The sex of human and all mammalian babies may be determined by a simple modification of a virus that insinuated itself into the mammalian genome as recently as 1.5 million years ago, a new Yale University-led study has found.

“Basically, these viruses appear to allow the mammalian genome to continuously evolve, but they can also bring instability,” said Andrew Xiao of the Department of Genetics and Yale Stem Cell Center, senior author of the paper published online March 30 in the journal Nature. “Aside from the embryo, the only other places people have found this virus active is in tumors and neurons.”

Xiao and the Yale team discovered a novel mechanism by which the early embryo turns off this virus on the X chromosome, which ultimately determines the sex of an organism. If the level of this molecular marker is normal, X chromosomes remain active, and females and males will be born at an equal ratio. If this marker is overrepresented, X chromosomes will be silenced, and males will be born twice as often as females.

“Why mammalian sex ratios are determined by a remnant of ancient virus is a fascinating question,” Xiao said.

Tens of millions of years ago viruses invaded genomes and duplicated themselves within the DNA of their hosts. Xiao estimated that more than 40% of the human genome is made up of such remnants of viral duplications. In most cases, these remnants remain inactive, but recently scientists have discovered they sometimes take on surprising roles in developing embryos and may even push mammalian evolution. Researchers found that the virus active in the mouse genome that influences sex ratios is relatively recent — in evolutionary terms — and is enriched on the X chromosome.

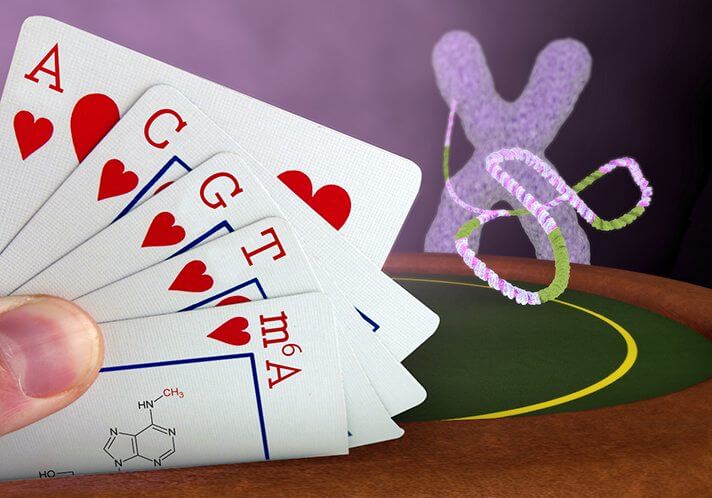

The Yale-led team found the mechanism that disables the virus. The newly discovered modification in mammals is a surprising expansion of the epigenetic toolbox, say the researchers. Epigenetics modulates gene expression during development without actually altering the sequences of genes. In the new marker, a methyl bond is added to adenine — one of the four nucleotides that comprise base pairs in DNA — allowing it to silence genes. For decades, most researchers assumed that a modification of the nucleotide cytosine was the only form of gene silencing in mammals.

Xiao said it is possible that this mechanism might be used to suppress cancer, which has been known to hijack the same virus to spread.

He also noted in other organisms, such as C elegans and the fruit fly Drosophila, this mechanism plays an entirely opposite role and activates genes, not suppresses them.

“Evolution often uses the same piece but for different purposes and that appears to be the case here,” Xiao said.

Tao P. Wu of Yale is the lead author of the study.

Pacific Biosciences of Menlo Park provided the technology used in the discovery.

Primary funding for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health.