Super-hydrophobic properties could lead to applications in solar panels, sanitation and as rust-free metals

Scientists at the University of Rochester have used lasers to transform metals into extremely water repellent, or super-hydrophobic, materials without the need for temporary coatings.

Super-hydrophobic materials are desirable for a number of applications such as rust prevention, anti-icing, or even in sanitation uses. However, as Rochester’s Chunlei Guo explains, most current hydrophobic materials rely on chemical coatings.

In a paper published today in the Journal of Applied Physics, Guo and his colleague at the University’s Institute of Optics, Anatoliy Vorobyev, describe a powerful and precise laser-patterning technique that creates an intricate pattern of micro- and nanoscale structures to give the metals their new properties. This work builds on earlier research by the team in which they used a similar laser-patterning technique that turned metals black. Guo states that using this technique they can create multifunctional surfaces that are not only super-hydrophobic but also highly-absorbent optically.

Guo adds that one of the big advantages of his team’s process is that “the structures created by our laser on the metals are intrinsically part of the material surface.” That means they won’t rub off. And it is these patterns that make the metals repel water.

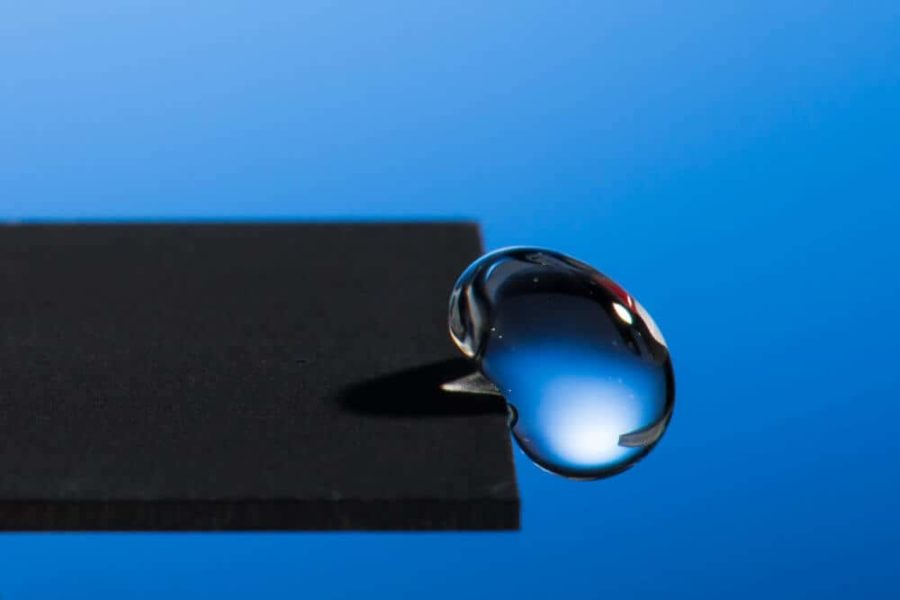

“The material is so strongly water-repellent, the water actually gets bounced off. Then it lands on the surface again, gets bounced off again, and then it will just roll off from the surface,” said Guo, professor of optics at the University of Rochester. That whole process takes less than a second.

The materials Guo has created are much more slippery than Teflon—a common hydrophobic material that often coats nonstick frying pans. Unlike Guo’s laser-treated metals, the Teflon kitchen tools are not super-hydrophobic. The difference is that to make water to roll-off a Teflon coated material, you need to tilt the surface to nearly a 70-degree angle before the water begins to slide off. You can make water roll off Guo’s metals by tilting them less than five degrees.

As the water bounces off the super-hydrophobic surfaces, it also collects dust particles and takes them along for the ride. To test this self-cleaning property, Guo and his team took ordinary dust from a vacuum cleaner and dumped it onto the treated surface. Roughly half of the dust particles were removed with just three drops of water. It took only a dozen drops to leave the surface spotless. Better yet, it remains completely dry.

Guo is excited by potential applications of super-hydrophobic materials in developing countries. It is this potential that has piqued the interest of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has supported the work.

“In these regions, collecting rain water is vital and using super-hydrophobic materials could increase the efficiency without the need to use large funnels with high-pitched angles to prevent water from sticking to the surface,” says Guo. “A second application could be creating latrines that are cleaner and healthier to use.”

Latrines are a challenge to keep clean in places with little water. By incorporating super-hydrophobic materials, a latrine could remain clean without the need for water flushing.

But challenges still remain to be addressed before these applications can become a reality, Guo states. It currently takes an hour to pattern a 1 inch by 1 inch metal sample, and scaling up this process would be necessary before it can be deployed in developing countries. The researchers are also looking into ways of applying the technique to other, non-metal materials.

Guo and Vorobyev use extremely powerful, but ultra-short, laser pulses to change the surface of the metals. A femtosecond laser pulse lasts on the order of a quadrillionth of a second but reaches a peak power equivalent to that of the entire power grid of North America during its short burst.

Guo is keen to stress that this same technique can give rise to multifunctional metals. Metals are naturally excellent reflectors of light. That’s why they appear to have a shiny luster. Turning them black can therefore make them very efficient at absorbing light. The combination of light-absorbing properties with making metals water repellent could lead to more efficient solar absorbers – solar absorbers that don’t rust and do not need much cleaning.

Guo’s team had previously blasted materials with the lasers and turned them hydrophilic, meaning they attract water. In fact, the materials were so hydrophilic that putting them in contact with a drop of water made water run “uphill.”

Guo’s team is now planning on focusing on increasing the speed of patterning the surfaces with the laser, as well as studying how to expand this technique to other materials such as semiconductors or dielectrics, opening up the possibility of water repellent electronics.

Funding was provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United States Air Force Office of Scientific Research. The article, “Multifunctional surfaces produced by femtosecond laser pulses,” was published in the Journal of Applied Physics on January 20, 2015 (DOI: 10.1063/1.4905616). It can be accessed at: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/jap/117/3/10.1063/1.4905616

This technique has great possibilities for marine and aeronautical applications too. Consider a ship or an aircraft whose outer surface has been treated by this technique. It would not become “wetted” by the passing fluid (water or air). This means that the drag due to the normally developed laminar and turbulent boundary layers would simply not exist, with a huge reduction in power needed to drive the vehicle forward.

Another possible use would be in creating surfaces that cannot become damaged due to metal structures fatigue initiation. Fatigue cracks form from almost nothing due to small faults in the crystal surface associated with corrosion. With no corrosion, the cracks cannot get started.