In a creative stroke inspired by Hollywood wizardry, scientists from Harvard Medical School and Technion-Israel Institute of Technology have designed a simple way to observe how bacteria move as they become impervious to drugs.

The experiments, described in the Sept. 9 issue of Science, are thought to provide the first large-scale glimpse of the maneuvers of bacteria as they encounter increasingly higher doses of antibiotics and adapt to survive—and thrive—in them.

To do so, the team constructed a 2-by-4-foot petri dish and filled it with 14 liters of agar, a seaweed-derived jellylike substance commonly used in labs to nourish organisms as they grow.

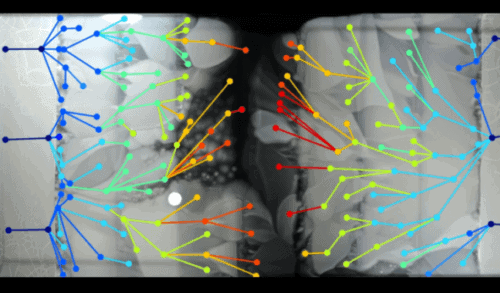

To observe how the bacterium Escherichia coli adapts to increasingly higher doses of antibiotics, researchers divided the dish into sections and saturated them with various doses of medication. The outermost rims of the dish were free of any drug. The next section contained a small amount of antibiotic—just above the minimum needed to kill the bacteria—and each subsequent section represented a 10-fold increase in dose, with the center of the dish containing 1,000 times as much antibiotic as the area with the lowest dose.

Over two weeks, a camera mounted on the ceiling above the dish took periodic snapshots that the researchers spliced into a time-lapsed montage. The result? A powerful, unvarnished visualization of bacterial movement, death and survival; evolution at work, visible to the naked eye.

The device, dubbed the Microbial Evolution and Growth Arena (MEGA) plate, represents a simple, and more realistic, platform to explore the interplay between space and evolutionary challenges that force organisms to change and adapt or die, the researchers said.

“We know quite a bit about the internal defense mechanisms bacteria use to evade antibiotics but we don’t really know much about their physical movements across space as they adapt to survive in different environments,” said study first author Michael Baym, a research fellow in systems biology at HMS.

The researchers caution that their giant petri dish is not intended to perfectly mirror how bacteria adapt and thrive in the real world and in hospital settings, but it does mimic more closely the real-world environments bacteria encounter than traditional lab cultures. This is because, the researchers say, in bacterial evolution, space, size and geography matter. Moving across environments with varying antibiotic strengths poses a different challenge for organisms than they face in traditional lab experiments that involve tiny plates with homogeneously mixed doses of drugs.

“It’s a powerful illustration of how easy it is for bacteria to become resistant to antibiotics” –Roy Kishony

A cinematic inspiration

The invention was borne out of pedagogical necessity—to teach evolution in a visually captivating way to students in a graduate course at HMS. The researchers adapted an idea from—of all places—Hollywood.

Senior study investigator Roy Kishony, of HMS and Technion, had seen a digital billboard advertising the 2011 film Contagion, a grim narrative about a deadly viral pandemic. The marketing tool was built using a giant lab dish to show hordes of painted, glowing microbes creeping slowly across a dark backdrop to spell out the title of the movie.

“This project was fun and joyful throughout,” Kishony said. “Seeing the bacteria spread for the first time was a thrill. Our MEGA-plate takes complex, often obscure, concepts in evolution, such as mutation selection, lineages, parallel evolution and clonal interference, and provides a visual seeing-is-believing demonstration of these otherwise vague ideas. It’s also a powerful illustration of how easy it is for bacteria to become resistant to antibiotics.”

Co-investigator Tami Lieberman says the images spark the curiosity of lay and professional viewers alike.

“This is a stunning demonstration of how quickly microbes evolve,” said Lieberman, who was a graduate student in the Kishony lab at the time of the research and is now a postdoctoral research fellow at MIT. “When shown the video, evolutionary biologists immediately recognize concepts they’ve thought about in the abstract, while nonspecialists immediately begin to ask really good questions.”

Bacteria on the move

Beyond providing a telegenic way to show evolution, the device yielded some key insights about the behavior of bacteria exposed to increasing doses of a drug. Some of them are:

- Bacteria spread until they reached a concentration (antibiotic dose) in which they could no longer grow.

- At each concentration level, a small group of bacteria adapted and survived. Resistance occurred through the successive accumulation of genetic changes. As drug-resistant mutants arose, their descendants migrated to areas of higher antibiotic concentration. Multiple lineages of mutants competed for the same space. The winning strains progressed to the area with the higher drug dose, until they reached a drug concentration at which they could not survive.

- Progressing sequentially through increasingly higher doses of antibiotic, low-resistance mutants gave rise to moderately resistant mutants, eventually spawning highly resistant strains able to fend off the highest doses of antibiotic.

- Ultimately, in a dramatic demonstration of acquired drug resistance, bacteria spread to the highest drug concentration. In the span of 10 days, bacteria produced mutant strains capable of surviving a dose of the antibiotic trimethoprim 1,000 times higher than the one that killed their progenitors. When researchers used another antibiotic—ciprofloxacin—bacteria developed 100,000-fold resistance to the initial dose.

- Initial mutations led to slower growth—a finding that suggests bacteria adapting to the antibiotic aren’t able to grow at optimal speed while developing mutations. Once fully resistant, such bacteria regained normal growth rates.

- The fittest, most resistant mutants were not always the fastest. They sometimes stayed behind weaker strains that braved the frontlines of higher antibiotic doses.

The classic assumption has been that mutants that survive the highest concentration are the most resistant, but the team’s observations suggest otherwise.

“What we saw suggests that evolution is not always led by the most resistant mutants,” Baym said. “Sometimes it favors the first to get there. The strongest mutants are, in fact, often moving behind more vulnerable strains. Who gets there first may be predicated on proximity rather than mutation strength.”

Co-investigators included Eric Kelsic, Remy Chait, Rotem Gross and Idan Yelin.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant R01-GM081617 and by the European Research Council FP7 ERC Grant 281891.