Gun violence is often described as an epidemic or a public health concern, due to its alarmingly high levels in certain populations in the United States. It most often occurs within socially and economically disadvantaged minority urban communities, where rates of gun violence far exceed the national average. A new Yale study has established a model to predict how “contagious” the epidemic really is.

In a study published online on Jan. 3 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the researchers studied the probability of an individual becoming the victim of gun violence using an epidemiological approach.

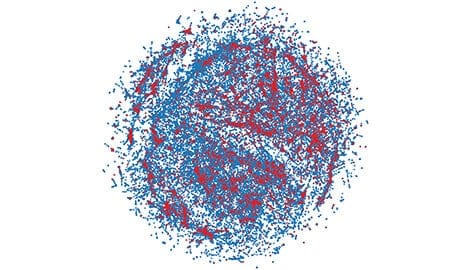

Led by Andrew Papachristos, associate professor of sociology at Yale, the researchers analyzed a social network of individuals who were arrested during an 8-year period in Chicago, Illinois — a city that has rates of gun violence more than three times the national average. The team studied connections between people who were arrested together for the same offense, and found that more than 60% of all gun violence during this time period happened in “cascades” — or connected chains — through these particular social networks.

“We want to take this epidemic of gun violence out of the criminal justice paradigm and put it in a public health context that focuses on victims and the reduction of trauma,” says Papachristos, corresponding author on the study.

The study also determined that an individual within these social networks was at the greatest risk of being shot within a period of about 125 days after their “infector,” the person most responsible for exposing the subject to gun violence, was the subject of gun violence. These results provide evidence that gun violence is not just an epidemic, but it has specific network patterns that might provide plausible opportunities for interventions, notes Papachristos. “There is a real value in understanding the timing of these events as a way to identify victims, and where we can insert resources such as violence- and harm-reduction programs into these networks.”

“If we want to drop gun violence rates in this country, we have to care about the young men with criminal records who become victims of gun violence,” says Papachristos. “By and large these are young men of color who have criminal records. Their lives are worth saving.”

Other authors on the study included Ben Green ’14 and Thibaut Horel from Harvard University.

Due to the fact that human social structures seem to be limited by Dunbar’s Number (around 150), with deeper familial affect including yet a smaller number perhaps 20-30 maximum (these numbers have very good evolutionary value, as habitats cannot support larger quantities of the species, leading to what we might see as valuable evolved constraints on group size), our desire for group inclusion/acceptance is a profound motivator.

Without going into the structural differences in our brains from other animals, we do know that we have deep emotional roots for both normative acquiescence, and extreme willingness to submit to normative pressures.

Solomon Asch’s experiments back in 1951 showed that truth is not the major factor in our decisions, when compared with this felt need to be perceived as part of an ingroup. Stanley Milgram’s looks at the mild coercion occurring through appearance of authority are also relevant. That period of experiment occurred in a spirit of questioning why extreme political violence could be perpetrated. The more recent questioning of self-selection as authority vs. victim relating to Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment may help open up social science inquiry, but, as will be seen, a y real understanding necessitates a broader familiarity with many disciplines.

Moreover concerning adaptive social behaviors run awry in large, changing populations, all our psychological biases and heuristics kick in with a vengeance above about Dunbar’s Number: we begin to stereotype and overgeneralize about others and their beliefs and relationships.

Although we use cues we call racial or cultural, the seemingly unavoidable mechanisms that cause us to outgroup others have that extremely valid evolutionary value of causing group fragmentation and dispersal.

There have been some dangerously maladaptive dimensions to humans clustering in large, anonymous, saturated habitats, and internecine violence is one. While we may violently fragment from our cousins, only eager to meet when our local niches are not threatened (considerable experiment has been done on the increased attractiveness of those genetically more distant from oneself), the nature of the mentioned cognitive heuristics and biases prevent us from successfully becoming what we attempt since the rise of agricultural city-states.

Brain size and hierarcical submission arose when groups exceeded those sizes I mentioned. Certainly connsensus id profoundly diminished, and the use of violence vastly increases.

So, perceived membership in a firearm-using group would tend to promote the use of this weaponry to resolve ever-smaller disputes, as we feel more threatened by strangers and outgroups.

Other maladaptations occur. We behave situationally, each individual holding capacity for alternative responses, with our social brains sometimes working overtime evaluating perceived reciprocity, deception, and detection of deception.

These capacities do involve our stress response, and thus we can prize relief from that stress beyond the lives of others (and sometimes our own self).

Quick relief is only a two-pound squeeze of a trigger away.

In short, humans do not have the social capacity to possess firearms, which depersonalize the imposition of death upon other organisms, and have extremely stable evolved characteristics which may prevent our becoming as eusocial as the present, certainly since humans occupied habitats to what ecologists and population biologists call “carrying capacity.

Intraspecies social carrying capacity has not yet been studied extensively to my knowledge in light of the evolved psychological constraints mentioned.

Considerable background in emerging understanding of brain structure and function (largely in the last decade or so), epigenetics of behavior, psychological issues, evolution, and anthropological understanding of social patterns are required to grasp the issue fully enough to discuss the viability of firearm possession in overdense and increasing human overpopulation.

Social breakdown occurs in laboratory experiments with social animals, in various ways, most of which, maladaptive for individuals, is a very likely adaptive mechanism for the species. It has so far been politically incorrect to the point of anathema to explore certain sexual and violence response through epigenetic mediation; this is in part a result of that vague overgeneralization that has previously led to religious belief, which fantasy has been adaptive for certain groups in our long history of having saturated most of the earth’s productive ecosystems.

These issues are very clear to those educated in and keeping up with biological and behavioral sciences, but funding for working with the very obvious hypotheses has been absent, as few professionals wish to endanger their career in the coercive religiopolitical climate.

Young irresponsible women having babies is the root cause.