Duke researchers have developed a system that allows real-time optical and electrical observations of the gut’s nervous system in a live animal.

And if you weren’t aware that the gut had its own nervous system, don’t worry, you’re not alone.

“The first time I ever heard of the enteric nervous system was two years ago, and I was like ‘What’s that?'” said Xiling Shen, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Duke University and author of the study appearing June 7, 2016 in Nature Communications. “Even with neurobiologists, their only exposure to it is typically something like a half-page in a textbook. But it’s actually very important.”

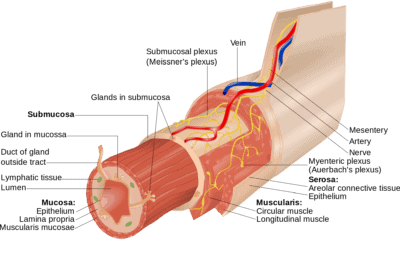

Consisting of five times more neurons than the spinal cord and often termed as a “second brain,” the enteric nervous system is a mesh-like sheath of neurons that controls the gastrointestinal tract. It regulates how food moves through the digestive system and communicates potential problems to the immune system. And while it has a direct line to both the brain and spinal cord, the enteric system has the ability to direct the organs under its control independent of either system.

Despite its importance, however, very little is known about the enteric nervous system, such as how it responds to medications or what can go wrong with it to cause disease.

“About one-quarter of the world’s population is affected by a functional gastrointestinal disorder,” Shen said. “You’ve probably heard of the term functional GI disorder, which encompasses diseases like irritable bowel syndrome, constipation and incontinence. If you look at the physiology in these diseases, the gut looks fine. It’s the nerves that are somehow malfunctioning. And the reason the term includes so many diseases is because we really don’t have any idea what’s going on with those nerves.”

Shen is looking to change that by literally installing an observation window.

In the new study, Shen implanted a transparent window made of tough borosilicate glass into the skin over the stomachs of mice. With no skull or bone structures to anchor the window, he needed to devise a 3D-printed surgical insert for stabilization. The device prevents the intestines from moving too much while maintaining normal digestive functions, allowing researchers to look at the same spot over multiple days.

Being the first to get a live look at the enteric nervous system, Shen was not about to waste the view. Because the gut can be a busy, noisy environment, he devised a system to record both electrical and optical activity at the same time — also a first for the field.

The experiment uses transgenic mice with nerves that light up with a green hue when firing. By using a transparent graphene sensor to obtain electrical signals from the nerves, Shen gained an unobstructed view of the neural activity.

The optical signal gives spatial resolution, allowing researchers to tell which neuron is firing. The electrical signal provides time resolution, which pins down the exact waveform of the firing neurons. Shen said the enteric nervous system is now ready to be explored.

“So much is known about the brain and spinal cord because we can open them up, look at them, record the neural activities and map their behaviors,” said Shen. “Now we can start doing the same for the gut. We can see how it reacts to different drugs, neurotransmitters or diseases. We have even artificially activated individual neurons in the gut with light, which nobody has ever done before. This innovation will help us understand this ‘dark’ nervous system that we currently have completely no idea about.”