A team of marine researchers funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) has discovered a three-way conflict raging at the microscopic level in the frigid waters off Antarctica over natural resources such as vitamins and iron.

The competition has important implications for understanding the fundamental workings of globally significant food webs of the Southern Ocean, home to such iconic Antarctic creatures as penguins, seals, and orcas.

At the base of that food web are phytoplankton, single-celled organisms that survive by turning sunlight into food sources such as sugars and carbohydrates. Oceanographers have long recognized that iron fertilization in the Southern Ocean will drive phytoplankton blooms.

According to Andrew Allen, the senior author on the paper, the new research indicates that particular groups of bacteria, perhaps specifically cultivated by phytoplankton, are also important for regulating the magnitude of phytoplankton blooms. The bacteria also help sustain the phytoplankton by supplying them with vitamin B12.

Allen is jointly affiliated with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) at the University of California, San Diego, and the Maryland-based J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI).

The new findings, which were supported in part by an awardfrom the Division of Polar Programs in NSF’s Geosciences Directorate as well as by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, may also be key to understanding how the vastly productive polar ecosystem might respond to future change caused by warming of the oceans.

The research was published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Phytoplankton and bacteria form the base of the marine food web. The Southern Ocean encircling Antarctica is home to massive phytoplankton populations, and scientists have long considered their growth to be controlled primarily by the availability of iron and light.

“Through a combination of field experiments and sequencing, we have obtained a new view of the microbial interactions underpinning a highly productive ecosystem,” said Allen.

The new research also may cause biologists to examine long-standing assumptions about the ecological balance of microbial communities in the Southern Ocean.

“I think this study also illustrates the eye-opening sensitivity of marine phytoplankton and bacteria to very minor additions of scarce micro-nutrients over very short–hourly–time scales,” said Erin Bertrand, a former JCVI and SIO researcher and Division of Polar Programs’ post-doctoral fellow, who is now an assistant professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Bertrand, the lead author of the study added that “this suggests that these marine ecosystems are naturally poised to respond swiftly to changes in availability of these nutrients. It’s likely that these states of resource boom and bust are a common, perhaps critical, feature of this remote environment.”

With this new understanding of the nature of the interactions between microorganisms in the polar ocean and the careful balance of competitive and cooperative behaviors that exist in this key ecosystem, Allen noted, researchers can work towards predicting how these relationships might change in the future.

The team’s findings are based on research supported by the U.S. Antarctic Program in and around McMurdo Station, the largest year-round research station in Antarctica. NSF manages the U.S. Antarctic Program.

Flying aboard helicopters based at McMurdo, the research team ventured out to the edge of the sea ice in McMurdo sound, where they carefully collected water samples from the sunlit surface and returned them to the Albert P. Science and Engineering Center at McMurdo, in order to perform experiments.

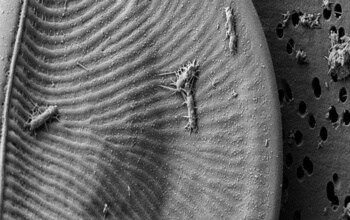

The researchers learned that although the water appeared teeming with a particular type of phytoplankton, called diatoms, the diatoms were malnourished.

Unlike most regions of the global ocean which do not contain sufficient nitrogen or phosphorous for sustained phytoplankton growth, diatoms in the remote waters of McMurdo Sound were starving from lack of iron and deficiency of vitamin B12.

“Just like humans, phytoplankton require vitamins, including vitamin B12, to survive,” said Bertrand.

She added, “We’ve shown that the phytoplankton in McMurdo Sound acquire this precious resource from a very specific group of bacteria. Those bacteria, in turn, appear to depend directly on phytoplankton to supply them with food and energy.”

Results of the study, however, suggest that here is where it gets messy.

A different group of bacteria, also relying on the phytoplankton for food and energy, appear to compete with the diatoms for the precious vitamin, and all three groups of microbes are competing for iron, which, due to the extreme remoteness of the Southern Ocean, is a scarce and consequently invaluable resource.

The result, the researchers said, is a new picture of a precariously balanced system, full of microbial drama over the competiton for survival.

The team further confirmed that a large portion of the B12 supply in the Southern Ocean appears to be produced by a particular group of bacteria belonging to the Oceanospirllaceae. This aspect of this study was facilitated by collaboration with researchers at the University of Rhode Island (URI) and the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass. which have been conducting studies on bacteria in and around the Amundsen Sea, another region of the Southern Ocean.