We all love our sugar, especially during the holidays. Cookies, cake, and candy are simply irresistible.

While sugar cravings are common, the physiological mechanisms that trigger our “sweet tooth” are not well defined.

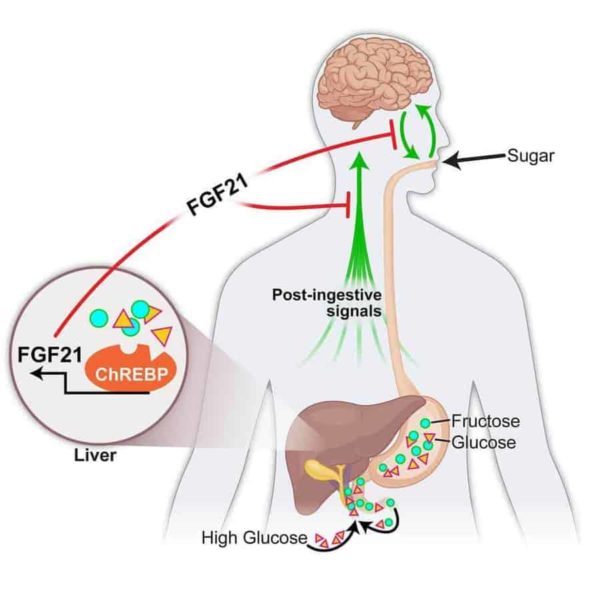

A University of Iowa-led study in mice shows that a hormone produced by the liver, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), suppresses the consumption of simple sugars. The researchers report that FGF21 is produced in the liver in response to high carbohydrate levels. FGF21 then enters the bloodstream, where it sends a signal to the brain to suppress the preference for sweets.

“This is the first liver-derived hormone we know that regulates sugar intake specifically,” says Matthew Potthoff, assistant professor of pharmacology in the UI Carver College of Medicine. Potthoff is co-senior author on the paper, published online in the journal Cell Metabolism, with Matthew Gillum, professor at the University of Copenhagen (Denmark).

Previous research explains how certain hormones affect appetite; however, these hormones do not regulate any specific macronutrient (carbohydrate, protein, fat) and are produced by organs other than the liver.

The research could improve diets and help patients who are diabetic or obese.

“We’ve known for a while that FGF21 can enhance insulin sensitivity,” says Lucas BonDurant, a doctoral student in the Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Molecular and Cellular Biology and co-first author in the study. “Now, there’s this dimension where FGF21 can help people who might not be able to sense when they’ve had enough sugar, which may contribute to diabetes.”

Mouse studies

This work is based on human genome-wide studies where researchers found associations between certain DNA mutations and a person’s intake of specific macronutrients. Two of these mutations were located near the FGF21 gene, prompting the UI-led team to identify the role of this hormone in regulating macronutrient preference.

BonDurant and colleagues used genetically-engineered mouse models and pharmacological approaches to examine the role of FGF21 in regulating sugar cravings. In normal mice, BonDurant injected FGF21 and gave the mice a choice between a normal diet and a sugar-enriched diet. Researchers observed that the mice didn’t completely stop eating sugar, but ate seven times less than usual.

The research team also studied genetically-modified mice that either didn’t produce FGF21 at all or produced a lot of FGF21 (over 500 times more than normal mice). The genetically-modified mice had a choice between the same two diets as the normal mice. Researchers observed that the mice that didn’t produce FGF21 at all ate more sugar, while the mice that produced a lot of FGF21 ate less sugar.

Based on these results, the team concluded that FGF21 decreases appetite and intake of sugar. However, FGF21 does not reduce intake of all sugars (sucrose, fructose, and glucose) equally. FGF21 also doesn’t affect the intake of complex carbohydrates.

Neural pathways that suppress sugar intake

While BonDurant, a Dean’s Graduate Research Fellow and a UI Sloan Scholar, found that FGF21 sends signals to the brain, additional work is necessary to identify the neural pathways that regulate FGF21’s ability to manage macronutrient preference. UI researchers are focused on the hypothalamus—a section of the brain responsible for regulating feeding behavior and energy homeostasis.

“In addition to identifying these neural pathways, we would like to see if additional hormones exist to regulate appetite for specific macronutrients like fat and protein, comparable to the effects of FGF21 on carbohydrate intake,” Potthoff says. “If so, how do those signals intertwine to regulate the neural sensing of different macronutrients?”

In addition to Potthoff and BonDurant, the UI research team included Lila Peltekian, Meghan Naber, Terry Yin, Kristin Claflin, Martin Cassell, Anthony Thompson, Kamal Rahmouni, and Andrew Pieper.

The UI team collaborated with researchers from the University of Copenhagen and the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

The study was funded in part by grants from the American Diabetes Association, the National Institutes of Health, the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation, the University of Iowa Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research.