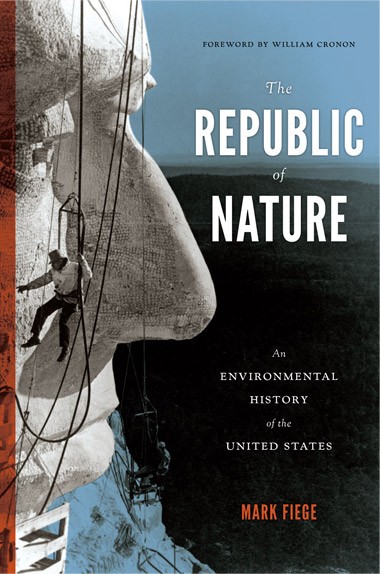

BOOK REVIEW: Fiege, Mark. Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012.

It’s a strange day when a book arrives in your mailbox to review and on the back are laudatory quotations from scholarly giants William Cronon and Richard White. Snagging one of these guys is the equivalent to scoring over a million points in Donkey Kong. Getting both is like achieving the latter upside down. It just doesn’t happen.

So I was excited to crack open Mark Fiege’s Republic of Nature and see what it had to offer. I’m technically not an environmental historian, but alot of the stuff I get to read and write about intersects with notions about the natural and landscape. But this book has it’s own website. Which is kind of a Big Deal.

The short version of this review is Fiege nails it. Absolutely nails it. For the long version, read onward–

The best examples of historical scholarship usually do one of two things: either they open up, in dramatic fashion, new areas of exploration via methodological tools or theoretical frameworks, or they cut across the bounds of time and the scores of texts which the history profession produces to synthesize scholarship and show that what we thought was many was actually one. Mark Fiege accomplishes the latter of these in The Republic of Nature.

The best examples of historical scholarship usually do one of two things: either they open up, in dramatic fashion, new areas of exploration via methodological tools or theoretical frameworks, or they cut across the bounds of time and the scores of texts which the history profession produces to synthesize scholarship and show that what we thought was many was actually one. Mark Fiege accomplishes the latter of these in The Republic of Nature.

This is, as the author acknowledges from the outset, something of a peculiar book. It does not propose to be a radical or alternate history, refuting the claims of previous surveys of American history. And yet the narrative it weaves uncovers a tapestry of experiences and interconnections that will be striking and new to most. Indeed, it is not a comprehensive survey at all, but instead chooses nine moments of experience in American life, from the Salem witch trials, to the American Revolution, King Cotton, Abraham Lincoln, the Battle of Gettysburg, the transcontinental railroad, the Manhattan project, Brown v. Board of Education, and the oil crisis of 1973-4, to excavate the place of environment and relocate it from the borders of American history to its center.

Chapters 3 (King Cotton), 5 (Gettysburg), 7 (the Manhattan Project), and 8 (Brown v. Board) are the strongest of the book. Of these, I was most pleasantly surprised by the latter two. Throughout, Fiege marshals an impressive understanding of the secondary literature, supplemented by select primary sources, to delve into the rhizomatic. Collectively, these chapters demonstrate best what seems obvious by the end of the study: that American history is environmental history. The individual human experience remains ineluctably rooted in the demographic, the topographical, the geological, the biological, and the ecological. The cycles that govern nature equally govern human lives—work and play, love and hate, life and death. The forces that shape, equally, the countryside and the city, also influence profoundly human industry, politics, conflict, interaction, and scientific and technological inquiry. Fortunes wax and wane interchangeably according to the degree with which the natural is transported, transformed, and traversed.

To single the above out is not to suggest the rest of the text falls short. Indeed, there are moments in the chapters below that will, even to seasoned scholars, offer novel interpretations useful in constructing with more fidelity the penumbra of experience in American life. Chapter 2 (By the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God) remains the weakest, locating republican fervor in the shift from divine law to natural law and presenting the opportunity for revolution at the same time it portended trouble down the road for slavery. Fiege’s analytical framework seems the most stretched here, and has trouble accounting for the totality of experience with little information presented that does not already exist elsewhere. Chapter 4 (Nature’s Nobleman) is somewhat less thin, locating the inception and maturation of Lincoln’s particular antislavery ideology in his formative experiences as a child and young man working the land and coming up against the harsh realities of free market labor. In places, it struggles to connect this experience with the political expediencies of war and the decisions that they necessitated. Other chapters, like the first (Satan in the Land), do not suffer from analytical flaws but rather see somewhat more compelling treatment elsewhere (in this case David Hall’s Worlds of Wonder (1989)).

That this review enumerates these fuzzier moments in The Republic of Nature should emphatically not to suggest to potential readers that Fiege’s narrative is one worth passing over. Indeed the opposite—the above moments merely shine slightly less in a study that is as a whole a stunning and beautifully treated reconceptualization of the those moments in American history which survey courses have taught us to dread.

Ry Marcattilio-McCracken has a PhD in the history of science, technology, and medicine. He writes at slowloris.scienceblog.com, slowlorisblog.wordpress.com and tweets @slowlorisblog.