Having a light touch can make a hefty difference in how well animals and robots move across challenging granular surfaces such as snow, sand and leaf litter. Research reported October 9 in the journal Bioinspiration & Biomimetics shows how the design of appendages – whether legs or wheels – affects the ability of both robots and animals to cross weak and flowing surfaces.

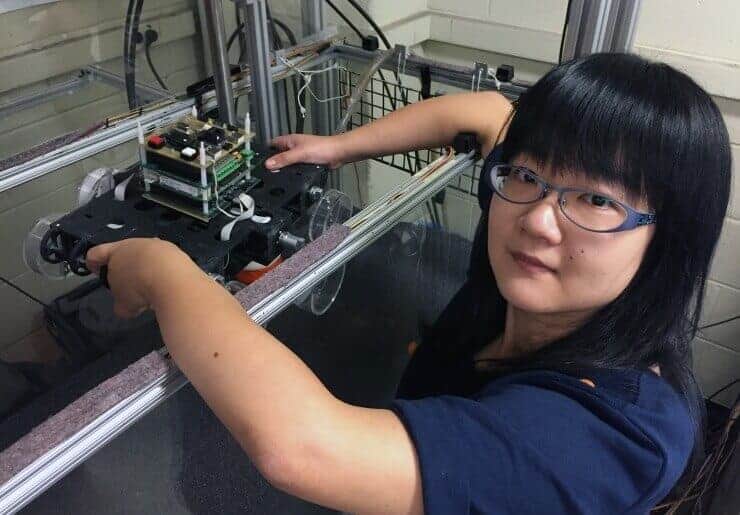

Using an air fluidized bed trackway filled with poppy seeds or glass spheres, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology systematically varied the stiffness of the ground to mimic everything from hard-packed sand to powdery snow. By studying how running lizards, geckos, crabs – and a robot – moved through these varying surfaces, they were able to correlate variables such as appendage design with performance across the range of surfaces.

The key measure turned out to be how far legs or wheels penetrated into the surface. What the scientists learned from this systematic study might help future robots avoid getting stuck in loose soil on some distant planet.

“You need to know systematically how ground properties affect your performance with wheel shape or leg shape, so you can rationally predict how well your robot will be able to move on the surfaces where you have to travel,” said Dan Goldman, a professor in the Georgia Tech School of Physics. “When the ground gets weak, certain animals seem to still be able to move around independently of the surface properties. We want to understand why.”

The research was supported by National Science Foundation, Army Research Laboratory and Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

For years, Goldman and colleagues have been using trackways filled with granular media to study the locomotion of animals and robots, but in the past, they had used fluidized bed only to set the initial compaction of the media. In this study, however, they used variations in continuous air flow – introduced through the bottom of the device – to vary the substrate’s resistance to penetration by a leg or wheel.

Goldman compares the trackway to the wind tunnels used for aerodynamic studies.

“By varying the air flow, we can create ground that is very, very weak – so that you sink into it quite easily, like powdery snow, and we can have ground that is very strong, like sand,” he explained. “This gives us the ability to study the mechanism by which animals and robots either succeed or fail.”

Using a bio-inspired hexapedal robot known as Sandbot as a physical model, the researchers studied average forward speed as a factor of ground penetration resistance – the “stiffness” of the sand – and the frequency of leg movement. The average speed of the robot declined as the increased air flow through the trackway made the surface weaker. Increasing the leg frequency makes the speed decrease more rapidly with increasing air flow.

The five animals – with different body plans and appendage features – all did better than the robot, with the best performer being a lizard collected in a California desert. The speed of theC. draconoides wasn’t slowed at all as the surface became easier to penetrate, while other animals saw performance losses of between 20 and 50 percent on the loosening surfaces.

“We think that this particular lizard is well suited to the variety of terrain because it has these ridiculously long feet and toes,” Goldman said. “These feet and toes really enable it to maintain high performance and reduce its penetration into the surface over a wide range of substrate conditions. On the other hand, we see animals like ghost crabs that experience a tremendous loss of performance as the substrate changes, something that was surprising to us.”

The robot lost 70 percent of its speed even with wheels designed to lighten its pressure on the surface.

Skiers and beachcombers can certainly understand why. As the surface becomes easier for a ski or foot to penetrate, more energy is required to move and forward progress slows. Human and skiers haven’t evolved solutions to that problem, but desert-dwelling creatures have. The research, Goldman says, will help us understand how they do it.

“The magic for us is how the animals are so good at this,” he said. “There’s a clear practical application to this. If you can get the controls and morphology right, you could have a robot that could move anywhere, but you have to know what you are doing under different conditions.”

As part of the research, Georgia Tech graduate students Feifei Qian and Tingnan Zhang used a terradynamics approach based on resistive force theory to perform numerical simulations of the robots and animals. They found that their model successfully predicted locomotor performance for low resistance granular states.

“This work expands the general applicability of our resistive force theory of terradynamics,” said Goldman. “The resistive force theory, which allows us to compute forces on limbs intruding into the ground, continues to work even in situations where we didn’t think it would work. It expands the applicability of terradynamics to even weaker states of material.”

In addition to those already mentioned, co-authors include Wyatt Korff from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Virginia, Paul Umbanhowar from Northwest University, and Robert Full from the University of California at Berkeley.

CITATION: Feifei Qian, et al., “Principles of appendage design in robots and animals determining terradynamic performance on flowable ground,” (Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-3190/10/5/056014