Family income is associated with children’s brain structure, reports a new study in Nature Neuroscience coauthored by Teachers College faculty member Kimberly Noble. The association appears to be strongest among children from lower-income families.

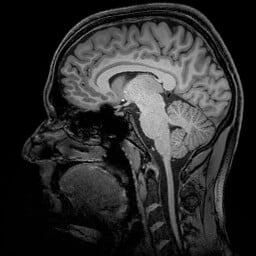

In a sample of more than 1,000 typically developing children and adolescents between three and 20 years old, a group led by Noble and Elizabeth Sowell, Professor of Pediatrics at The Saban Research Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, found that increases in both parental education and family income were associated with increases in the surface area of numerous brain regions, including those implicated in language and executive functions. Family income appeared to have a stronger, positive relationship with brain surface area than parental education.

“We can’t say if the brain and cognitive differences we observed are causally linked to income disparities,” said Noble, who currently is both a TC Visiting Professor and Director of the Neurocognition, Early Experience and Development Lab of Columbia University Medical Center, but will join TC’s faculty as Associate professor of Neuroscience and Education in July in the Department of Biobehavioral Sciences. “But if so, policies that target poorest families would have the largest impact on brain development.”

The results do not imply that a child’s future cognitive or brain development is predetermined by socioeconomic circumstances, the researchers said.

Noble said that among children from the lowest-income families, small differences in income were associated with relatively large differences in surface area in a number of regions of the brain associated with skills important for academic success. Conversely, among children from higher-income families, incremental increases in income level were associated with much smaller differences in surface area. Higher income was also associated with better performance in certain cognitive skills – cognitive differences that could be accounted for, in part, by greater brain surface area.

In the study, titled “Family Income, Parental Education and Brain Structure in Children and Adolescents,” the researchers, who were investigating the relationships between brain structure, family income, and parental education, controlled for potential differences in brain structure related to ancestral origin by collecting DNA samples from each participant.

“Family income is linked to factors such as nutrition, health care, schools, play areas and, sometimes, air quality,” said Sowell, adding that everything going on in the environment shapes the developing brain. “Future research may address the question of whether changing a child’s environment – for instance, through social policies aimed at reducing family poverty – could change the trajectory of brain development and cognition for the better.”

In fact, Noble and a team of esteemed social scientists and neuroscientists have already embarked on precisely that line of inquiry. They are in the midst of a pilot study in which mothers are given large or small monthly income payments for the first three years after their children are born. Ultimately they hope to recruit 1,000 mothers, half of whom would receive $4,000 per year ($333 per month), and half of whom would receive just $240 per year ($20 per month), a difference that is on par with the amount of the earned income tax credit.

“We’ll be looking at brain function and cognitive ability at age 3, using cognitive assessments, social and emotional development tests and brain function as measured by electroencephalography and event-related potentials,” Noble says. “If the children of mothers receiving larger payments show beneficial effects on brain function, it would be a step toward refuting the argument that poverty is a symptom, not a cause, and that wealthier parents are wealthy because they possess — and pass on — traits of self-discipline, determination and resilience. By identifying how income affects early child development, we hope to inform anti-poverty policies that better support children’s well-being.”

it is more often that those children from low income families are mostly the ones succeeding in life because they are motivated to change the way their families live and do better for their communities. Poverty really shapes people’s brain. Children from high income families do not have so much worry about how to change their family’s situation because there is nothing to change, since most of them have almost everything they need.

The biological activity including BRAIN SIZE being determined by genes but influenced by environment is it not the other environmental factors influence the individual? Air quality is one used in the parameters. Have they further tried breaking up those?

How is that the parental education has no effect of the child’s brain? I mean i know that it doesnt mean that if a parent is intelligent it is genetically passed on to the child. Yet I somehow believe that family income might increase the brain size, this is because most of the kids that are from less privileged homes with poor incomes are greatly motivated to work harder and succed in life. Well even though children from higher income families have a smaller surface area in there brain, they also perform better at other skills, which is great. What are cognitive skills?

I don’t believe it. There are many examples of people from poor backgrounds and poverty-struck families who have done well. It is not a genetic caused problem but one of upbringing alone, that allows the curse of poverty to pass on. Lack of ability to receive a good education must be stopped and equal opportunity permitted.