It’s a photo published routinely: a bomb blast that’s left a mass of crumbled concrete, twisted steel, splintered wood and, often, victims.

But it’s amid this chaos that explosives experts pore through minute fragments for clues to “the who and the how” of the bomb.

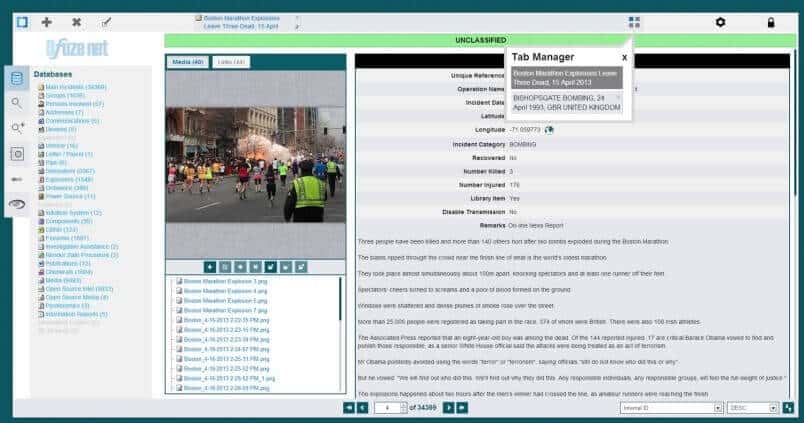

One of the tools aiding a growing number of bomb investigators attempting to solve these cases is software called Dfuze, a global database that stores millions of points of visual and textual data about every aspect of bombs, bomb-makers and the destruction they leave behind.

The system connects agencies in about 25 countries in Europe, Asia and Africa.

Dfuze was born about a decade ago at the Bomb Data Center in London’s New Scotland Yard, according to Neil Fretwell, the former lead investigator at the center who is currently employed by Intelligent Software Solutions, which now owns the software.

Fretwell specialized in post-blast forensics of terror bombings.

“We were quite busy because I was there in the ’80s and ’90s during the Irish Troubles,” he said, referring to the decades of conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland.

“We had literally tens of thousands, almost hundreds of thousands, of old paper records going back years,” he said.

About 12 years ago, Scotland Yard asked a software company to build a database of archived records, which was done in conjunction with the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms.

“I worked on the 15th floor, and there was something like eight or nine different computer systems operating on that floor of the building,” Fretwell said. “Within the whole of the anti-terrorist project there were about 90 computer systems operating.”

The shortcomings of that uncoordinated “system” gobsmacked Fretwell in the wake of the worst bombing in Great Britain in a generation on July 7, 2005, when four Islamist extremists detonated four bombs in subway trains and a bus in London. The country’s first suicide bombings, the blasts killed 52 people and the four bombers.

Fretwell was investigating one of the bomb scenes, digging through for clues.

“It was really important to get imagery of what I was classifying as components — or what I thought were components — of explosive devices back to my office so that they could start conducting research on the components, to work out who manufactured it, who distributed it,” he said.

“The only way we had at the time to do that was to literally take photographs, load them through a laptop to a CD and then stick them on the back of a motorbike and send them back to Scotland Yard, which struck me as so antiquated.”

The Dfuze system replaced all those legacy databases and incorporated the digitalized paper records — with each item converted into optical character recognition data when possible, making every detail searchable. The system allowed investigators in the field to continue contributing photos, video and text in an encrypted but easily transmitted format.

“It was an info-sharing technology where I could download an encrypted file from my system, send it electronically to the States,” he said. “They could take it off an open Internet link because it was encrypted, put it into their system, press a button, and it would automatically populate their database.

“When you have multiple [bombing] scenes, it’s important to get information not only back to the center, but to get it to all the other scenes you think are linked so that they have the information as well,” Fretwell said. “If you find something at your scene, it’s all well and good for command and control to know about it, but you also want everyone else who may be looking for similar components to have that same information as well.”

The ATF uses Dfuze to search archived records of reports by manufacturers of lost or stolen explosives, which have serial numbers and other identifying marks.

“For example, explosives that a manufacturer may have lost or had stolen 20 or 30 years ago, we may have records of it,” said Hector Munoz-Navarro, an ATF intelligence research specialist. “What Dfuze allows us to do is go back and quickly look through those records in a digital storehouse and provide that information so we can possibly tie it into the recovery of stolen goods.”

Munoz-Navarro declined to talk about how Dfuze has supported specific explosives investigations at ATF. But he likened Dfuze to using Google to search, say, the word “explosives,” for which the search engine might return as results everything from a Wikipedia entry to a university involved in studies of explosives.

The Dfuze search would find disparate data possibly related to the investigation at hand and “would tie us into events that may have happened here in the United States or overseas, because we also like to use the information we received from our partners,” Munoz-Navarro said.

Among the countries in which agencies use Dfuze are Australia, Singapore, Kenya, Morocco, Canada, Norway and the Netherlands, as well as China’s Hong Kong.

Dfuze is particularly useful in correlating information about the methods and preferences of bombers, known as a “signature.”

“Bomb-makers are creatures of habit, and they go down the route of using exactly the same components,” Fretwell said. “If they’ve made a device and it went off successfully, they’ll use the same components over and over again. So you can build up a picture of the bomb-maker through the types of components he’s used, even down to using, say, a yellow, blue and red wire — even though it didn’t matter what color they would use. But since they used that in the past, they would always use it.”

For example, a favored component of Irish Republican Army bombers was the Memopark Swiss timer, a gadget legitimately used to remind drivers that time had expired on a parking meter. A Northern Ireland priest located a novelty shop in Zurich and bought out the entire stock of 400 Memopark timers, and they were traced to scores of bombings in Great Britain.

“We knew from the very early stages that if you found any signs of this timer, you knew it was an Irish-inspired attack,” Fretwell said. “That became very useful when there was an upsurge in Islamic bombers. It was very important to know which groups you were looking for, and we were easily able to.”

One of the newest twists on the software is Dfuze Predict, which attempts to crunch the database with other data, such as weather reports, current events, insurance statistics and ticket sales.

An early version of the software was used for the 2012 Olympics in London to identify likely sites for an attack, which were then “target-hardened,” he said.

And then … nothing happened.

“So it’s very difficult to know if you’ve been successful or not,” Fretwell said with a chuckle. “You have to suppose in the grand scheme of things you have been successful because there hasn’t been an attack but, unfortunately, you’ll never know if it was because of the extra security or the attack wasn’t going to take place in the first place.”