The boiling of water is at the heart of many industrial processes, from the operation of electric power plants to chemical processing and desalination. But the details of what happens on a hot surface as water boils have been poorly understood, so unexpected hotspots can sometimes melt expensive equipment and disable plants.

Now researchers at MIT have developed an understanding of what causes this extreme heating — which occurs when a value known as the critical heat flux (CHF) is exceeded — and how to prevent it. The new insights could make it possible to operate power plants at higher temperatures and thus significantly higher overall efficiency, they say.

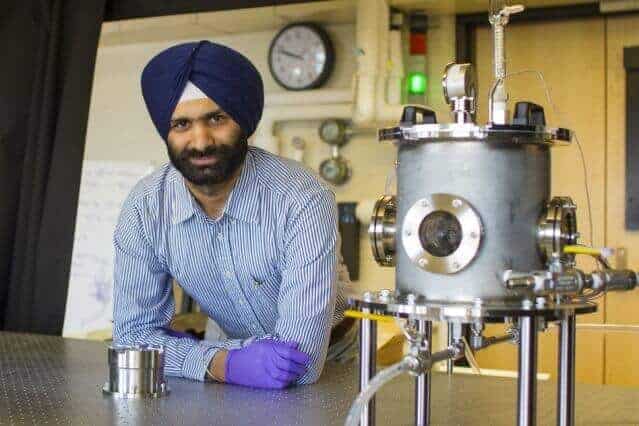

The findings are reported this week in the journal Nature Communications, in a paper co-authored by mechanical engineering postdoc Navdeep Singh Dhillon, professor of nuclear science and engineering Jacopo Buongiorno, and associate professor of mechanical engineering Kripa Varanasi.

“Roughly 85 percent of the worldwide installed base of electricity relies on steam power generators, and in the U.S. it’s 90 percent,” Varanasi says. “If you’re able to improve the boiling process that produces this steam, you can improve the overall power plant efficiency.”

The bubbles of vapor that characterize boiling, familiar to anyone who has ever boiled water on a stove, turn out to limit energy efficiency. That’s because gas — whether it’s air or water vapor — is highly insulating, whereas water is a good absorber of heat. So on a hot surface, the more area that is covered with bubbles, the less efficient the transfer of heat energy becomes.

If those bubbles persist too long at a given spot, it can significantly increase the temperature of the metal underneath, since heat is not transferred away fast enough, Varanasi says — and can potentially melt part of the metal.

“This will most certainly damage an industrial boiler, a potentially catastrophic scenario for a nuclear power plant or a chemical processing unit,” says Dhillon. When a layer of bubbles limits heat transfer, “locally, the temperature can increase by several thousand degrees” — a phenomenon known as a “boiling crisis.”

The boiling of water is at the heart of many industrial processes, from the operation of electric power plants to chemical processing and desalination. But the details of what happens on a hot surface as water boils have been poorly understood, so unexpected hotspots can sometimes melt expensive equipment and disable plants.

Now researchers at MIT have developed an understanding of what causes this extreme heating — which occurs when a value known as the critical heat flux (CHF) is exceeded — and how to prevent it. The new insights could make it possible to operate power plants at higher temperatures and thus significantly higher overall efficiency, they say.

The findings are reported this week in the journal Nature Communications, in a paper co-authored by mechanical engineering postdoc Navdeep Singh Dhillon, professor of nuclear science and engineering Jacopo Buongiorno, and associate professor of mechanical engineering Kripa Varanasi.

“Roughly 85 percent of the worldwide installed base of electricity relies on steam power generators, and in the U.S. it’s 90 percent,” Varanasi says. “If you’re able to improve the boiling process that produces this steam, you can improve the overall power plant efficiency.”

The bubbles of vapor that characterize boiling, familiar to anyone who has ever boiled water on a stove, turn out to limit energy efficiency. That’s because gas — whether it’s air or water vapor — is highly insulating, whereas water is a good absorber of heat. So on a hot surface, the more area that is covered with bubbles, the less efficient the transfer of heat energy becomes.

If those bubbles persist too long at a given spot, it can significantly increase the temperature of the metal underneath, since heat is not transferred away fast enough, Varanasi says — and can potentially melt part of the metal.

“This will most certainly damage an industrial boiler, a potentially catastrophic scenario for a nuclear power plant or a chemical processing unit,” says Dhillon. When a layer of bubbles limits heat transfer, “locally, the temperature can increase by several thousand degrees” — a phenomenon known as a “boiling crisis.”

To avoid exceeding the CHF, power plants are usually operated at temperatures lower than they otherwise could, limiting their efficiency and power output. Using textured surfaces has been known to help, but it has not been known why, or what the optimal texturing might be.

Contrary to prevailing views, the new work shows that more texturing is not always better. The MIT team’s experiments, which use simultaneous high-speed optical and infrared imaging of the boiling process, show a maximum benefit at a certain level of surface texturing; understanding exactly where this maximum value lies and the physics behind it is key to improving boiler systems, the team says.

“What was really missing was an understanding of the specific mechanism that textured surfaces would provide,” Buongiorno says. The new research points to the importance of a balance between capillary forces and viscous forces in the liquid.

“As the bubble begins to depart the surface, the surrounding liquid needs to rewet the surface before the temperature of the hot dry spot underneath the bubble exceeds a critical value,” Varanasi says. This requires understanding the coupling between liquid flow in the surface textures and its thermal interaction with the underlying surface.

“If anything can enhance the heat transfer, that could improve the operating margin of a power plant,” Varanasi says, allowing it to operate safely at higher temperatures.

By improving the overall efficiency of a plant, it’s possible to reduce its emissions: “You can get the same amount of steam production from a smaller amount of fuel,” Dhillon says. At the same time, the plant’s safety is improved by reducing the risk of overheating, and catastrophic boiler failures.

“This research uses a unique combination of precision micro- [and] nanofabrication, probative experimental techniques, and innovative analysis to investigate the existence of an optimal surface geometry,” says Matthew McCarthy, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Drexel University who was not involved in this research. “While numerous researchers have shown that structured coatings can enhance CHF, work like this is critical to answering why, and more importantly, answers questions on how to optimize surfaces for increased performance.”

The research was supported by Chevron Corp., the Kuwait-MIT Center for Natural Resources and the Environment, and a Shapiro fellowship from Mechanical Engineering Department. The micro-nano structured surfaces used in the study were fabricated in the Microsystems Technologies Labrotary (MTL) and at Harvard CNS.