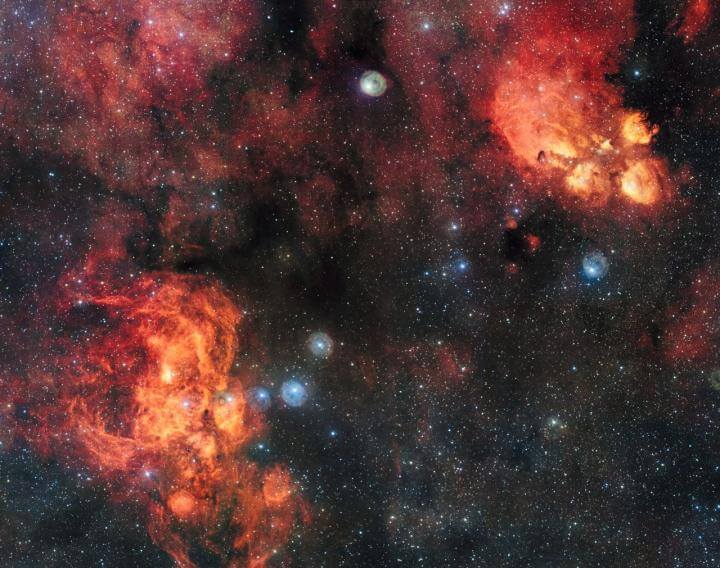

NGC 6334 is located about 5500 light-years away from Earth, while NGC 6357 is more remote, at a distance of 8000 light-years. Both are in the constellation of Scorpius (The Scorpion), near the tip of its stinging tail.

The British scientist John Herschel first saw traces of the two objects, on consecutive nights in June 1837, during his three-year expedition to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. At the time, the limited telescopic power available to Herschel, who was observing visually, only allowed him to document the brightest “toepad” of the Cat’s Paw Nebula. It was to be many decades before the true shapes of the nebulae became apparent in photographs — and their popular names coined.

The three toepads visible to modern telescopes, as well as the claw-like regions in the nearby Lobster Nebula, are actually regions of gas — predominantly hydrogen — energised by the light of brilliant newborn stars. With masses around 10 times that of the Sun, these hot stars radiate intense ultraviolet light. When this light encounters hydrogen atoms still lingering in the stellar nursery that produced the stars, the atoms become ionised. Accordingly, the vast, cloud-like objects that glow with this light from hydrogen (and other) atoms are known as emission nebulae.

The three toepads visible to modern telescopes, as well as the claw-like regions in the nearby Lobster Nebula, are actually regions of gas — predominantly hydrogen — energised by the light of brilliant newborn stars. With masses around 10 times that of the Sun, these hot stars radiate intense ultraviolet light. When this light encounters hydrogen atoms still lingering in the stellar nursery that produced the stars, the atoms become ionised. Accordingly, the vast, cloud-like objects that glow with this light from hydrogen (and other) atoms are known as emission nebulae.

Thanks to the power of the 256-megapixel OmegaCAM camera, this new Very Large Telescope Survey Telescope (VST) image reveals tendrils of light-obscuring dust rippling throughout the two nebulae. At 49511 x 39136 pixels this is one of the largest images ever released by ESO.

OmegaCAM is a successor to ESO’s celebrated Wide Field Imager (WFI), currently installed at the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope on La Silla. The WFI was used to photograph the Cat’s Paw Nebula in 2010, also in visible light but with a filter that allowed the glow of hydrogen to shine through more clearly (eso1003). Meanwhile, ESO’s Very Large Telescope has taken a deep look into the Lobster Nebula, capturing the many hot, bright stars that influence the object’s colour and shape (eso1226).

Despite the cutting-edge instruments used to observe these phenomena, the dust in these nebulae is so thick that much of their content remains hidden to us. The Cat’s Paw Nebula is one of the most active stellar nurseries in the night sky, nurturing thousands of young, hot stars whose visible light is unable to reach us. However, by observing at infrared wavelengths, telescopes such as ESO’s VISTA can peer through the dust and reveal the star formation activity within.

Viewing nebulae in different wavelengths (colours) of light gives rise to different visual comparisons on the part of human observers. When seen in longer wavelength infrared light, for example, one portion of NGC 6357 resembles a dove, and the other a skull; it has therefore acquired the additional name of the War and Peace Nebula.